News

Where the gubernatorial candidates stand on Appalachian Ohio poverty

By: Theo Peck-Suzuki | Report for America

Posted on:

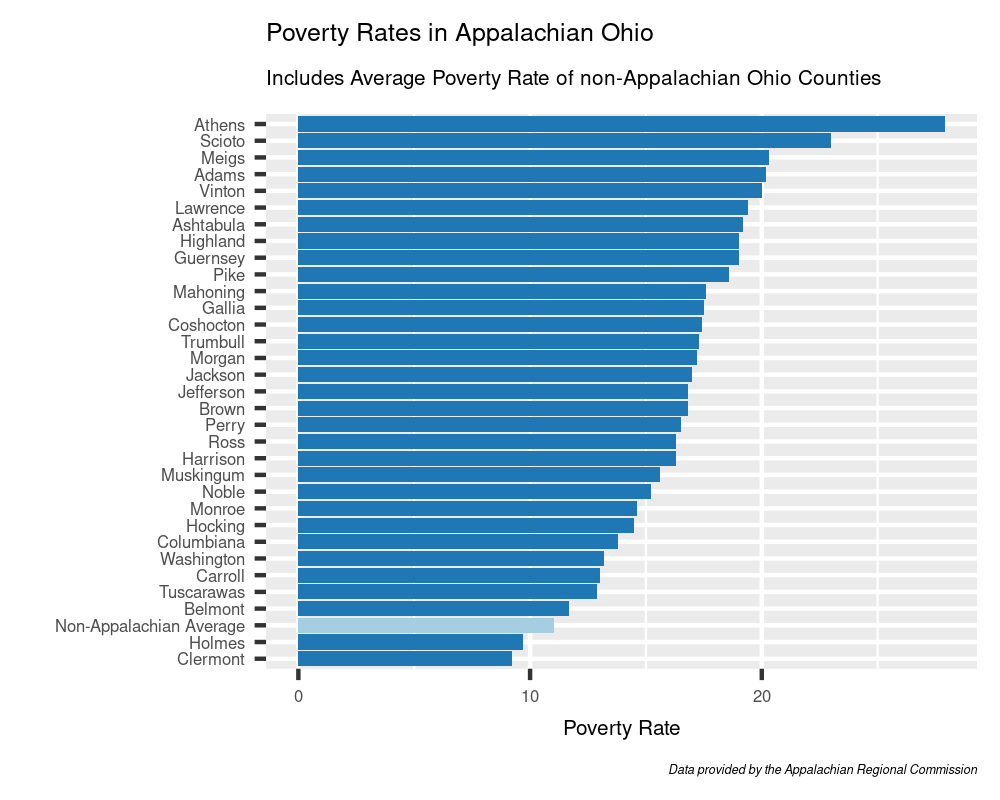

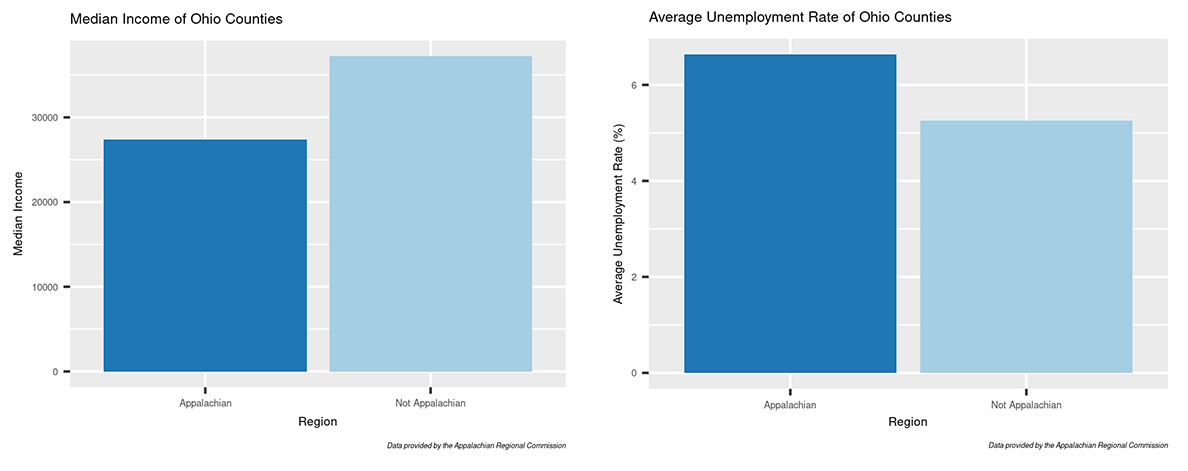

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB/Report for America) — Appalachian Ohio has long struggled economically in comparison to the rest of the state. Today, data from the Appalachian Regional Commission and Feeding America’s Map the Meal Gap program show that the region continues to suffer from disproportionately high levels of poverty and food insecurity.

The ARC regularly collects and analyzes data on counties across the United States, then uses that information to assess the development of Appalachian counties specifically. The latest data from ARC show that Ohio’s Appalachian counties perform worse than non-Appalachian Ohio counties in a number of ways:

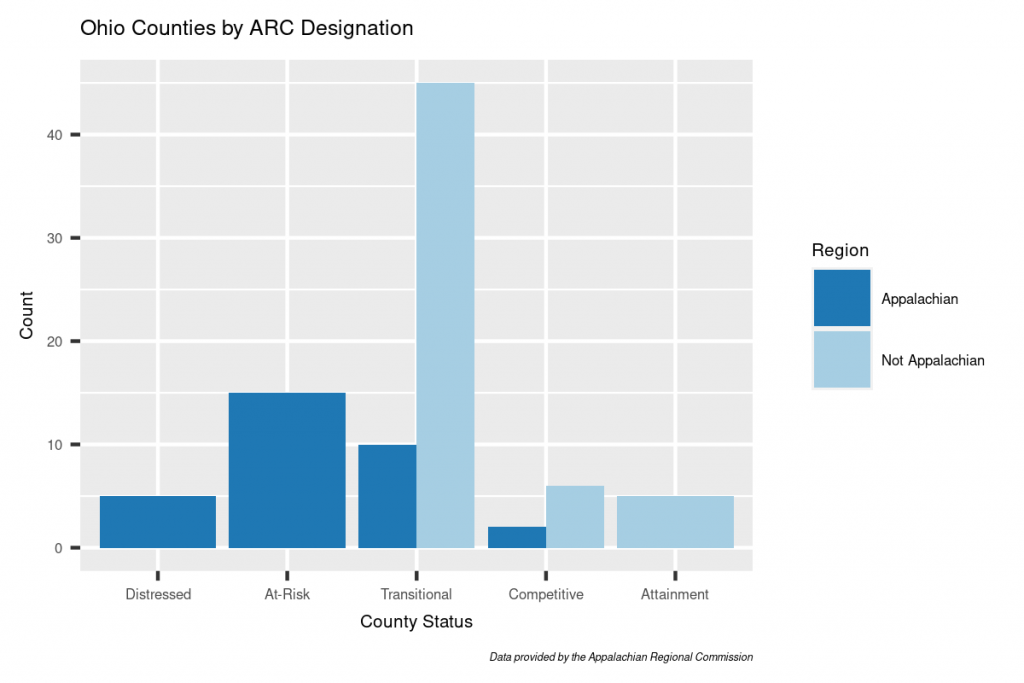

The ARC uses information like this to create five designations for counties based on their economic strength: distressed, at-risk, transitional, competitive and attainment. Distressed and at-risk counties rank among the worst 25% of counties in the United States.

Appalachian Ohio has 20 counties in the distressed or at-risk designation. There are no distressed or at-risk counties elsewhere in the state.

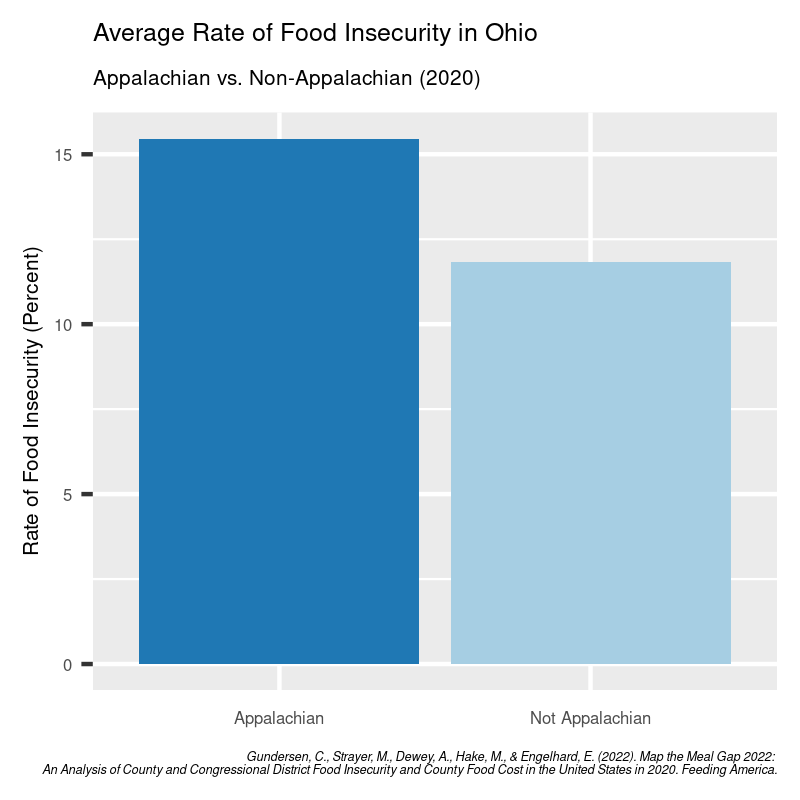

While these measurements are useful for understanding broad economic trends, they don’t offer a clear picture of what this all means for the people living in these counties. To get a better sense of this, it can be helpful to consider data on food insecurity.

Feeding America’s Map the Meal Gap program considers any household “food insecure” when its occupants are unable to get the food they need at least some days of the week. Many food insecure households are not always out of food, but rather run low on food on certain days.

People respond to food shortages in a variety of different ways. These include parents reducing their own portions to feed their children, drinking more water to fill the space left by missed calories, or skipping entire meals.

Feeding America’s most recent data is from 2020, a couple of years behind the ARC’s. Nevertheless, it paints a similar picture.

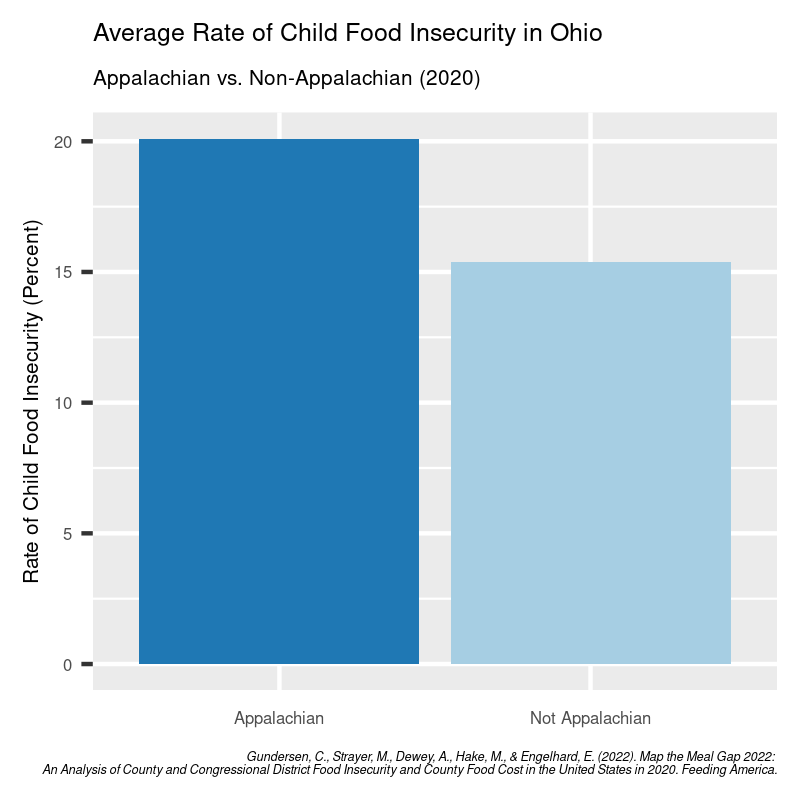

The disparity is even greater with regard to child food insecurity. One in five Appalachian children were food insecure in 2020.

As part of its work, Feeding America estimates the food budget shortfall for families in each county. The total estimated shortfall for all families in Appalachian Ohio in 2020 was $147,860,000.

This number comes from Feeding America’s estimation of how much an average meal costs in each county and how many food insecure people live there.

It is not currently clear what food insecurity looks like this year, though a dramatic change would be highly unusual. And although numbers for 2022 are not yet available, there are signs that the food crisis is worsening amid inflation and supply chain issues.

Where the Candidates Stand

Both incumbent Republican Gov. Mike DeWine and his challenger, Democrat and Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley, have articulated plans to address poverty in Ohio and specifically in its Appalachian Counties. Most of these plans focus on incentivizing job growth by bringing new businesses into the region and improving local infrastructure.

Whaley has stated that she wants to provide universal broadband access across Appalachia by 2028. She plans to do this by convening an Appalachia Universal Broadband Action Team, which will leverage a range of stakeholders to build a strategy for achieving her vision.

In terms of job growth, DeWine has touted his role in bringing the $20 billion Intel factory to Ohio, which will create an estimated 7,000 construction jobs during the build, 3,000 jobs at the factory itself, and tens of thousands of auxiliary jobs.

The Intel factory is being constructed in Licking County, which is not considered Appalachian, but it borders three Appalachian counties: Holmes, Perry and Coshocton. Of those, the ARC identifies Holmes County as competitive (top 25% of counties nationwide), Perry as transitional (mid-50%), and Coshocton as at-risk (bottom 25%).

DeWine has also emphasized his tax cuts, which he argues have made the state more attractive to businesses, and his work promoting career training for non-college-educated adults.

Perhaps the most significant effort the DeWine administration has made to address poverty in Appalachian Ohio has been the $500 million Appalachian Community Grant Program, which cleared the General Assembly this summer. The administration recently released guidelines for the program, which aims to fund inter-county projects targeting workforce, infrastructure and healthcare development.

Facebook]

Whaley has made a number of her own suggestions for bringing job growth to the region. Much of her strategy revolves around positioning Appalachian Ohio at the forefront of new industries and technologies, which she would aim to accomplish through a combination of innovation funding, partnerships with local governments, and state investment.

Central to Whaley’s proposal is a focus on clean energy jobs, which Whaley says the state would invest in heavily under her leadership. That would include an emphasis on providing opportunities to workers previously in the fossil fuel industry.

Whaley also wants to strengthen connections between community colleges and other institutions offering vocational training in technology fields. And she wants to promote innovative farming practices she argues will boost Appalachian Ohio’s agriculture industry.

Whaley has also expressed support for unions, which she ties to wage growth. She has also stated that she wants to raise wages throughout the state.

Neither candidate has made significant statements about food insecurity in the state. However, the DeWine administration did recently release $15 million for food banks statewide to help reduce the shortages they were experiencing. That number was significant, but also far lower than what food banks themselves said they needed.

For her part, Whaley has proposed a $350 rebate to Ohioans making up to $80,000 a year to help mitigate the pain of inflation, which has affected food prices. She estimates this rebate to include approximately 7.4 million residents.

Theo Peck-Suzuki is a corps member with Report for America, a national service program that places journalists into local newsrooms. He covers Children and Poverty for WOUB Public Media.