News

Portal 31: How A Closed Mine Opened New Prospects For One Coal Town

By: Brittany Patterson | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Devin Mefford is sitting in the squat metal buggy of a modified mantrip, the train-like shuttle coal miners use to travel underground. Mefford is dressed for work, in a hardhat and a navy shirt and pants with lime green reflective stripes.

It’s a uniform his father and grandfather — both Kentucky coal miners — would be familiar with.

Mefford does go into a mine every day, but not for the coal. He’s the tour guide at Portal 31, a train ride through a once-operational coal mine in Harlan County.

“People are amazed,” the 21-year-old says, gesturing to the dark mine entrance behind him.

When it closed its doors in 1963, Portal 31 had produced more than 120 million tons of coal. More than 40 years later, in 2009, the mine reopened — this time to tourists.

For 35 minutes visitors ride the rail cars, often in pitch darkness, on a journey not just through the mine, but back in time. The drawling voice of an actor playing a miner named Mike Mackenzie, or Mac, narrates.

“We’re going to visit the miners and see how it’s changed over the years,” he says. “First stop, 1919.”

An animatronic miner materializes out of the darkness. Another actor gives voice to an Italian immigrant named Joseph, who recounts what it was like for the thousands of people who came to work in the mines in the early 1900s. Next to his lifelike form is a robotic mule and chirping canary.

“The mine she’s cool and safe,” he says. “You will see to that won’t you cantante. As long as I can hear your song I know I’m safe.”

“This is a story that never needs to die. It’s a story that needs to be told,” Nick Sturgill, director of Portal 31 said. “People need to understand what these guys went through, but they also need to understand how prosperous a place this was at one time — what coal not only did for this city, but for this region, for this country, for this entire world.”

He said about 5,000 visitors from around the world take the ride under Black Mountain each year. It’s a bright spot for Lynch, which today is home to just a few hundred residents.

Like many former mining communities, in recent years Lynch and neighboring towns have turned their sights on attracting tourists. It’s often a costly endeavor, but in recent years the federal government has expanded its support for repurposing old mine lands as new economic engines, including to draw new visitors.

Federal Role

as nearby historic buildings for use as retail and office space. Some of the money is slated to go to a new parking lot and scenic overlook at nearby Black Mountain.

“The main outlook on the AML grant is to really just be a shot in the arm for all of Lynch as well as Harlan County,” Sturgill said.

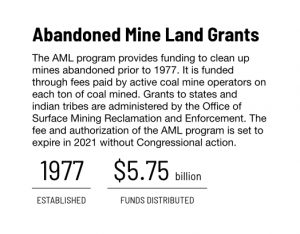

Central Appalachia has thousands of acres of abandoned mine sites that can threaten local economies and people’s health and safety. In 1977, Congress created the Abandoned Mine Land Reclamation Program to clean them up. The funds come from fees paid by active coal mine operators on each ton of coal mined. The fee and authorization of the AML Program is set to expire in 2021 without Congressional action.

The Appalachian Regional Commission in 2015 began investing in coal-impacted communities through Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization, or POWER Initiative. Congress appropriated money from the U.S. Treasury to create the AML Pilot program in 2016, aimed at not only boosting reclamation work in the highest-need Appalachian states, but promoting projects that spur economic development and growth on abandoned mine lands.

“There’s significant economic benefits that communities can get from embracing mine reclamation,” said Joey James, with the Reclaiming Appalachia Coalition, which advocates for sustainable reclamation investment. “There’s also opportunities to repower some of these sites that were once the lifeblood of these communities.”

“While these federal programs are really, really important, and we need to have them, I think what the AML Pilot program does is it offers an opportunity to develop enterprises on former mine sites that might pull private capital and create models for redeveloping and reusing mine sites that won’t rely entirely on federal funding,” he said.

Another federal proposal, the RECLAIM Act, would accelerate reclamation of abandoned mine land by dispersing $1 billion of Abandoned Mine Land funds over a 5-year period with an eye toward economic development. That bill has not been passed by Congress despite bipartisan support.

Critics argue the millions poured into these programs have failed to produce the desired outcomes. Some efforts planting lavender or apple trees on old strip mines have floundered. James said it’s important to objectively assess the effectiveness of projects receiving federal funding.

“If states are investing in projects that aren’t providing that opportunity in the future, we need to think of how we can be better,” he said.

Growing Pride

Back inside Portal 31, the mantrip snakes its way back toward daylight.

A group of visitors from South Carolina is milling around in the small gift shop. They’re visiting the area on a mission trip. A gaggle of middle school-aged kids excitedly share what they learned.

“We learned how difficult it was and how dangerous it is for them,” one says. Another adds his amazement that Portal 31 holds the record for most coal mined in a single day — a record set in 1923.

“In all honesty, coal mining is a thing of the past, and it’s sad to say that for small towns like mine,” he says.

But he adds that makes Portal 31, and federal investment into both preserving and showcasing Kentucky’s coal heritage, even more important.

“Every person in this community deserves to have something to be proud of, and that’s what we do here,” he said.