News

The American Dream Is Harder To Find In Some Neighborhoods

By: John Ydstie | NPR

Posted on:

Does the neighborhood you grow up in determine how far you move up the economic ladder?

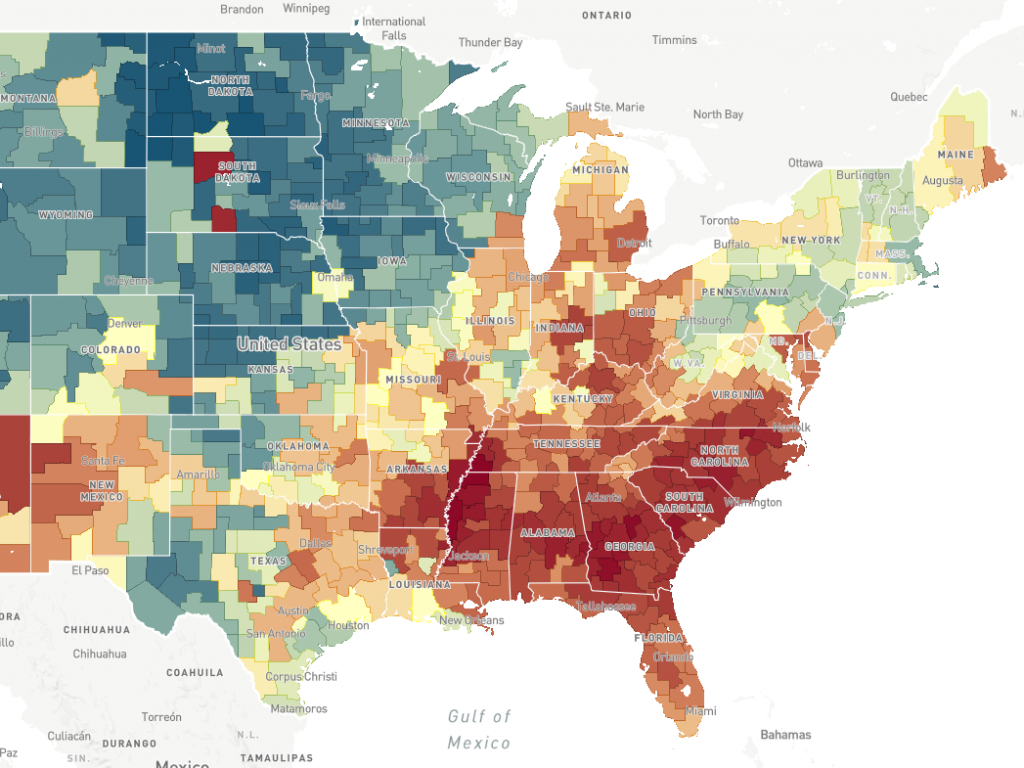

A new online data tool being made public Monday finds a strong correlation between where people are raised and their chances of achieving the American dream.

It used to be that people born in the 1940s or ’50s were virtually guaranteed to achieve the American dream of earning more than your parents did, Chetty says. But that’s not the case anymore.

“You see that for kids turning 30 today, who were born in the mid-1980s, only 50 percent of them go on to earn more than their parents did,” Chetty says. “It’s a coin flip as to whether you are now going to achieve the American dream.”

Chetty and his colleagues worked with the Census Bureau’s Sonya Porter and Maggie Jones to create the The Opportunity Atlas, which is available to the public starting Monday.

At first glance, it looks a lot like a Google map, where users can see the whole country, or zoom in to local neighborhoods. The difference is in the amount of data that pops up when a neighborhood is highlighted.

Researchers hope this data will help communities understand and tackle the barriers that prevent people from climbing the economic ladder. They want policymakers to use this data to offer new solutions locally.

Chetty explains that the government data they are working with is kept anonymous. The information can help pinpoint the places where lots of kids are climbing the income ladder and “the places where the outcomes don’t look as good,” he says.

Chetty found that if a person moves out of a neighborhood with worse prospects into to a neighborhood with better outlooks, that move increases lifetime earnings for low-income children by an average $200,000. Of course, moving a lot of people is impractical, so researchers are instead trying to help low-performing areas improve.

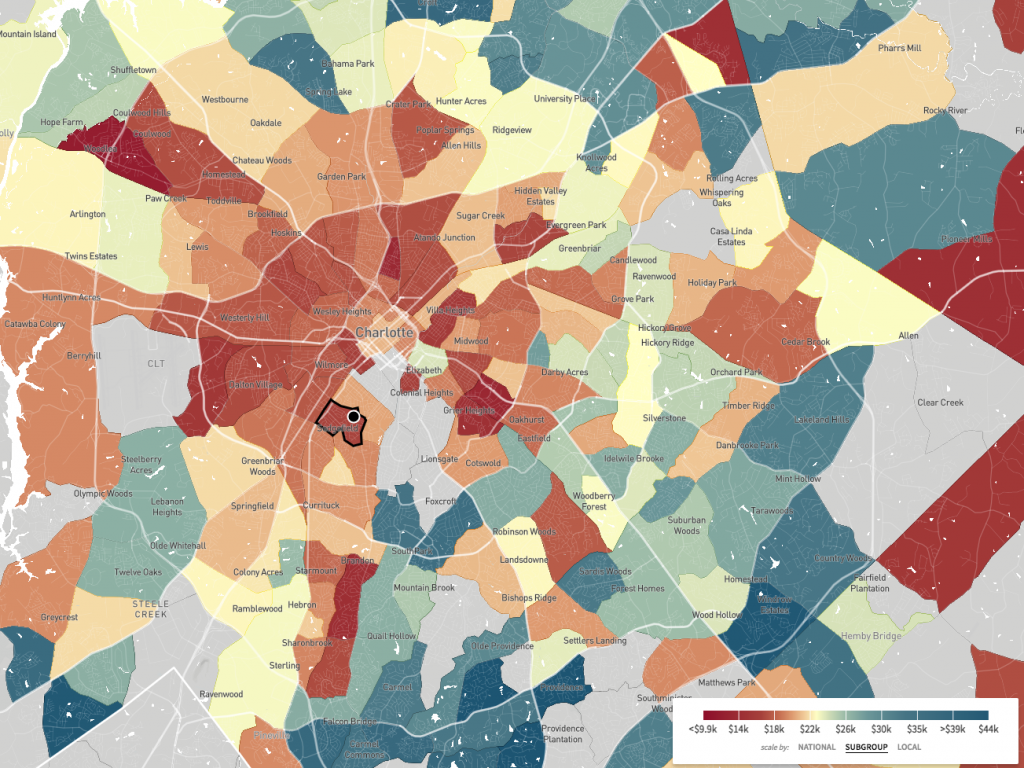

Charlotte, N.C., has gotten a head start on this effort. The city has enjoyed strong economic growth over the past couple of decades and many people assumed the progress had been shared across the city. But in 2014, Chetty and his colleagues released data showing that Charlotte was dead last out of 50 cities at providing upward mobility for low-income kids.

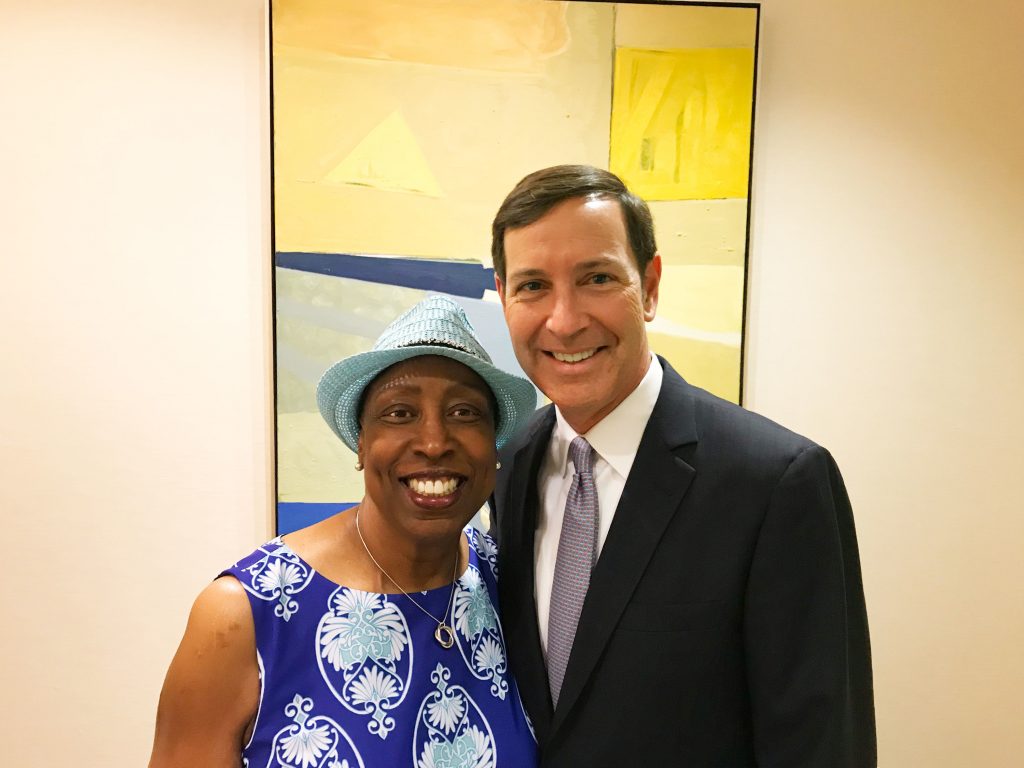

Dr. Ophelia Garmon-Brown, a prominent Charlotte resident, wasn’t surprised the city had done poorly.

“I’ve been a physician for a lot of years, worked with people who live in poverty, so I saw it,” she says. But Garmon-Brown says she was among those who were shocked that Charlotte had come in dead last.

And Charlotte responded, Garmon-Brown says. She was drafted to co-chair a task force, formed by the Foundation For The Carolinas, to develop a plan to attack the problem.

The task force’s report identified early childhood development, college and career readiness, family stability and strong social networks as key factors that enhance upward mobility. It singled out segregation as a key obstacle. And now, Charlotte officials are learning to use the Opportunity Atlas to effectively target some remedies, things like pre-K programs and affordable housing.

Frank Barnes, the chief equity officer for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, says the Opportunity Atlas will be very helpful in shaping future decisions.

The future is already taking shape at Sedgefield Middle School. It’s located in a majority white neighborhood not far from downtown Charlotte, but the school’s population doesn’t reflect the neighborhood. Assistant Principal Eric Tornfelt, says only 4 percent of the school’s student body is white; the rest is almost evenly split between African-American and Hispanic students.

Tornfelt acknowledges the school has challenges. “There is significant opportunity for growth,” as he puts it. “We have some great kids.”

James E. Ford, a former North Carolina teacher of the year, is working with Sedgefield’s administration to make the school more racially balanced. Ford, now an education consultant, says two local elementary schools have already merged for that reason.

“Eventually, something similar is going to happen here,” he says. “The demographics here are going to shift quite a bit. It’s majority black and brown now, but in the coming years it will change, it’ll start to look more like the neighborhood.”

But there’s another challenge here, beyond segregation — the lack of social networks minority children need to succeed.

The Sedgefield neighborhood is more affluent than a nearby majority black neighborhood called Southside Park. But the Opportunity Atlas shows that African-American men who grew up in Sedgefield in the 1980s and ’90s are doing worse now than their counterparts from Southside Park. The median income of African-American men in Sedgefield is $5,000 less per year than their neighbors in Southside Park.

Ford says that might surprise people.

“We may assume because the area is affluent, like, ‘that’s a high-opportunity area,’ when the truth is that may not be a high-opportunity area, according to all the metrics that we’re looking at,” he says.

Ford says the Opportunity Atlas should help reduce misconceptions about economic mobility.

“So this permits us to start making really smart and really intentional decisions so that, 20 to 30 years down the line we can look and say, ‘Yeah, that was the right call,’ ” he says.

Charlotte is already taking significant steps in that direction. Mecklenburg County, which encompasses the city, has committed to providing pre-K for all children. And the city has a $50 million bond issue for affordable housing on the November ballot. Matching private donations could boost the total to over $100 million.

Harvard’s Chetty says he hopes the Opportunity Atlas will help communities across the country revive the American dream in their neighborhoods.

“We hope citizens, local policymakers, nonprofits, people working on these decisions can use [the data tool] to make better decisions,” he says.

The Opportunity Atlas is now available to the public. You can find it at: http://www.opportunityatlas.org/

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))