Athens County’s Alternative Approach to Addiction

By: Michael Broerman, Natalie Colarossi, Omri Curnette, Rachael Beardsley

Posted on:

As the opioid epidemic continues to sweep Ohio, Athens county law enforcement is addressing the epidemic as a public health crisis rather than a criminal one, employing multiple programs to treat the overall problem of drug addiction.

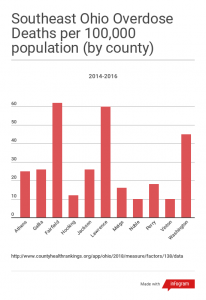

Ohio is rated in the top five for most opioid-related deaths in the country, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. In 2016, there were 3,613 opioid-related deaths in the state, more than double the national average.

In the past, those convicted of drug offenses were punished as criminals. However, this method gives little opportunity for recovery and often carries people back into the cycle of addiction. As a result, law enforcement in some areas are beginning to take a more holistic approach to the problem, finding ways to heal people rather than punish them.

Keller Blackburn, Athens County prosecutor, strives to look at the opioid epidemic from a compassionate perspective, employing new programs to aid those suffering from addiction.

“What law enforcement did before I took over this office, and what law enforcement does most places, is they try to punish people who have drugs, and they try to punish people who sell drugs,” he said. “[Here], we’ve tried to treat the underlying issue.”

His current initiatives include the county Vivitrol Program as well as a new outreach program to local schools.

The Vivitrol Program replaced the Suboxone Program, which Blackburn said was not effective because Suboxone still contains opioids. Vivitrol, on the other hand, blocks opioids from interacting with the brain entirely.

“Because you’re still getting that opiate, you still have that craving for that opiate, and when the Suboxone prescription would run out … they would still turn back to opiates,” Blackburn said. “Vivitrol is a cold-turkey kind of thing, it allows you to get treated and get counseling to deal with the things that caused you to use in the first place.”

“Because you’re still getting that opiate, you still have that craving for that opiate, and when the Suboxone prescription would run out … they would still turn back to opiates,” Blackburn said. “Vivitrol is a cold-turkey kind of thing, it allows you to get treated and get counseling to deal with the things that caused you to use in the first place.”

Early Education

On a separate front, the school outreach program will work to assess kids in the sixth, seventh and eighth grades and find those most likely to develop an addiction problem. The program will then teach decision-making skills that they hope will aid them in avoiding drug use. Blackburn said he hopes to have the program up and running soon.

“It’s less likely that they’ll choose to use drugs, and when they don’t choose to use drugs at a young age, the peer pressure that they would then put on the kids that are on the fringe [no longer exists],” he said.

Athens County has other initiatives to address the opioid epidemic. Project Deaths Avoided With Naloxone provides doses of naloxone, also known as Narcan, to community members at no cost once they complete a short training. Narcan blocks receptors in the brain to halt an opioid overdose, providing first responders enough time to administer further treatment.

“Anyone who needs Narcan or feels like they need to carry it because of a loved one or somebody they’re associated with, they can get Narcan through Project DAWN for free by completing the training,” said Sherleena Buchman, a professor in Ohio University’s College of Health Sciences and Professions and a practicing nurse.

At regular price, a two-dose Narcan kit costs around $130. Though certain types of insurance will pay some of the cost, the price is still too expensive for many people. Project DAWN increases public access to Narcan, Buchman said, and therefore increases the likelihood of more people surviving overdoses.

Though Narcan does prolong a person’s life and give them time to heal, Buchman said that Narcan does not fix the overall problem of addiction.

“I’ve heard people say it’s like a Band-Aid,” she said. “You’re fixing the situation for a minute, and that’s not the bigger problem, and I agree, but you have to have that Band-Aid because if you don’t, you’re losing lives.”

First-Hand Experience

Bryan Darst, a graduate of the Vivitrol Program, now serves as one avenue of help to those fighting the bigger problem of addiction. As one of two peer mentors in Athens County, he works with children’s services to help with case management and provide an understanding ear to those suffering from addiction.

“It’s a unique opportunity for not only the people who get to be the peer specialist, but also the people who get to receive services from them,” he said. “ For me, working with people who suffer from the same thing I suffer from, it kind of builds report when I walk through the door like listen, I’ve been to prison, I’ve been homeless, I’ve chose drugs over my children, and it’s a real unique opportunity because it helps ensure my sobriety at the same time.”

Darst added that law enforcement and healthcare professionals must focus on treating addiction as a whole.

“The reality of it is that we have a drug problem, period, and to classify it in one avenue, it’s ridiculous to try and do that,” Darst said. “If you want to address the issue, you have to address the whole issue.”

But Buchman said it can often be difficult for law enforcement and healthcare professionals to work together.

“I would say there’s not enough resources,” she said. “Law enforcement doesn’t have enough resources, healthcare doesn’t have enough resources, communities do not have enough resources, so there’s just not enough resources right now for that continuity.”

As Prosecutor, Blackburn is aiming to find that continuity by addressing the epidemic as a health problem, not a moral failing.

“The best way to stop new people from becoming users is programs, and academic development, and money into mental health,” he said. “The best way to stop users from using is treatment for their addiction.”