News

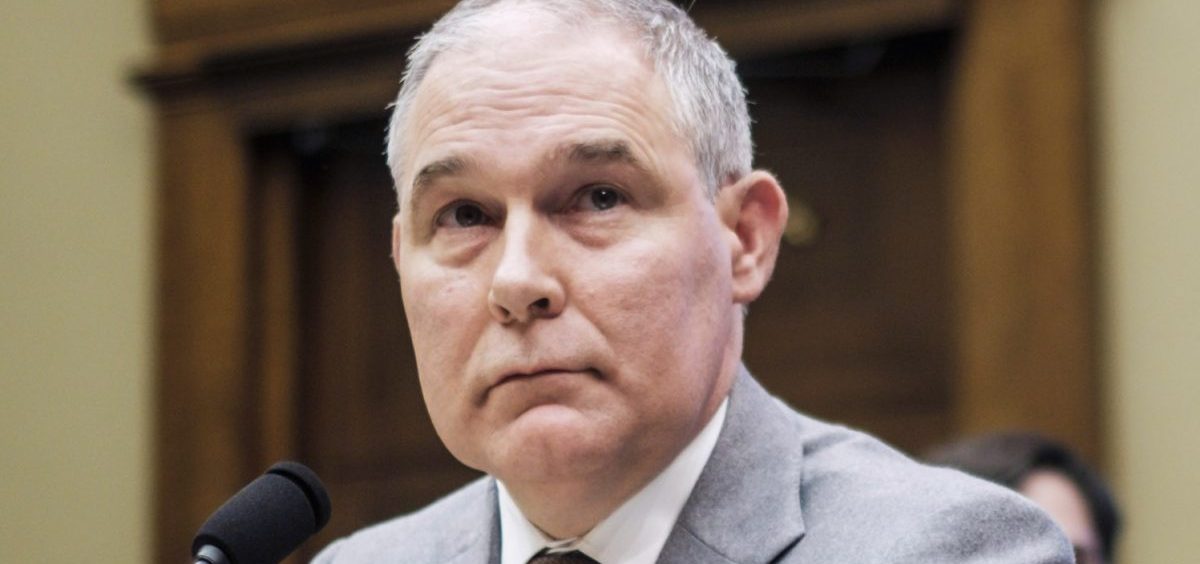

Scott Pruitt Out At EPA

By: Rebecca Hersher | Brett Neely | NPR

Posted on:

Scott Pruitt will no longer lead the Environmental Protection Agency, President Trump announced Thursday afternoon via Twitter.

Pruitt was among the most controversial of President Trump’s original Cabinet-level picks. He embodied the administration’s broad support for the fossil fuel industry and its disdain for climate science, and attracted the attention of Congress and the EPA’s inspector general for a wide range of potential ethics violations that hinged on misusing his power and spending far more taxpayer money than his predecessors had on travel and security expenses.

As investigations piled up, multiple close aides and EPA staffers resigned from the agency, and support among congressional Republicans slowly weakened.

Pruitt came to the EPA from Oklahoma, where he spent years as the state’s attorney general attacking the federal agency he would eventually run. With other Republican attorneys general, he sued the EPA to stop ozone and methane emissions rules and block regulations on coal-fired power plants. Throughout his career, he has publicly questioned climate change and whether it is caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Until a replacement for Pruitt is named, the EPA will be led by Deputy Administrator Andrew Wheeler, himself a former coal lobbyist and senior Senate staffer.

Ethics questions and investigations

While Pruitt’s environmental policies were controversial, it was his spending and attempts to use the position for personal gain that resulted in more than a dozen investigations.

Several patterns were quickly established, including unusually high spending on his office and travel and continually mixing his personal and professional lives.

The EPA spent about $43,000 on a soundproof phone booth for the administrator’s office, and The Washington Post reported that Pruitt spent thousands of dollars on first-class plane tickets. The New York Times reported Pruitt’s chief of security proposed that Pruitt spend $70,000 on two desks, one of them bulletproof. The desks were not purchased.

Pruitt cited security threats as one reason for the first-class travel, and he spent tens of thousands of dollars on a publicly-funded, 24-hour security detail, which his office said was necessary to protect him from threats. Pruitt’s security detail reportedly accompanied him on personal trips, including a family vacation to Disneyland. In August 2017, the EPA’s Office of the Inspector General began investigating Pruitt’s travel and security expenses and has widened the investigation multiple times.

Pruitt aides also sought to protect their boss from questions, and help his wife pursue business deals, according to New York Times and Washington Post analyses of thousands of internal emails released to the Sierra Club under the Freedom of Information Act.

According to CNN, Pruitt broke with a tradition set by past EPA administrators and kept a secret, non-public calendar to hide meetings with industry representatives and controversial figures. At public appearances, EPA staff often told reporters and citizens that the administrator would only answer pre-planned questions, the Times reported.

Chick-fil-A, industry lobbyists

In May 2017, a scheduler for Pruitt reached out to the chief executive of the restaurant chain Chik-fil-A about setting up a meeting to discuss a “potential business opportunity,” the Post reported. Another EPA official reached out on Pruitt’s behalf to conservative political groups to ask about potential job opportunities for Pruitt’s wife, Marlyn Pruitt, who eventually landed a temporary position as an independent contractor for a conservative advocacy group.

In April, the Office of Government Ethics published a letter in which acting director and general counsel David Apol wrote some of Pruitt’s actions, including the use of his subordinates’ time, “do raise concerns about whether the Administrator is using public office for personal gain in violation of ethics rules” and “raise concerns about whether the Administrator misused his position.”

As administrator, Pruitt also maintained close relationships with energy industry lobbyists and executives. He rented a room in a Washington, D.C., condominium owned by the wife of a prominent lobbyist, J. Steven Hart, who personally represented, among others, a liquefied natural gas company that stands to profit from Pruitt’s push to increase American gas exports, The Daily Beast reported. Hart also represented other companies with business before the EPA.

In an interview on Fox News, Pruitt incorrectly stated, “Mr. Hart has no clients that have business before this agency.”

Under the rental agreement, Pruitt paid $50 for each night he spent at the condo, which Pruitt described as “like an Airbnb situation.” In an initial statement, an EPA lawyer defended the lease agreement, saying it was “consistent with federal ethics regulations regarding gifts” but noted later in a memo obtained by CNN that he had not reviewed whether Pruitt was adhering to the lease’s terms after an ABC News report that his daughter may have stayed in another room at the condo.

Pruitt also came under fire for enriching political appointees at the agency. The Atlantic reported that in March, Pruitt circumvented the normal bureaucratic process to approve substantial pay increases for two EPA staffers after the White House refused to sign off on the raises. Both aides later resigned. One later told House investigators that she was routinely asked to do personal tasks for Pruitt, including one instance in which she called the Trump Hotel in Washington, D.C. to ask about purchasing a used mattress.

Pruitt said he did not know about the salary increases until after they were granted, although in later congressional testimony he said he knew they were happening but not the amounts. He used the same provision to hire Nancy Beck, a longtime executive at the largest U.S. chemical industry lobbying group, to oversee toxic chemical regulation for the EPA. Earlier this year, the EPA inspector general announced it was auditing Pruitt’s use of so-called administratively determined positions.

Trump support

As Pruitt’s ethical problems deepened, he lost support from congressional Republicans and influential conservatives.

As reports of Pruitt’s conduct continually surfaced, Republican senators grew weary of defending him, saying they agreed with his policies but not his conduct.

“He is acting like a moron and he needs to stop it,” said Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., on CNN.

Pruitt is “about as swampy as you get here,” said Sen. Joni Ernst, R-Iowa, who also said Pruitt was insufficiently supportive of ethanol fuel, a major industry in Iowa.

Prominent conservative talk show host Laura Ingraham repeatedly called for Pruitt’s firing. “It just doesn’t look good. If you want to drain the swamp, you got to have people in it who forego personal benefits and don’t send your aides around doing personal errands on the taxpayer dime, otherwise you make everyone else look bad,” said Ingraham on her radio show in June.

Although multiple White House staff reportedly asked President Trump to remove Pruitt, the EPA chief was able to hold on in part because he built a strong rapport with the president over their shared dislike of the media.

“Scott Pruitt is doing a great job within the walls of the EPA. I mean, we’re setting records,” said Trump in June. “Outside, he’s being attacked very viciously by the press. And I’m not saying that he’s blameless, but we’ll see what happens.”

Deregulatory agenda

As head of the EPA, Pruitt focused on taking the agency “back to basics,” which he described as clean air and clean water policies, and asking state and local governments to take more responsibility for enforcing environmental regulations. He worked with the White House to undercut or begin rolling back many of the Obama administration’s signature environmental policies, including leaving the Paris climate accord, reversing a sweeping rule that designated which bodies of water are subject to federal authority, and moving to repeal the Clean Power Plan regulation of carbon dioxide emissions. During his tenure, many climate change documents and pages were removed from the agency’s website.

Pruitt also created a task force to expedite cleanup plans for some of the most contaminated sites in the country, a move that was cautiously supported by environmental groups frustrated by understaffing of the Superfund program under previous administrations. However, the task force proved to be opaque about its decision-making process, and Pruitt did not allocate additional funds to the program. This spring, the man in charge of overseeing Superfund cleanups abruptly stepped down.

The EPA also said it would weaken fleet-wide fuel economy standards, rolling back Obama-era limits meant to nearly double the average fuel economy for cars and SUVs to more than 50 miles per gallon by 2025. “I am determining that those standards are inappropriate and should be revised,” Pruitt announced, flanked by leaders of three auto industry trade groups at a press conference. “I just want to say first and foremost to you in the auto sector. Thank you for your leadership. Thank you for the difference you’ve made on behalf of the environment.”

California is leading a coalition of 17 states suing the EPA over the planned change in efficiency standards, arguing that a weakened rule would violate the Clean Air Act. Automobile emissions and transportation currently account for more than a quarter of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))