News

New Kentucky Home: From Battle Zone Refugee To Business Owner

By: Becca Schimmel | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

The international refugee crisis caused by people fleeing the war-torn Middle East has been a high-profile issue in the presidential campaign.

Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton told CBS’s “Face the Nation” last year that “the U.S. has to do more” to meet what she called the worst refugee crisis since the end of WWII.

Republican opponent Donald Trump told a rally in New Hampshire that as president he would turn away refugees from nations such as Syria. “If I win, they’re going back!” he said.

But beyond the heated political rhetoric, the work of finding new homes for asylum seekers continues at a dozen refugee resettlement areas in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia. And as new new refugees arrive from Syria, those who have already made the transition to a new life in America are lending a hand.

The International Center of Kentucky, in Bowling Green, will be resettling forty Syrian refugees this month. They’ll join a community of more than 10,000 asylum seekers from around the world that the center has helped to resettle since beginning operation in 1981.

I sat down with a former refugee to better understand his journey, and how the small business he has started is creating a community of support for refugees making their new Kentucky home.

From the Middle East to the Midwest

In 2013 Wisam Asal opened Jasmine International Grocery, a small family run store with sweets, religious items and food from many countries.

Asal walks across the street wearing a baseball cap to his new restaurant, Babylon. People chat and catch up at the counter as they order shawarma and falafel sandwiches. He’s found a way to bring a bit of his home country’s culture to Kentucky and create two businesses that have quickly become important to Bowling Green’s international community.

Asal said it wasn’t easy starting a business here but the community of refugees and other people in Bowling Green helped him succeed.

“We have friends who are at the same time our customer,” Asal said. “They help us, they encourage us.”

Life During Wartime

In his native country, Iraq, Asal taught English until the U.S. war when he became a translator for the U.S. Army. The work made him and his family potential targets. Even his trips between home and work became hazardous, as kidnappers and assassins would strike translators or their loved ones during these daily routines.

“Some of my friends work as translator, interpreter has been killed or like kidnapped. Nobody has idea about them,” Asal said.

It took two years before Asal got approval to move to America through a refugee resettlement program. He packed up and moved to Bowling Green with his wife and two daughters in 2010. His son was born in 2011.

When Asal first got here there weren’t many jobs. So, like many other refugees, he worked in a chicken processing factory. He then worked as a teacher’s aide before deciding that he wanted to start his own business.

Love Of Food Becomes A Business

Asal saw a need for other refugees to get the Halal food that they were used to. Halal means food prepared in ways permissible under Islamic practices. Some were driving as far as Nashville to get Halal meats.

“They say they were suffering to get what they like or their kind of food,” Asal said.

Asal and many other refugees get halal food for their home from the Amish community. The Amish keep knives in a separate area that are used specifically to prepare halal meat.

“Some of them they make private place for Muslim people,” he said. “Even the knives and things they tell us, ‘This is for you.’”

Asal said he realizes that many Americans might not understand the lengths he and other Muslim immigrants go to for properly prepared food. “It is religion, we have to,” he said. “It is not like something small you can give up.”

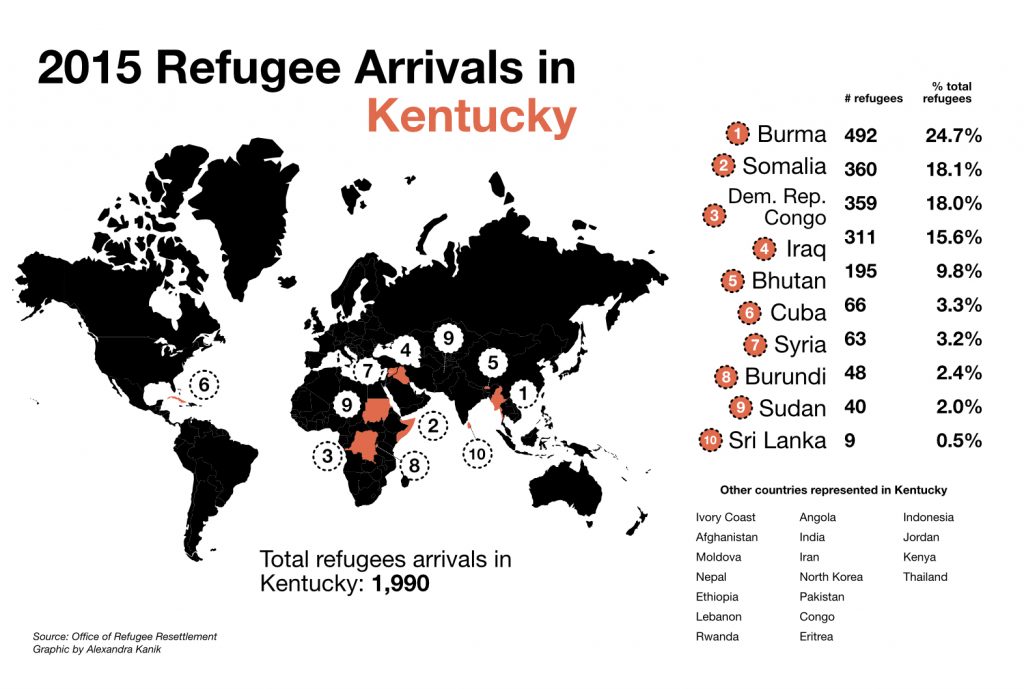

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

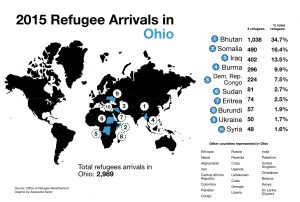

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceAsal has found food is an important part of culture and identity for new arrivals in the country. He says even many children of refugees who grow up in America still prefer to eat the way their parents do.

The grocery store isn’t just a place to buy food. It’s a place for people to keep in touch, find out whose family will be coming to America next, what events are being planned and what’s going on in the world. It’s also a place where newcomers come to get help.

“People keep coming to us asking for help, how to go to doctor, how to buy cars or things,” he said. “Even sometimes we close our business to go with them, because maybe they are refugee,” Asal said. His business has become much more.

“I call it, this is another international center. “

A Balance Of Cultures

As Asal explained his work and home life, it was clear he’s hoping to find a balance between assimilating in his new home and keeping in touch with his old one. He and his wife continue teaching their children Arabic in hopes it will help them maintain their culture. Although they prefer American cartoons, Asal encourages them to watch cartoons in Arabic.

“The TV has big effect on anyone. So we have our channels they can watch these channels and keep them learning Arabic and what is going on in our countries,” Asal said.

Some of his descriptions of parenting sound much like any other parent’s concerns. He worries that his children don’t get to roam free outside as much as they did before, when they had a large yard, and could play without being watched by their parents.

“When we grew up there it was safe for you to play outside because most people, they know each other. But here you can’t let them go out for long time, you have to watch them,” Asal said.

Although it’s different living in America Asal considers this home now and he says over time the differences between people have disappeared. He likes the people and the safety he has here.

“The people they are nice and when you ask them something they help you. They keep smiling,” Asal said.

Asal doesn’t feel homesick for his home in Iraq. Rather, when he goes back to visit he finds himself missing his home here in America.

Bowling Green, pop. 61,400, has helped to resettle some 10,000 refugees in the past 35 years. (Photo by Becca Schimmel/ Ohio Valley ReSource)