News

‘Peanuts’ still brings comfort and joy, 100 years after Charles Schulz’s birth

By: Rachel Treisman | NPR

Posted on:

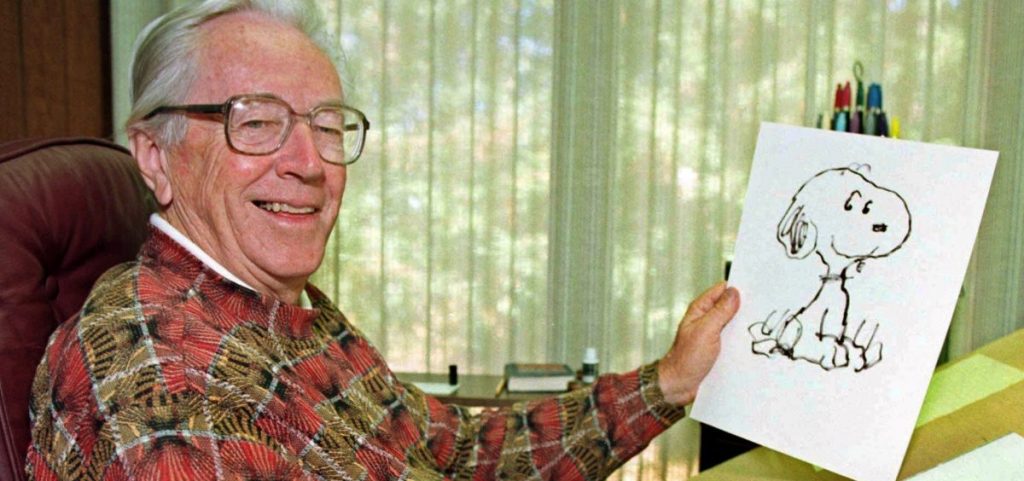

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NPR) — The man who brought us Charlie Brown, Snoopy and the whole Peanuts gang would be turning 100 today.

Cartoonist Charles Schulz died in February 2000, the night before his final comic strip ran in the Sunday paper.

But the characters he created and developed over the course of five decades still endure, in the form of reruns, beloved TV specials, a movie and a museum dedicated to Schulz’s work. So too does the comfort they provide.

That’s according to Schulz’s widow, Jeannie Schulz, and Gina Huntsinger, the director of the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, Calif. They spoke to Morning Edition about Schulz’s life and legacy, which Huntsinger calls “pervasive.”

She says he’s had a global influence, from popularizing the term “security blanket” (looking at you, Linus) to inspiring Peanuts fans from around the world to visit the museum. The most common comment she gets is that people feel comforted by revisiting something nostalgic that still makes them laugh.

Jeannie Schulz offers another explanation for the comic’s lasting and widespread appeal.

“I always say that Sparky expressed the human condition. He wrote about real emotions that kids are feeling, and it’s always delivered with a little bit of humor,” she says. “Anybody can read that strip in four seconds and get comfort from it, because it talks about humanity.”

Peanuts broke ground aesthetically and emotionally

Peanuts centers on the adventures and perspectives of children, famously tuning out any off-screen adults. And it grew out of another Schulz comic about precocious kids.

After serving in World War II, Schulz, who always wanted to be a cartoonist, started working at his alma mater, Art Instruction, Inc., on a weekly panel comic called Li’l Folks.

“One of the principals at Art Instruction Schools, where he worked as a corrector of peoples’ art lessons, said, ‘I think you should stick with the little kids,’ ” Jeannie Schulz recalls. “That’s what he turned in to all the syndicates to see if he could get a contract: Little kids, no parents.”

Schulz’s original submission to United Feature Syndicate was a panel cartoon rather than a strip, meaning it had no “definite characters,” Schulz himself recalled in a 1990 interview with NPR’s Fresh Air. When he went to New York to sign the contract he brought half a dozen strips with him, and the syndication service immediately said they’d rather go with a strip because they were easier to market.

“They said, ‘Well you’ll have to create some definite characters,’ ” Schulz remembered. “So I said, ‘Well, that’s no problem,’ because I already knew I liked to draw a little dog, and I just went home and I asked my friend Charlie Brown if I could use his name and he said that was fine. And so I created [Peppermint] Patty and Shermy and those were the four lead characters.”

The first Peanuts strip appeared in newspapers across the country in October 1950. And they weren’t like the other cartoons on the funny pages at that time, Huntsinger says.

Aesthetically, Schulz’s lines were simple and minimalistic, using only what was necessary to tell the story. And creatively, Huntsinger says, he was a genius.

“We could relate to his strip, like we could see ourselves as Charlie Brown — our kite’s stuck in a tree again or the frustration of something happening,” she says. “And also Charles Schulz was the first one to really talk about emotions in the strip, so it changed the cartooning industry … he was so different than what was on the page when he first started.”

It remains a source of comfort, even in reruns

Schulz spent a lot of time with his characters over the decades (as did the public: By 2000 Peanuts was running in more than 2,500 newspapers in 75 countries).

And he related to each of them, telling Fresh Air that he doubted it would be possible to “do something every day with a group of characters … without each one of those characters being a little bit of myself.” That’s probably why they changed in little ways over time, he added.

“I try to be consistent in their personalities but I also think that none of us is ever really consistent in the things that we do and say,” he said. “We all have our little good points and bad points; this is what the characters have.”

And while the universe he created lives on, Schulz was very clear that he didn’t want anyone reviving Peanuts after him. His syndicate contract stipulated that when he stopped drawing, the strip would stop.

Schulz himself told Fresh Air that his children were the ones who insisted on that clause, because they said “we don’t want anybody else drawing Dad’s strip.”

“I hope that no one else ever touches the strip because the strip is me,” he said.

So while plenty of artists may have wanted to fill Schulz’s shoes, Jeannie says, the Peanuts cartoons that people (herself included) see in newspapers today are all reruns.

“And what amazes me is that it’s still funny,” she says. “You still want to read it. Right now Snoopy’s going to Needles or somewhere to find Spike, and it’s just funny.”

She said that many people remember being comforted by the Peanuts crew as kids — like running home from school to shut themselves in their room with the paperbacks — and still seek comfort in them now. Huntsinger agrees.

“We’ve been listening to so many people talk around the centennial, and one of the cartoonists said, ‘You know, people are trying to sell us things all the time, like you’re supposed to be happy, you’re supposed to do this, and Charles Schulz sort of said it like it was.’ So people were like yeah, I get these characters, I feel a part of this, they speak to me.”

The interviews for this story were conducted by A Martínez, produced by Taylor Haney and edited by HJ Mai.

9(MDU1ODUxOTA3MDE2MDQwNjY2NjEyM2Q3ZA000))