News

Ohio University Enrollment On Path To Continue Slide As Peers Project Gains

By: David Forster

Posted on:

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB) — Ohio University is on track for one of its lowest undergraduate enrollments in several decades, which will have financial repercussions for years to come.

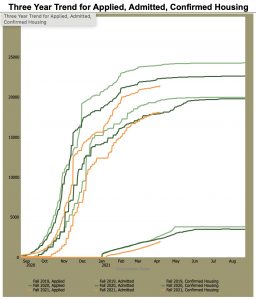

The deadline for incoming freshmen to submit their housing deposits is less than four weeks away. So far, the number of confirmed freshmen enrollments at Ohio University for the coming school year is lagging well behind last year’s numbers. Some of this is related to the coronavirus pandemic.

Meanwhile, some of the universities that Ohio University competes with most directly for students are projecting enrollment gains, although it’s too soon to tell whether they will meet those projections.

Enrollment at Ohio University has been declining for years and is expected to continue dropping for a couple more years. University leaders say one of the reasons enrollment is declining at Ohio University while holding steady or even increasing at other Ohio universities has a lot to do with marketing and branding.

Senior administrators say competition for students has become much more aggressive and sophisticated and that some of the other universities were faster to develop new efforts to target and recruit students.

Ohio University has been playing catch-up. Changes senior administrators have made recently are designed to make the university more competitive, but it will take some time to reverse the years of declines.

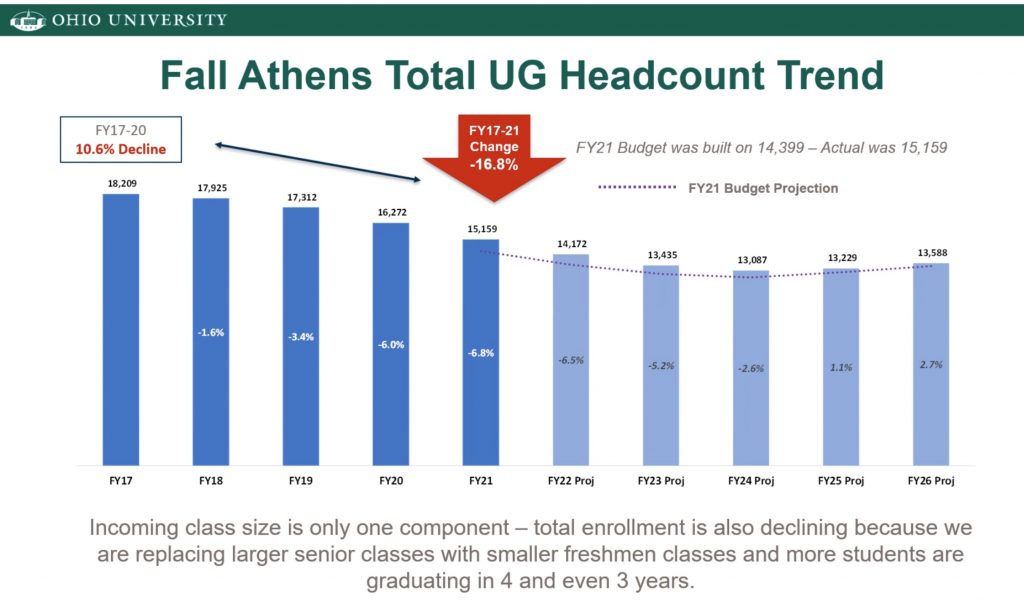

A recent presentation on the university’s financial situation included enrollment projections for the next several years. The projection for the 2021-22 school year was 14,172 total undergraduate students for the Athens campus. Enrollment was projected to bottom out two years later at 13,087 students. That would be a decline of more than 5,000 students, or 28 percent, since enrollment peaked in the 2016-17 school year at 18,209.

These projections may change when university leaders present enrollment updates to the board of trustees at its meeting Thursday and Friday.

The deadline for incoming freshmen to submit their housing deposits is May 1, which is viewed as a critical date when it comes to gauging the size of the new freshmen class. The vast majority of incoming freshmen typically enroll by that date, although enrollments continue to trickle in afterward.

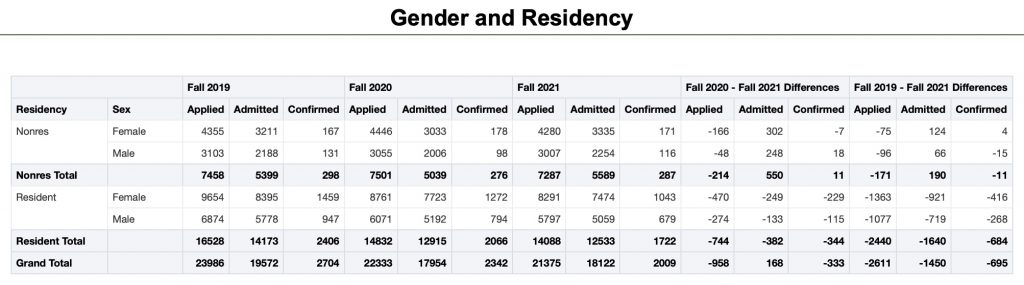

An admissions report run late Wednesday afternoon shows that 2,009 freshmen have confirmed their enrollment so far at Ohio University. This is 333, or 14.2 percent, fewer than last year at this time, several months into the global coronavirus pandemic, and 695, or 25.7 percent, fewer than this time two years ago.

Ohio University also saw a decline in the number of freshmen applications for the coming school year. It received 21,375 applications so far this year, down 958, or 4.3 percent, from this time last year, and down 2,611, or 10.9 percent, from the year before.

University officials say it’s too soon to read too much into the enrollment numbers. Enrollment confirmations are lagging behind the usual pace, likely because the pandemic is leading many prospective students to delay making their enrollment decisions this year.

But even if there is a last-minute surge in confirmations in the coming weeks, the incoming freshmen class likely will be the smallest, or at least one of the smallest, since the mid-1980s or early 1990s. The same is true of the total undergraduate enrollment the university is projecting for the coming school year. The last time undergraduate enrollment was below 15,000 was in 1990.

Other Ohio universities are also seeing enrollment confirmations coming in at a slower place. However, three of the universities Ohio University competes with most directly for students are still projecting strong enrollment.

Ohio State University, University of Cincinnati and Miami University saw significant increases in applications for the coming year compared with previous years. Cincinnati and Miami both project their incoming freshmen class will be larger than this school year. Ohio State said it is deliberately reducing the size of its incoming freshmen class to a more typical level after enrolling an unusually large class this school year because of the uncertainties created by the pandemic.

Total undergraduate enrollment has for the most part been trending upward on the main campuses at all three universities. Cincinnati has seen eight straight years of record enrollment, including this school year in the midst of the pandemic. A university spokesman said Cincinnati is expecting to set another record in the coming school year.

Ohio State has also seen year after year of record undergraduate enrollment over the past several years, with the exception of one year when enrollment was flat. This school year’s enrollment set another record.

Undergraduate enrollment at Miami had been climbing steadily for the past decade but dipped slightly in the 2019-20 school year and then saw a more significant drop this school year as universities around the state and the nation saw enrollment declines linked to the pandemic. Miami officials presented the university’s board of trustees with two projections for undergraduate enrollment in the coming year, one showing a slight dip from last year and the other showing a slight gain.

To a certain degree, the enrollment gains at these universities are Ohio University’s loss. Most of the students who enroll at Ohio public universities are Ohio residents. At Ohio University, a little over 80 percent of undergraduates are Ohio residents; at Ohio State and Cincinnati it’s about 75 percent; and at Miami it’s about 60 percent.

The number of high school graduates in Ohio, and the percentage of these graduates who enroll in an Ohio college or university, hasn’t changed much over the past several years. So, if other universities are taking a larger share of these graduates, that is going to affect Ohio University’s enrollment.

And this is in fact what has happened. The 2016-17 school year was the last of Ohio University’s decade-long run of record enrollment gains. That year the university captured 10.8 percent of the Ohio high school graduates who enrolled at a university. Since then, that percentage has dropped steadily to 7.9 percent this school year.

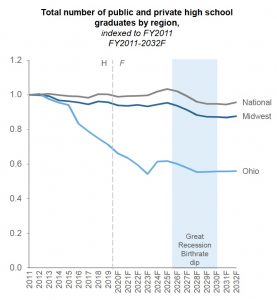

Ohio University officials attribute this decline in market share to increasing competition for students. Some of this stems from a 2016 report by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. Universities around the nation use the commission’s projections to help with enrollment planning.

The 2016 report projected a national decline in the number of high school graduates that would last for many years. This decline would be particularly acute in the Midwest and especially in Ohio.

The report set off alarm bells in university enrollment offices. Many responded by stepping up their marketing and recruiting efforts, including offering more generous financial aid packages to prospective students.

Ohio University was slower to respond. University officials at the time expected enrollment to plateau or even drop somewhat, but nothing significant. But as one enrollment projection after another turned out to be too optimistic, and the university’s budget surpluses turned into deficits, the board of trustees urged university officials to be ever more conservative in their forecasts.

As enrollment declined, university leaders pointed to declining numbers of Ohio high school graduates as one of the reasons. For example, at a retreat last August to discuss the university’s enrollment and budget issues, the board was presented with a chart showing a sharp decline in Ohio high school graduates beginning about a decade ago and continuing through 2020 before starting to level off.

But that decline did not in fact happen. The alarming projections by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education were wrong, at least so far in Ohio. And so, declining enrollment at Ohio University was not the result of a shrinking pool of Ohio high school graduates.

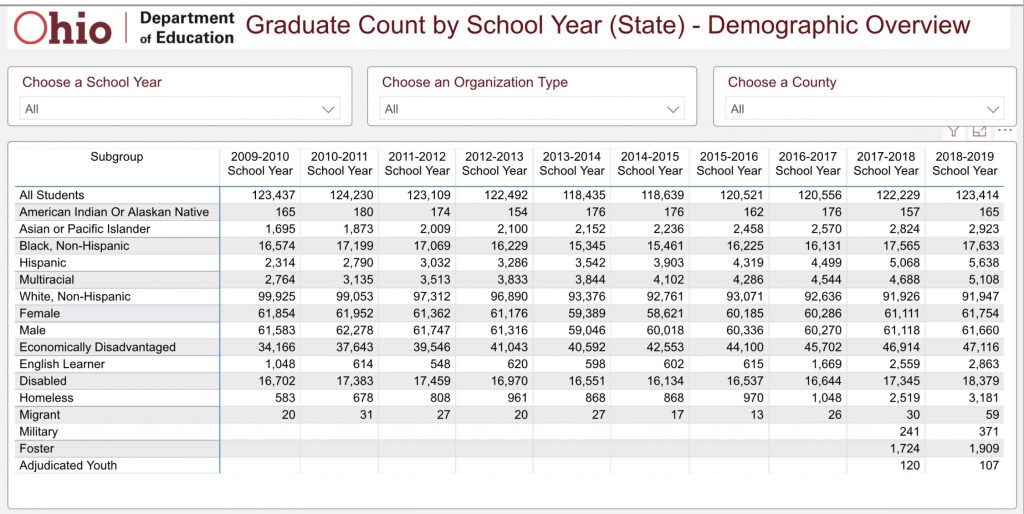

Data from the Ohio Department of Education, which gets its numbers directly from the state’s high schools, show that the number of high school graduates has held fairly steady over the past decade. The data show 123,414 graduates in the 2018-19 school year, the most recent year for which data is available because of the time it takes to collect and compile the information. This was just a few students shy of the 123,437 graduates in the 2009-10 school year. In the years in between, the number of graduates did dip in the 2013-14 and the 2014-15 school years but then climbed back up.

The department collects data from every public school in the state and every private or parochial school that accepts government funding. A spokesperson for the department said that the number of students not captured by the data would not change the overall trend line.

But it’s not just the raw number of Ohio high school graduates that matters most. It’s the number of graduates who end up going to college. The Ohio Department of Higher Education compiles this data, and it shows that the number of Ohio public high school graduates enrolling at an Ohio college or university has also remained fairly steady over the past several years.

Ohio University leaders acknowledge that the commission’s dire demographic projections were wrong, at least so far, and no longer point to declining numbers of graduates as a factor in the university’s enrollment declines.

Candace Boeninger, the university’s vice president for strategic enrollment management, says her team still uses the commission’s projections for enrollment planning, but only to the extent that they track with reality.

“We look at WICHE data to understand future possible trends,” she said. “We’re not using it to reflect on what historically happened.”

The commission’s 2016 projections were wrong, but they still ended up having a profound effect on enrollment, Ohio University officials say. What happened is that other universities became much more competitive with their marketing and recruiting strategies when those alarming projections came out several years ago and that Ohio University simply fell behind.

“We saw some of our peer institutions getting out in front of us,” said Robin Oliver, vice president of communications and marketing. “Our marketing outfit was not built to be competitive in the modern landscape.”

Senior officials say the university has undergone a comprehensive overhaul and realignment of its marketing and recruiting operations. This included making the university’s chief of communications a key player in strategic enrollment planning.

One of the first steps in the realignment was to consolidate communications for the university’s colleges and schools into the central office. The goal is to ensure consistent messaging and branding in the university’s public outreach.

Focus group research has shown that Ohio University as a whole does not have an overarching brand identity that resonates with prospective students, which officials believe is essential to strategically position and promote the university in a highly competitive landscape. Recent marketing efforts include building a stronger digital presence to meet prospective students where they are, especially on social media.

But better marketing alone won’t solve the enrollment declines. “There is no silver bullet solution to this challenge because it is not one singular thing,” Oliver said. “We simply have to tackle all of them.”

Another challenge the university faces is that it’s tuition is second-highest in the state, behind Miami. This includes not just the published sticker price but also the net price, which is the average tuition students pay after discounts for financial aid awards.

“We are looking at price,” Boeninger said. “I think we are very mindful of that right now.”

Elizabeth Sayrs, the university’s executive vice president and provost, put it more bluntly in a recent presentation to one of the university’s colleges: “We can’t be second in the state.”

The university is offering more financial aid to prospective students as an incentive, as are other universities in Ohio and nationwide. But this financial aid is really just discounts off the tuition price, which means that the more aid offered, the lower the net tuition revenue at a time when declining enrollments at Ohio University have created budget deficits resulting in layoffs and other cost-cutting measures.

The financial consequences of smaller enrollments create a ripple effect for the university. Ohio University, like most public universities in the state, offers a tuition guarantee, meaning that the tuition incoming freshmen pay is fixed through their senior year. So with each successive smaller incoming class, that’s four years of lower revenue.

Declining enrollment also affects how much money the university gets from the state, which accounts for about 25 percent of its revenue. Each university’s share is based on the number of courses completed and degrees conferred. So, smaller classes result in smaller shares of state funding for years to come.