News

“The Proof Is In The Pudding.” Coal Country Responds To Democrats’ Clean Energy Transition

By: Brittany Patterson | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NPR) — Democrats made their pitch to the American people during a largely virtual Democratic National Convention and addressing climate change emerged as a central tenet of the party’s plan.

The party platform spells out a major investment in green energy jobs and infrastructure in order for America to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emission no later than by 2050. Environmental justice is a key component of the Democrat’s climate plan and it references ensuring fossil fuel workers and communities receive investment and support during this clean energy transition.

The $2 trillion proposal has big implications for areas of the country whose economies are built on fossil fuel extraction, including the coal-heavy Ohio Valley. For over a decade, communities in the region have reckoned with the energy transition as coal demand shrinks. Since 2009, coal production and employment have fallen by roughly 50 percent in the Ohio Valley as power generators sought out less expensive and cleaner energy sources including natural gas and renewable energy. That decline has sharpened due to the recent coronavirus economic fallout.

In recent months, multiple regional coalitions have put forward policy blueprints aimed at putting Appalachia and its needs front and center in this growing national conversation around a “just transition.”

As the 2020 election season heats up, they’re urging political leaders to continue the dialogue with residents of Appalachia in order to deliver on party platform promises as the energy transition accelerates.

Grassroots Response

“In the national arena Appalachia is and will continue to be a political stumbling block to national climate change legislation until we figure out what Appalachia really needs,” said Amanda Woodrum, co-director of ReImagine Appalachia, a coalition of progressive policy and environmental groups that recently released a framework for the region as it shifts away from resource extraction.

She said many of the ideas in the Democratic Party platform are exciting. The document pledges 40 percent of investment in vulnerable communities. It also explicitly recognizes that coal miners and power plant workers will be impacted as the economy shifts toward more clean energy, and advocates for the protection of retirees’ health and pension benefits.

“I think one of my concerns, though, is that it only actually mentions Appalachia once, and we believe that there needs to be a completely concentrated and focused effort on what the needs are of Appalachia,” Woodrum said.

And those needs look different than in other extraction-based economies, said Joanne Kilgour, executive director of the Ohio River Valley Institute, a new think tank focused on the region. Unlike some fossil fuel-based economies such as Alaska and Wyoming, states such as West Virginia and Kentucky have not created funds aimed at marshaling financial resources from resource extraction that could be used to invest in a transition.

Appalachia never fully recovered from the Great Recession and, like much of the country, is now reeling from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kilgour urged policymakers to lean on the grassroots groups doing transition work in the region. That includes the National Economic Transition Platform.

Brandon Dennison is the founder and CEO of Coalfield Development, a not-for-profit organization in southern West Virginia dedicated to rebuilding the region’s economy in sustainable ways. He said in Appalachia one thing that needs to be recognized is the sacrifice made by those who mined coal for decades.

“It’s not about a handout,” he said. “It’s really about our country honoring the incredible sacrifices folks and fossil fuel areas have made to power this country’s development and to get this country where it is today.”

Politicians have left promises unfulfilled in Appalachia, he said, and while he sees promise in the Democratic party platform, he said he understands if it doesn’t resonate with voters here.

“You know, the proof will have to be in the pudding, so to speak,” he said.

Labor Reaction

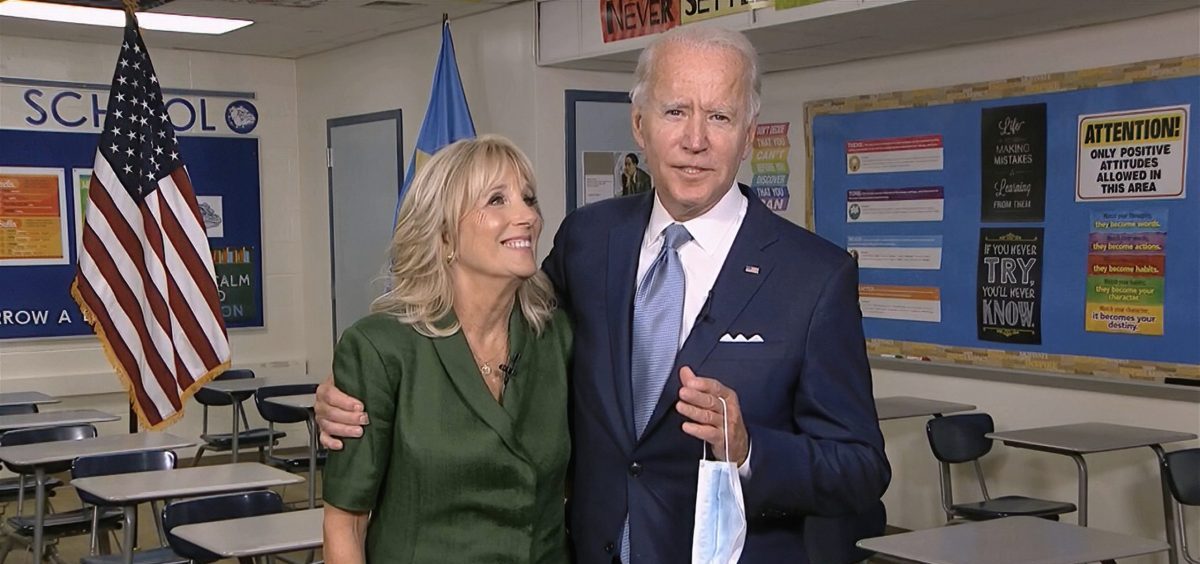

More details would also please the United Mine Workers of America, which has been involved in conversations with the Biden campaign.

.@DNC talking about energy jobs while showing solar panel installers is troubling. None are union, all are contractors to avoid organizing. Dem climate plan still needs concrete, specific solution for traditional energy workers besides “trust us.” #DemConvention2020

— United Mine Workers (@MineWorkers) August 20, 2020

Spokesperson Phil Smith said the union fully acknowledges the country is moving away from coal toward cleaner energy, but the bulk of solar jobs, for example, are not “good union jobs” as the Biden ticket promises.

“There are some in the Democratic Party hierarchy, who buy into the notion that we can just set up a commission and everything will be fine, and we can spend money and train people to do something else and everything will be fine,” he said. “That’s not going to work. That is not a transition; that is pushing a problem away.”

This story is the first in a series revisiting themes, places and people in the new Ohio Valley ReSource book, “Appalachian Fall.”