News

How Should Opioid Lawsuit Money Be Spent? Ohio Valley Has No Shortage Of Needs

By: Aaron Payne | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

At a town hall event in Logan, Ohio, Kelly Taulbee walks through the steps of an encounter with someone experiencing an opioid overdose. She’s training a group to use NARCAN, the opioid reversal medication. She pulled out the small applicator and demonstrated how easy it is to spray the medication in someone’s nose.

As the director of nursing for the Hocking County health department, she understands the importance of this life-saving medicine.

“It is simple. It is safe. It is effective,” she said.

But she also knows that NARCAN is just one of many tools needed to respond to a crisis that has grown to affect nearly every aspect of life in this rural corner of southern Ohio.

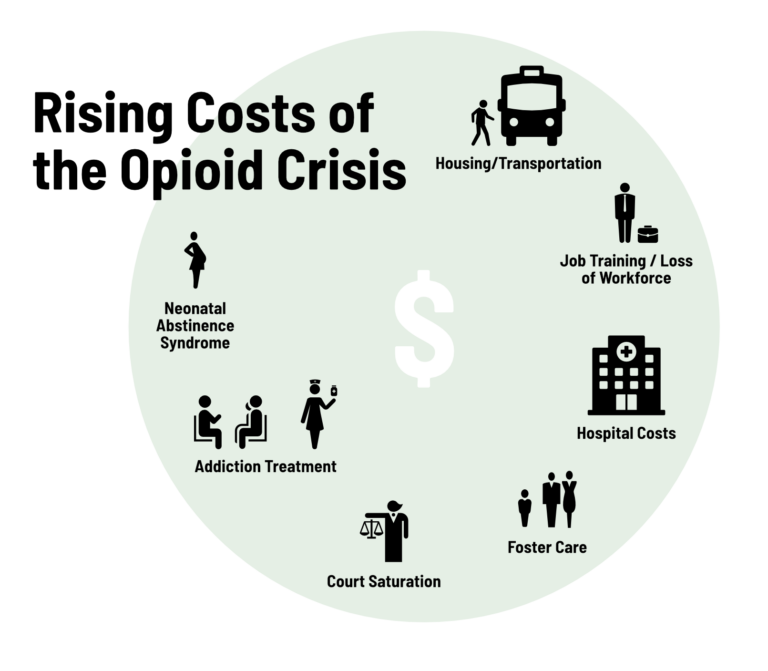

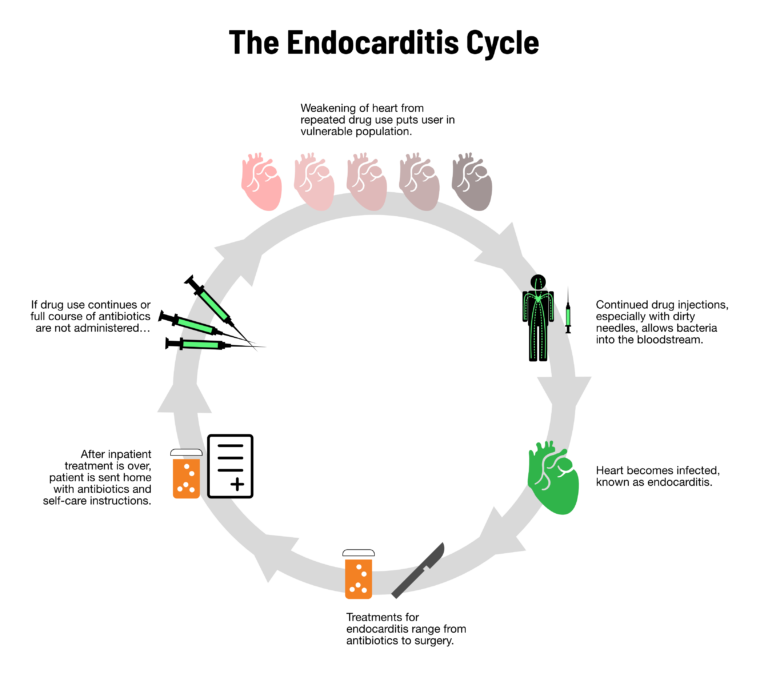

Communities need more treatment and recovery programs, more help for affected children and families, and housing and workforce training for those in recovery. Public health workers, on top of addressing addiction, are also dealing with diseases related to needle drug use such as HIV, Hepatitis C, and heart infections known as endocarditis.

All those efforts take money.

Taulbee would like to see more go toward treatment, especially in Hocking County.

“We do not have a detox center, she said. “We do not have a rehabilitation center. We have tons of agencies that are wanting to help people. But treatment, we need help with treatment.”

The first major federal case against opioid makers and distributors resulted in a $260 million settlement announced Monday in an Ohio courtroom. Master settlement talks have intensified as the trial date approaches for more than 2,000 lawsuits that are part of the consolidated National Prescription Opiate Litigation.

State, county and local governments are waiting to see how much money they’ll receive, if any, from a settlement or judgment, and they are weighing in on how money from these cases should be used.

Rural Challenges

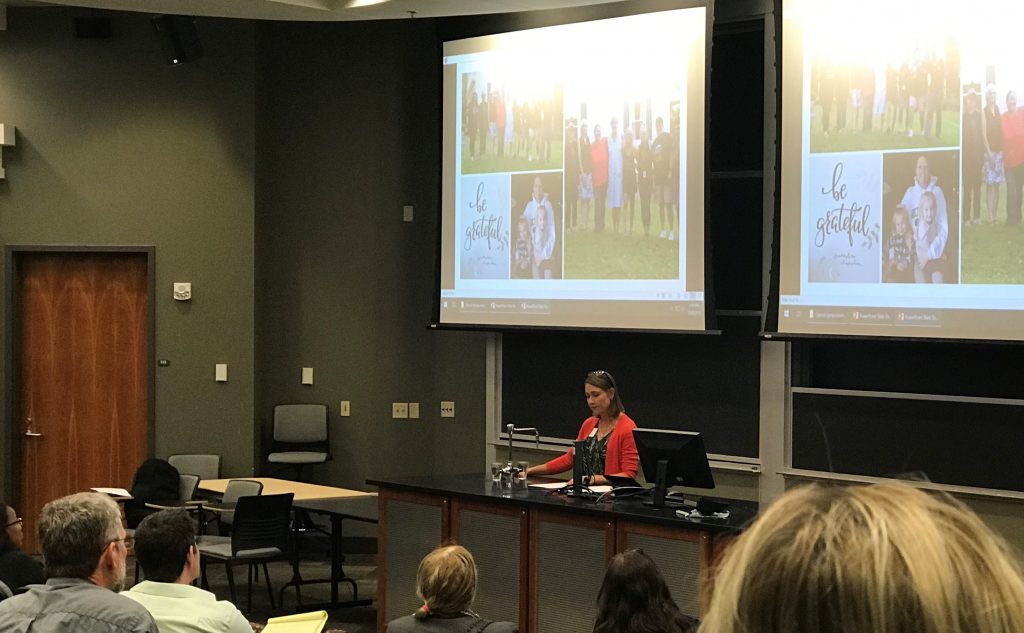

At a recent Ohio University symposium for solutions to the opioid epidemic, Betsy Anderson spoke about the importance of recovery housing.

She’s the executive director of Serenity Grove in Athens, Ohio. It houses five women as they begin their addiction recovery.

“Not just housing, but affordable, safe housing,” she said. “What’s affordable now is often in environments that are not so supportive and conducive to long-term recovery.”

Serenity Grove also helps these women get to appointments important to their recovery, like jobs or counseling services.

Transportation is a special challenge for rural areas that could use funding, as well.

“We have a grant-funded vehicle, but getting five different women to five different schedules every day is difficult,” Anderson said. “The women themselves are either not able financially to buy a car or don’t have driver’s licenses. Even if they were able to purchase a car, they encounter a lot of costs that can quickly take away from its ability to be an asset.”

Widespread Costs

Former Ohio Gov. John Kasich has teamed up with West Virginia University President Gordon Gee to present their plan for funding. Kasich and Gee formed Citizens for Effective Opioid Treatment, a nonprofit organization that hopes to guide money from a master settlement or judgment to hospitals.

Gee claims hospitals like those at West Virginia University have taken a hit from the opioid epidemic.

“We see this everyday,” he said. “The cost to the institutions is very large, but the cost in terms of what is happening to families and young people is really the issue we’re concerned about.”

The most tangible cost hospitals face related to the opioid epidemic is uncompensated care.

The American Hospital Association said hospitals “of all types have provided more than $620 billion in uncompensated care to their patients” since 2000.

This figure is not directly related to the addiction crisis, but addiction specialists say many people experiencing substance use disorders don’t have health insurance.

Gee explained to West Virginia Public Broadcasting how these costs can add up, using Ruby Memorial Hospital in Morgantown, West Virginia, as an example.

“We have about 25 to 30 opioid patients in our hospital right now who are in need of heart valve replacements. And this is part of the result of the opioid crisis. Each one of those people will stay in our hospital for 50 to 60 days, a lot of it unreimbursed. So this is in the order of millions of dollars of uncompensated care,” he said.

“They were required to pay $246 billion. And what we found is that an awful lot of that money never really went to tobacco cessation,” he said.

Spending Control

Part of the conversation surrounding the court case is deciding who should control how money from a judgment or settlement is spent.

Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost attempted to get ahead of county and local litigation, requesting in August that their cases be put on hold until the states made their arguments.

He claimed that the states have sole right to pursue these claims on behalf of their citizens.

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in Cincinnati rejected this argument, and criticized the timing of Yost’s action because there had already been settlements and the local cases were very close to trial.

Yost also raised the ire of local officials with reported draft legislation (which has not been introduced) that would give his office and outside attorneys trying the case each a five percent share of any settlement or judgment, then allow the state legislature to allocate the remaining money.

Yost recently clarified his position, saying that any money from the litigation should be spent on the local level.

“Many of the impacts have been statewide, so (state control) makes sense, but I think there should be room for local communities to have a say,” he said. “The impacts of opiates have been widespread, and so there are a number of systems that have been impacted and should be reimbursed – child welfare, law enforcement and so forth.”

Above everything, Gay hopes whoever controls the money uses it to supplement existing funding.

“I would like to see at least some of the money go to treatment and that it not simply replace funding that now exists, but that it increases the amount of money available.”

Complex Case

A judicial panel ruled that the roughly 2,000 cases against opioid companies would be consolidated into the National Prescription Opiate Litigation and assigned to Federal Judge Dan Polster in Cleveland.

The first such case brought by Cuyahoga and Summit Counties in Ohio was against several companies the plaintiffs claimed created a public nuisance by fueling the opioid epidemic.

In a separate case, a court in Oklahoma found Johnson & Johnson liable under the state’s public nuisance laws for more than half a billion dollars.

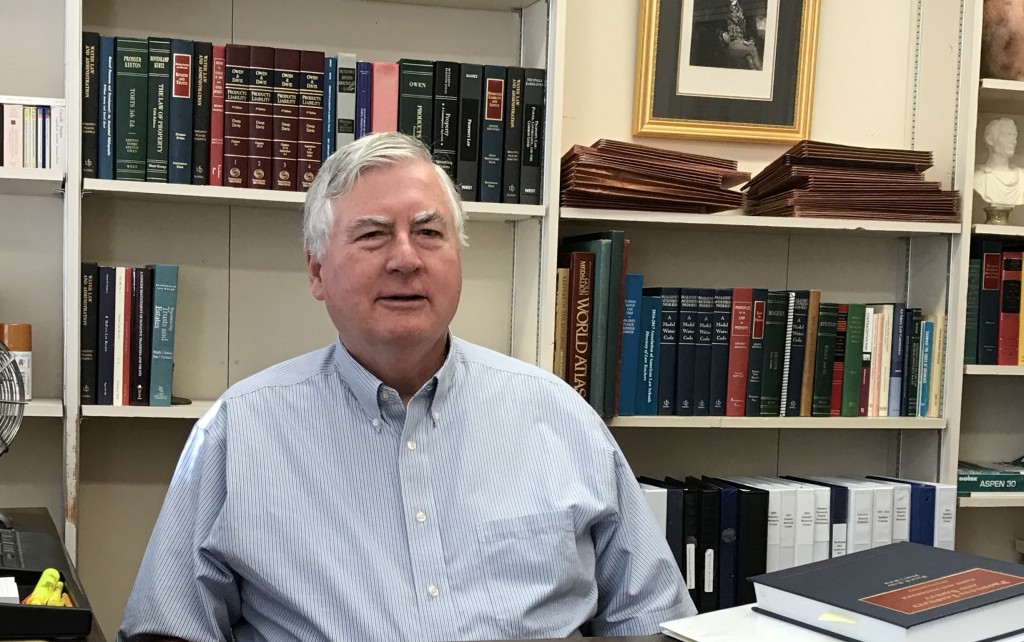

University of Kentucky Law Professor Richard Ausness specializes in studying product liability litigation. He said Ohio’s public nuisance law is different and viewed differently in court, but Johnson & Johnson still settled with the two Ohio Counties for $20 million.

Oxycontin maker Purdue Pharma was initially named as a defendant in the case, but all cases were delayed for six months by Judge Polser after the company filed for bankruptcy.

Ausness believes the state attorneys general and lawyers representing the county and local governments, as well as the opioid manufacturers, distributors and pharmacies likely want to reach a master settlement. But it could be challenging deciding who pays what.

The settlement announced Monday buys more time to discuss a master settlement before the next scheduled federal trial.

Whether money comes from a settlement or the outcome of a trial, researchers believe the money awarded from these cases won’t be enough to offset the damage done by the opioid epidemic.

But for rural areas across the Ohio Valley where the crisis hit hardest, they’ll take anything they could get.

West Virginia Public Broadcasting and Ohio Public Radio contributed to this story.

This story has been updated to reflect the settlement announced Monday, Oct. 21.