News

Japan Aims To Convince A Wary Public The Olympics Will Be Safe

By: Anthony Kuhn | NPR

Posted on:

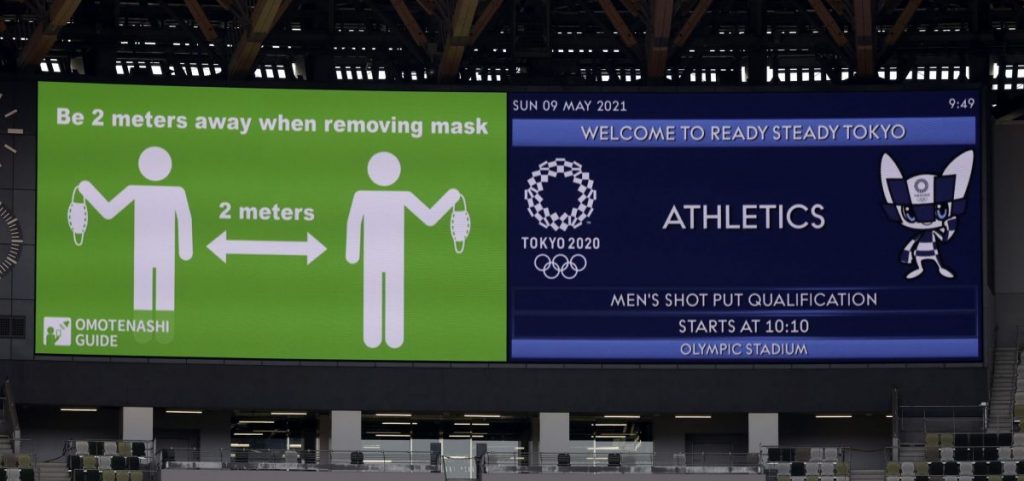

TOKYO, Japan (NPR) — Olympic organizers and Japan’s government are ramping up vaccinations, inside and outside the Olympic Village. It remains to be seen whether the push will be the antidote to widespread opposition in Japan to holding the games amid the pandemic and pervasive fear that the event will threaten public health.

The International Olympic Committee said Wednesday that about 75% of prospective Olympic and Paralympic athletes have either had their shots, or are scheduled to do so. It predicts more than 80% will be inoculated by the time the games start in just over six weeks.

Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said his goal is to finish vaccinating all citizens who want it by November. The government had previously targeted February 2022 as the date for completing vaccinations. Suga also pledged this week to further reduce the number of Olympic officials, staff and journalists coming into Japan.

Japan’s vaccine rollout is finally ramping up

While Japan’s vaccine rollout still lags behind other developed economies, the pace has picked up in recent days. At mass vaccination sites in Tokyo and Osaka, military medical staff has been inoculating older people. Japanese companies are setting up vaccination programs for employees after getting the green light this week from the government.

The faster jabs — and the arrival of the first athletes in Japan for pre-games training — may be helping to tamp down anti-Olympic sentiment. That was one possible interpretation of a Yomiuri Shimbun poll last weekend that saw the number of respondents calling for the games to be canceled drop by 11 points to 48%, compared with a similar poll last month. The poll found 50% in favor of going ahead with the games.

Anger at the government’s insistence on pushing ahead with the games has remained intense enough, though, to put Suga on the defensive this week.

“It is my responsibility to protect citizens’ lives and health,” he told lawmakers Monday. “If we cannot, then it’s only natural not to hold the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics.”

Suga has insisted that the government is taking sufficient measures to ensure the safety of athletes and Japan’s population. But the Yomiuri Shimbun poll found that most Japanese people are not confident that the measures will do the trick.

“I’m personally against the Olympics, of course because of the safety issue,” said resident Junji Momose, stopping to speak at Tokyo’s busy Shimbashi railway station. He worries that Japanese citizens are going out despite a state of emergency in effect across much of the country, “because they think: ‘It’s OK to go out because the Olympics is taking place.’ ”

Some experts are concerned the safety measures are insufficient

Some medical experts have focused on the Olympic playbook outlining measures to protect athletes and officials. The latest version, published in April, includes a colorful cover illustration, showing two judo athletes grappling, without masks on.

“The graphics are nicer than any of the information that’s in it,” comments Lisa Brosseau, a research consultant at the University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy.

In a recent article in The New England Journal of Medicine, she and her co-authors argue that “the IOC’s determination to proceed with the Olympic Games is not informed by the best scientific evidence.”

The playbooks, she argues, fail to include best practices for holding sporting events during a pandemic, such as housing no more than one athlete in each hotel room and using different approaches to manage different levels of risk, ranging from indoor boxing matches to outdoor sailing events.

Organizers should be considering: “Can you minimize contact? Can you minimize time? Can you minimize the number of people? Can you add ventilation?” she says. “You need to have that sort of thoughtful conversation about what are the risks and what are the controls. And that’s not what I’m seeing in the playbooks at all.”

Dr. Naoto Ueyama, who heads the Japan Doctors Union, says he is less concerned about the roughly 15,000 athletes than the tens of thousands of staff working behind the scenes.

“I’m most concerned about the volunteers,” he says. “I read that they are given only two masks and one bottle of hand sanitizer to deal with the situation. It’s too awful.”

Organizers say about 10,000 out of 80,000 Olympic volunteers have already quit, some due to the health risks, others because of sexist remarks of the former games organizing chief. The government says it’s considering vaccinating the remaining volunteers.

Ueyama also notes that each sporting venue is assigned a medical officer, to treat ailing athletes or spectators, although it’s not clear yet if any spectators will be allowed. But he says that some of these doctors have quit, too, because they’re needed to work at Japanese hospitals flooded with COVID-19 patients.

Japan’s “government doesn’t have authority to force medical resources to be used for the Olympics,” Ueyama argues, adding: “They haven’t secured enough human resources, logistical support and money. I don’t think such a plan will go well.”

Ueyama also finds it hard to believe that everyone at the games will be able to stick to social distancing rules. He says, “I’m afraid completely blocking communication among athletes will be difficult.”

The organizers, for example, plan to distribute 160,000 condoms to the athletes but no face masks, which the athletes will be expected to bring themselves. Organizers emphasize that handing out the prophylactics is meant to raise awareness of safe sex, and in light of the pandemic, athletes should take them home, rather than use them at the games.

Chie Kobayashi in Tokyo contributed to this report.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))