Communiqué

An exceptional baseball player and committed humanitarian, “Roberto Clemente” on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE – Oct. 23 at 11 pm

< < Back to an-exceptional-baseball-player-and-committed-humanitarian-roberto-clemente-on-american-experience-jan-25-at-9-pmAMERICAN EXPERIENCE

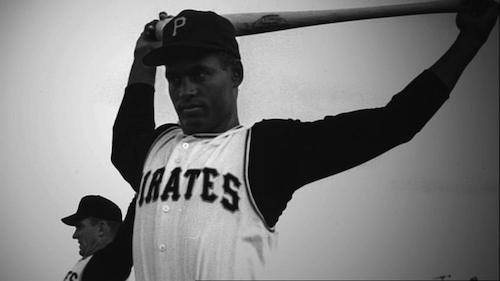

“Roberto Clemente”

Sunday, October 23, 2022

An Intimate Portrait of a Baseball Player and Humanitarian Whose Passion and Grace Made Him a Legend

On December 31, 1972, Roberto Clemente, a 37-year-old baseball player for the Pittsburgh Pirates, boarded a DC-7 aircraft loaded with relief supplies for survivors of a catastrophic earthquake in Managua, Nicaragua. Concerned over reports that the Nicaraguan dictatorship was misusing shipments of aid, Clemente, a native of neighboring Puerto Rico, hoped his involvement would persuade the government to distribute relief packages to the more than 300,000 people affected by the disaster. Shortly after takeoff, the overloaded aircraft plunged into the Atlantic Ocean, just one mile from the Puerto Rican coast. Roberto Clemente’s body was never recovered.

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE – “Roberto Clemente,” a documentary about an exceptional baseball player and committed humanitarian who challenged racial discrimination to become baseball’s first Latino superstar. From independent filmmaker Bernardo Ruiz, the program features interviews with Pulitzer Prize-winning authors David Maraniss (Clemente) and George F. Will (Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball), Clemente’s wife, Vera, Baseball Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda and former teammates to present an intimate and revealing portrait of a man whose passion and grace made him a legend.

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE – “Roberto Clemente,” a documentary about an exceptional baseball player and committed humanitarian who challenged racial discrimination to become baseball’s first Latino superstar. From independent filmmaker Bernardo Ruiz, the program features interviews with Pulitzer Prize-winning authors David Maraniss (Clemente) and George F. Will (Men at Work: The Craft of Baseball), Clemente’s wife, Vera, Baseball Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda and former teammates to present an intimate and revealing portrait of a man whose passion and grace made him a legend.

Clemente’s untimely death brought an end to a spectacular career. In his 18 seasons with the Pirates, he led the team to two World Series championships, won four National League batting titles, received the Most Valuable Player award and earned 12 consecutive Gold Gloves. In his final turn at bat for the 1972 season, Clemente made his 3,000th career hit.

Born in a poor rural barrio in Puerto Rico in 1934, Clemente grew up “with people who really had to struggle,” he later recalled. An avid baseball player throughout his youth, Clemente was drafted by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1954, just seven years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in major league baseball. As a black Latino, Clemente encountered many of the same obstacles and prejudices as the first African-American ball players. His starting bonus of $10,000 was just a fraction of the amount paid to white draftees, and during his first spring training in Florida in 1955, segregation laws meant that while Clemente’s white teammates relaxed at beaches, swam in pools and stayed in hotels that didn’t admit blacks, he was frequently forced to find his own lodging and eat meals on the bus.

Born in a poor rural barrio in Puerto Rico in 1934, Clemente grew up “with people who really had to struggle,” he later recalled. An avid baseball player throughout his youth, Clemente was drafted by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1954, just seven years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in major league baseball. As a black Latino, Clemente encountered many of the same obstacles and prejudices as the first African-American ball players. His starting bonus of $10,000 was just a fraction of the amount paid to white draftees, and during his first spring training in Florida in 1955, segregation laws meant that while Clemente’s white teammates relaxed at beaches, swam in pools and stayed in hotels that didn’t admit blacks, he was frequently forced to find his own lodging and eat meals on the bus.

Clemente was offended by the racism he encountered in the United States, an injustice he had not experienced growing up in Puerto Rico’s relaxed racial climate. Later in his career, after signing with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Clemente often felt estranged in the blue-collar steel town, where the white majority saw him as a black man and the African Americans labeled him a foreigner. The local sports press often took jabs at the rising star by quoting him in broken English.

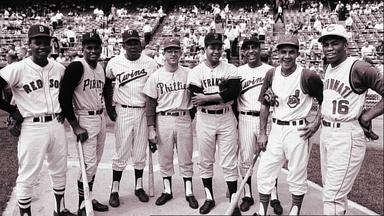

But by 1964, Clemente led a National League all-star team that featured more Latino players than ever. His success in baseball became an important symbol for the nation’s growing Latino population as he excelled in America’s pastime while maintaining his Latino identity. Today, 70 percent of foreign-born baseball players in the United States hail from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela or Puerto Rico.

But by 1964, Clemente led a National League all-star team that featured more Latino players than ever. His success in baseball became an important symbol for the nation’s growing Latino population as he excelled in America’s pastime while maintaining his Latino identity. Today, 70 percent of foreign-born baseball players in the United States hail from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela or Puerto Rico.

Eventually, Clemente used the podium his fame offered to talk about human rights and his dream to help underprivileged youth in Puerto Rico. During road trips with the Pirates, he routinely stopped to visit sick children in area hospitals. “If you have a chance to accomplish something that will make things better for people coming behind you, and you don’t do that, you are wasting your time on this earth,” he told a Houston audience in 1971, just one year before his death.