Culture

Looking Back at Woodstock, 50 Years On

By: Emily Votaw

Posted on:

In 1969, the first man landed on the moon just a month after the Stonewall Riots in Greenwich Village ignited the fight for LGBT rights in the U.S. All over the country, the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements were in full swing, eking out equality for women and people of color while public resistance against the Vietnam War was mounting as the number of troops lost to the conflict continued to escalate.

Also, in August of 1969, recent high school graduate Wendy McVicker was in a carful of male co-workers headed to White Lake, NY, for a music festival taking place on a 600-acre dairy farm. The gathering would go on to be known as Woodstock ’69 – an iconic event that celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

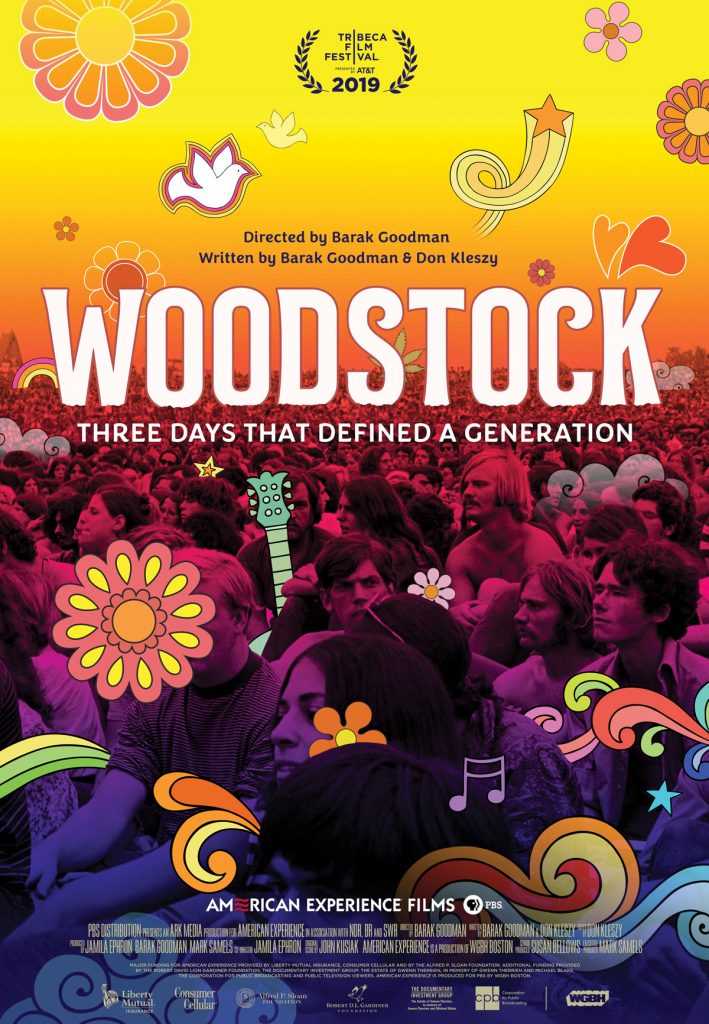

On Tuesday, August 6 at 9 p.m. EDT, WOUB-TV will broadcast filmmaker Barak Goodman’s Woodstock: Three Days that Defined a Generation, a documentary that examines those three days that cemented a cultural revolution amidst significant political and social unrest, forever changing the status quo not only for the half million people in attendance at the event but for the country – and world, at large. There will be an encore broadcast of the documentary on Saturday, August 17.

McVicker’s group was traveling from a suburb of Philadelphia where they worked at an upscale design store: McVicker in the sales of china, jewelry, furniture, and more; and her co-workers in the delivery of such high-end goods.

“At the time, the other sales people I was working with were all older than me, and very preoccupied with marriage and social standing,” McVicker said. “I was very good at sales, but there was a point at which I realized that selling $350 plexiglass clocks didn’t seem to have the deepest purpose for my life.”

Although McVicker had that revelation entirely of her own volition, the experience of the festival that she and her co-workers were heading to would solidify that sentiment to McVicker, who would go on to pursue a fruitful career in literature rather than sales.

“(Woodstock) was billed as music and art fair, and that I had never heard of before, and I knew it was an important thing to be a part of. It was a very different setting than what I was living in at work and it was glorious!” said McVicker, whose group, like many other attendees, faced difficulty making it out to the rural farm. “I seem to remember we drove in and eventually we had to park the car and walk the rest of the way and put up the tent and go to the hillside where the big stage was.”

Woodstock was planned by four very young men: concert promoter Michael Lang, music promoter Artie Kornfield, and venture capitalists Joel Rosenman and John P. Roberts. They had sketched out the event as a three-day music and art festival for 200,000 people August 15-18, 1969. They would have members of the Merry Pranksters-affiliated California-based commune The Hog Farm provide security – with their non-intrusive “Please Force,” asking attendees to “please not do that, do this instead.” They would hold the festival against the pastoral backdrop of Max Yasgur’s sprawling, tucked away upstate New York farm. Most importantly, they would feature incredible music.

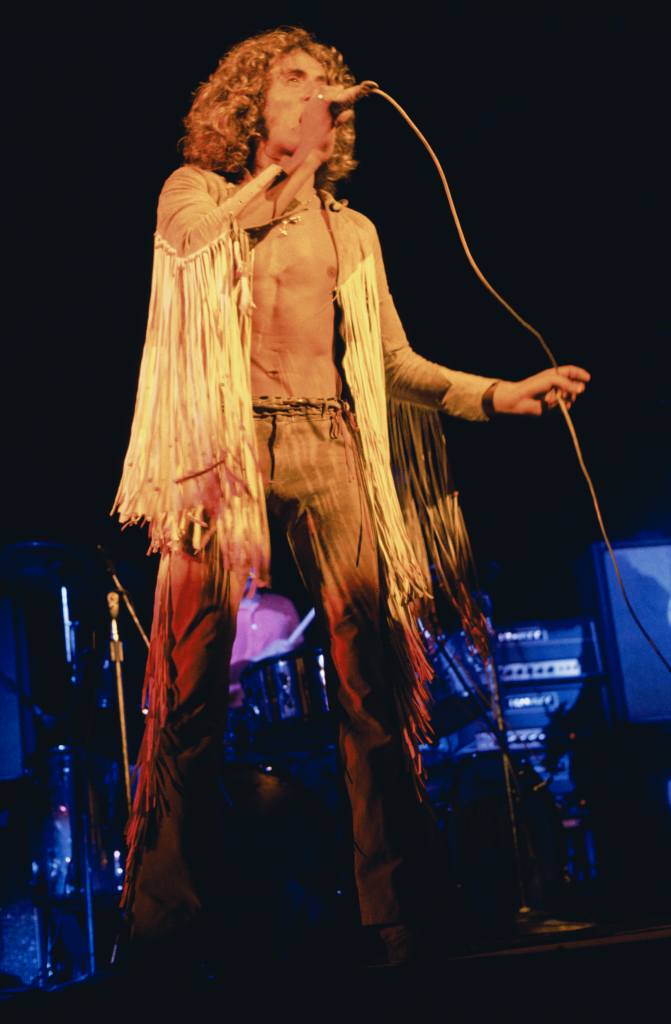

The festival starred a line-up of musicians who would go on to be cultural icons, in no small part due to their legendary performances at Woodstock. These included Joan Baez, Ravi Shankar, Arlo Guthrie, Country Joe and the Fish, Canned Heat, The Incredible String Band, Janis Joplin, the Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Sly and the Family Stone, The Who, Jefferson Airplane, The Band, Jimi Hendrix, and, somehow, many more.

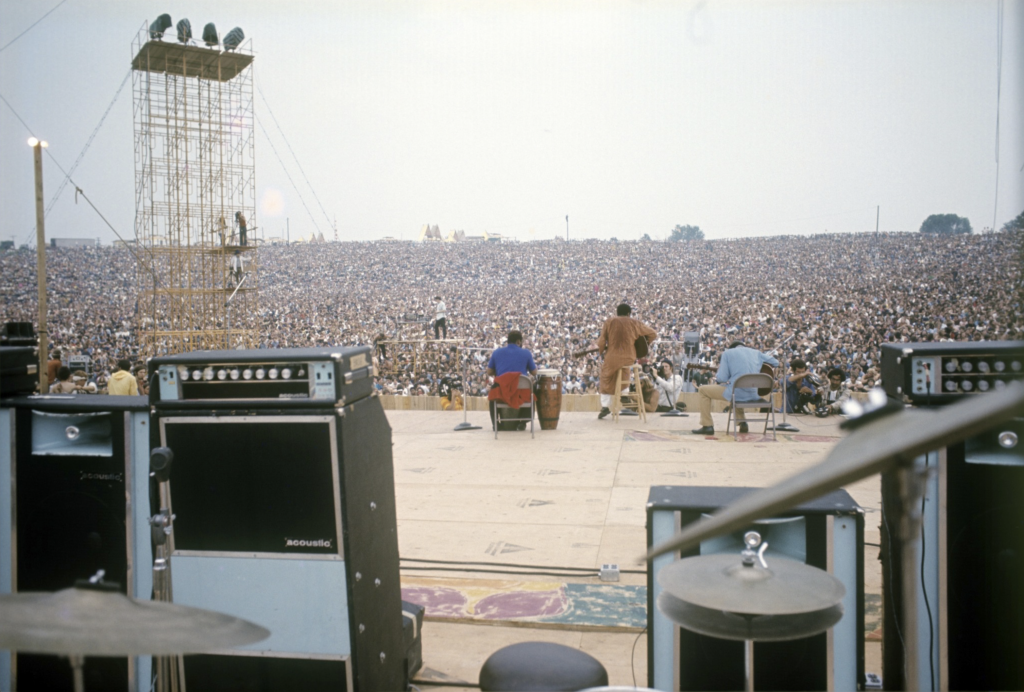

Even though on paper the event seemed nothing short of an idyllic hippie dream, the main issue with the event was one none of the promoters anticipated: that dream attracted more than 400,000 people.

Adequate food and sanitation became issues early on. The young promoters couldn’t convince any mainstream vendors that the event was worth their time and money, so, out of desperation, they hired three young men with little experience in the food service industry to open a concession stand, Food for Love, on the grounds of the festival. By Saturday night attendees had literally torched the stand in response to its long lines and exorbitant prices.

Hugh Romney, aka Wavy Gravy, perhaps the most famous member of The Hog Farm, told audiences Sunday morning from the main stage that “There’s a guy up there—some hamburger guy—that had his stand burned down last night. But he’s still got a little stuff left, and for you people that still believe capitalism isn’t that weird, you might help him out and buy a couple hamburgers.” This comment perhaps illustrates the ferocious pushback against the status quo that many of the attendees felt – this was supposed to be a countercultural celebration, how dare someone try to cheapen it by charging for tickets or hot dogs!

John Borchard, an Athens-based musician and lifetime Athens resident, managed to wrangle tickets and a ride to the festival, only not to go. He also managed to accurately predict the aforementioned food and sanitation issues that would plague the festival — issues that were so bad that by the second day of the event, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller was considering sending 10,000 National Guard troops to disrupt the event. John Roberts dissuaded him of this, but the state did declare a state of emergency due to the festival.

“I had some real hesitations about going at all, just thinking about the issue in terms of the sheer volume of people who were going to be there,” said Borchard, who elected to wait and try to catch some of the enormous acts playing at the festival at other, more personal venues. “I knew the area, and I figured the only way you’d get out there is if you left a week before and camped out for a week or more.”

For some, like McVicker, the food situation wasn’t much of an issue at all.

“We were all privileged kids, I didn’t know anyone there who was risking starvation after not eating as much as usual for a few days. There was all that wonderful music and community to feed on!” she said. “And I, personally, after one experience with the porta-potty, decided that I did not want much to eat or drink because I did not want to go back there. The first time in that horrible, dark, smelly closet, I thought to myself ‘I’m going to stop the cycle, if nothing much goes in, nothing much has to go out.’”

Ultimately the people of surrounding Sullivan County heard of the food shortages at the festival and gathered thousands of food donations to be airlifted to the site, and the Hog Farm established a free kitchen that fed people vegetables, granola and brown rice. By Sunday, some people who didn’t want to lose their spot near the stage hadn’t eaten in days – so organizers passed out cups of granola from the stage to the hungry masses that morning.

Even with the less than ideal conditions: the rain that came on Saturday, the woeful lack of adequate porta potties or food options, there were only two deaths at Woodstock: one related to insulin usage and another involving a sleeping concert goer being run over by a tractor. All in all, half a million young people – most of which were muddy, hungry, and dehydrated; and many of which were also tripping on all types of incredibly strong psychedelics for a good portion of the festival, managed to manifest a real sense of unity, one that came to symbolize the generation’s autonomy, strength, and the importance of a devotion to nonconformity.

“We were all privileged kids. When I watched the film (Michael Wadleigh’s 1970 Woodstock documentary,) I really realized it was mostly a bunch of white kids at Woodstock partying on a hill, probably from the suburbs. Those who had been able to come up with the money for a ticket and had the means to get way out there in the country,” said McVicker. “So, living in Athens, where we see fests all the time, privileged white kids partying, I realized, ‘Oh no, the people who lived in the community of White Lake, NY probably saw us the same way.’ But we did feel like we were part of a movement. It was also billed as an “Aquarian Exposition,” ushering in the Age of Aquarius, when all was going to be peace and love. I don’t know how many people actually believed that, but you hope that in youth you can feel optimism and excitement about the future. When we are young, we’re full of energy ourselves, and goodwill, and we think, ‘we can fix those flaws!’ Takes a while before you think, ‘maybe they come with the world, I don’t know.’”

Borchard said that he feels that Woodstock, or maybe more broadly, 1969, marked a time in which a great portion of his generation realized their autonomy.

“In 1970, we had the Kent State shootings, which were really shocking. I think you can look at an event like that as the other side of that era. That’s when our generation, or at least me, realized that we had to make some real decisions about what we were going to do,” he said. “I remember I was driving down Congress Street in front of Bromley Hall when I heard about Ken State on my car radio. And I went, ‘I either need to get a gun or I need to think about moving to Canada,’ because it was clear that there was a concerted effort to really oppress public speech, public opinion, and demonstrations. It was really sobering in a way that was much more concrete than Woodstock was, but I think Woodstock was sort of the first, at least for me and a lot of my friends, inkling that we had some real power.”

“But we did feel like we were part of a movement. It was also billed as an “Aquarian Exposition,” ushering in the Age of Aquarius, when all was going to be peace and love. I don’t know how many people actually believed that, but you hope that in youth you can feel optimism and excitement about the future. When we are young, we’re full of energy ourselves, and goodwill, and we think, ‘we can fix those flaws!’ Takes a while before you think, ‘maybe they come with the world, I don’t know.’” – Wendy McVicker

“As every generation does, we got to that point where we had to look at our parents’ and our communities’ values and we had to make some decisions about those values. I think our generation really, whether you’re talking about the civil rights movement or the women’s movement, or the LGBT movements, all of those social changes really came about during and to large extent because of the efforts of our generation,” said Borchard. “We saw a lot of things that were really didn’t jive with what we’d been taught in school about the American dream and the American value system. People said, ‘Well, we’re going to make some changes and make sure that there is equality for everyone. That there is some real freedom. That you don’t have to be a slave somewhere to corporation, that there are other ways of making your way in the world and making a living.’ I think that was a lot of that really crystallized, or at least began to crystallize during and after Woodstock happened.”

For McVicker, one of the more abstract sensations about the festival was being a young woman without ready access to a mirror for three days.

“I know at that time that I was extremely self-conscious about how I looked, and I worried about it. I examined my image in the mirror, probably many, many times a day. And all of a sudden, there were no mirrors,” she said. “It felt like the image of myself that was always interposed between me and whoever I was looking at disappeared in the experience of there being no mirrors. I just felt that I was seeing people more clearly. That was a really good feeling.”

“We saw a lot of things that were really didn’t jive with what we’d been taught in school about the American dream and the American value system. People said, ‘Well, we’re going to make some changes and make sure that there is equality for everyone. That there is some real freedom. That you don’t have to be a slave somewhere to corporation, that there are other ways of making your way in the world and making a living.’ I think that was a lot of that really crystallized, or at least began to crystallize during and after Woodstock happened.” – John Borchard

This sensation solidified when she and her friends left the farm and started their journey back to Philadelphia.

“When we came out, we stopped at a roadside diner to get something to eat after not having ate much all weekend, and to use an actual restroom, and people turned around and sort of starred at us with alarm,” McVicker said. “Then I went into the restroom and I saw myself in the mirror and I thought, ‘no wonder!’ Wild haired and sunburned, I think we probably did look like we’d been through something and had just emerged.”