Culture

OU Prof’s Book Takes New Look at Hemingway

By: Jeff Worley

Posted on:

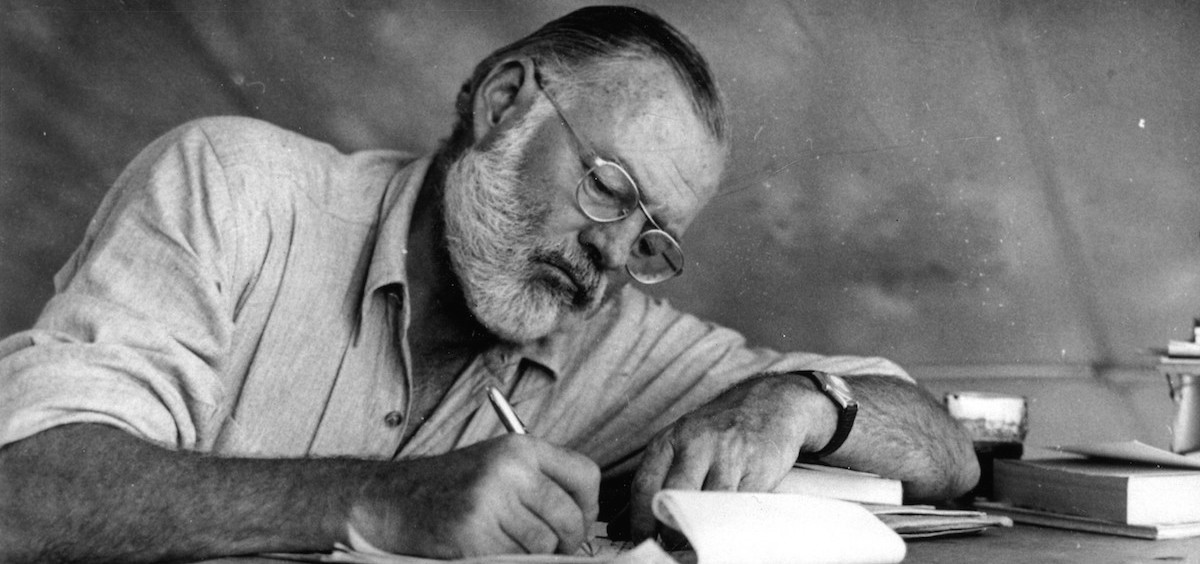

He was the larger-than-life literary icon who, in the 1930s and 1940s, was considered to be the greatest living writer of prose fiction.

He was a risk-taker with an unslakable thirst for adventure. He drove an ambulance in the Great War and was seriously wounded. He loved boxing and bullfighting and being where the action was.

And after his reputation was established with the publication of The Sun Also Rises in 1926, Ernest Hemingway became the spokesperson for the post–World War I generation of writers.

In his studies of the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement that spanned the 1920s and 1930s, Ohio University’s Gary Holcomb became interested in Hemingway’s influence on several of its writers, especially the Jamaican-American writer Claude McKay.

This work led him to ask two broader questions: Exactly what was Hemingway’s influence on black writers of this time and in the decades that followed the Harlem Renaissance? And how, conversely, did these black writers influence Hemingway?

What specifically interested Holcomb, an associate professor of African American literature in the Americas, is what he calls the “conversation,” or “inter-textuality,” that occurred between black writers and Hemingway in their fiction.

“Five years ago, I noticed that the Hemingway Society was looking for someone to do a panel at the next Modern Language Association conference, something on new directions in Hemingway studies. So I organized a section on Hemingway and black writers,” says Holcomb, who has published a book on Claude McKay’s work, as well as a dozen journal articles and book chapters on African-American writing.

The panel attracted a wide range of literary scholars, several of whom encouraged Holcomb to publish an anthology on the subject. The highly respected black literary scholar Charles Scruggs, an English professor at the University of Arizona, was particularly excited about this project, so Holcomb asked him to be co-editor.

What resulted is Hemingway and the Black Renaissance, which includes 10 essays on literary connections between Hemingway and McKay, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Toni Morrison (one of Hemingway’s more vocal critics), and others. The book will be published in March 2012 by Ohio State University Press.

Holcomb’s contribution to the collection covers McKay, the first black writer to publish a novel, Home to Harlem, that made the best-seller lists in the United States. “He wrote the first book of poetry identified with the Harlem Renaissance, a book that expressed the righteous anger of blacks living in New York,” Holcomb says. “He was the first poet acclaimed for his writing in Jamaican dialect and the first black writer to receive the Medal of the Jamaica Institute of Arts and Sciences.”

Holcomb gives a brief plot synopsis of Home to Harlem: “Jake, a young black man, joins the army in World War I, with the desire to go to Europe to fight for democracy. But he’s not permitted to fight; instead, he’s relegated to the servant class in the military and becomes so angry about this that he deserts. He travels first to Havre and then to London for a couple of years before he gets homesick and returns to Harlem.”

The first time he read McKay’s book, Holcomb was struck by various echoes from The Sun Also Rises, published two years before Home to Harlem.

“The protagonist of The Sun Also Rises, also named Jake, was, like McKay’s central character, an expatriate American in Europe. Both joined to fight in the Great War, underscoring their roles as men of action and consequence. Hemingway’s character suffers a war wound that causes him to be impotent, and so is emasculated by the war, as is McKay’s Jake, though not in a physical way.”

It’s clear that McKay admired Hemingway’s novel. In McKay’s memoir, A Long Way From Home, published in 1937, he wrote, “When Hemingway wrote The Sun Also Rises, he shot a fist in the face of the false romantic realists and said: ‘You can’t fake about life like that.’ He has most excellently quickened and enlarged my experience of social life.”

McKay and Hemingway met only once, Holcomb adds, introduced through a mutual friend, but no record exists of their conversation.

Holcomb stresses that the interchange between Hemingway’s writing and works by black authors is not unilateral—that Hemingway also was influenced by the work of Harlem Renaissance writers.

“Hemingway clearly had shared concerns and shared aesthetic approaches with many of the black writers he read,” says Holcomb. “As he was writing his first book, In Our Time, there is evidence that he was familiar with the most famous black novel of the time, Jean Toomer’s Cane, which was published in 1923 and, like Hemingway’s book, challenges the convention of the short story form.”

Later, in the 1930s and 1940s, Hemingway’s influence would be “unavoidable” for emerging black writers such as Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Ralph Ellison, Scruggs notes in his contribution to Hemingway and the Black Renaissance.

Holcomb and Scruggs invited several literary scholars to contribute essays to the forthcoming collection, including pieces that discuss the writers Langston Hughes and Toni Morrison. Not all essays in the book may agree on the connections between Hemingway and the black writers, Holcomb says, but he and Scruggs are eager to start a dialogue on the topic.

Holcomb thinks that the time is right to give a wider audience to a subject that, until recently, was buried in the scholarly archives.

“Hemingway’s public persona overshadows his literary art,” he notes. “But if you go back in the archive and look at what these writers had to say, they weren’t concerned with his persona—they were interested in his text.”

This is an excerpt of an article that will appear in the Autumn/Winter 2011 issue of Perspectives magazine, which covers the research, scholarship, and creative activity of Ohio University faculty, staff, and students.

Follow Ohio University Research News on Twitter and Facebook.