Culture

Catching Lightning In a Bottle: ‘American Epic’ Explores American Recordings

By: Emily Votaw

Posted on:

In the 1920s radio almost tanked the record business.

Record companies knew they needed to capture a new market, and they did so in an ingenious fashion.

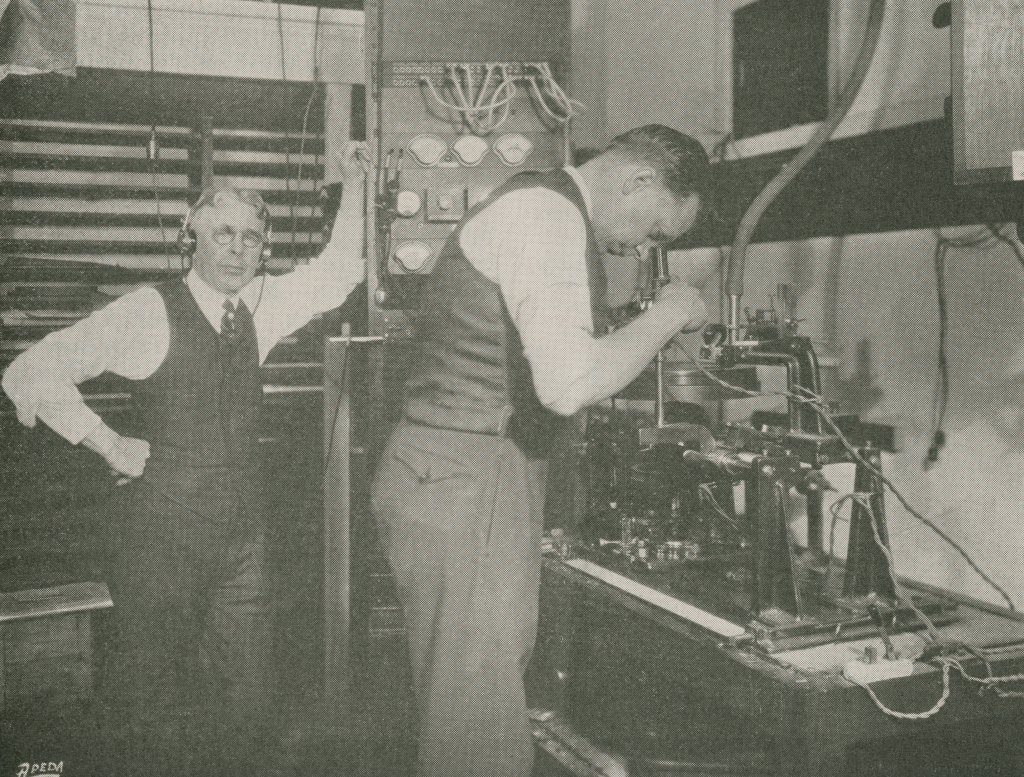

“Record companies in the ’20s began sending engineers into the ‘hinterlands’ to find new people to record; much of this was to use in what was termed ‘race’ or ‘hillbilly’ records at that time – very derogatory terms, but they were targeting people from those areas to purchase the music,” wrote Terry Douds, WOUB Public Media’s Broadcast Operations Supervisor, in an email to WOUB. “They would send a whole truckload of equipment including mics and electronic amplifiers, a weight-driven lathe to cut the master discs, a supply of the thick wax discs they used for masters, and they even sent wet cell batteries — similar to car batteries – big and heavy — because electricity wasn’t a perfect commodity in the early days – any fluctuations in the local current would have affected the recordings. They found new artists who probably would never have been recorded due to impoverished conditions and lack of abilities to travel.”

The recording lathe used to capture these sounds functioned off of a pulley system run by a series of weights that worked off a set of clockwork gears. The machine would actively press the album during the three-minute span that musicians had to record.

They referred to the process as “catching lightning in a bottle.”

Some of the most iconic American musicians were recorded this way: the Carter Family, Blind Willie Johnson, Lydia Mendoza, Elder Burch, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Robert Johnson, and many others.

Over the course of the past decade, director Bernard MacMahon, producers Allison McGourty and Duke Erikson have painstakingly assembled a documentary that pays tribute to those early American recordings. Entitled American Epic, the three-part documentary, (narrated by Robert Redford,) will be broadcast on WOUB-HB May 16, 23, and 30 at 9 p.m.

Throughout the course of the series, the earliest American recordings are artfully explored, all whilst Jack White and T Bone Burnett record 20 contemporary artists using a recording lathe built of antique parts built by engineer Nicholas Bergh. Pokey LaFarge, Alabama Shakes, The Avett Brothers, and Elton John are just a few of the acts who take part in the recording process.

The first installment of the series explores the early recordings that took place in Bristol, Tennessee in the ‘20s, the ‘big bang’ of country music, facilitated largely by Victor Talking Machine Company producer Ralph Peer. Often referred to as the “Bristol Sessions,” the recordings feature the likes of Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family, among others.

“My dad used to listen to early American recordings when I was growing up. I specifically remember a Jimmie Rodgers cassette being played. As a kid, it sounded really bizarre, and I thought it was odd for my dad to be listening to something that sounded so rough compared to contemporary recordings,” said Adam Remnant, a regional musician who released his debut solo EP, When I Was a Boy, last summer. “As I got older, I grew to appreciate Jimmie Rodgers quite a bit and the Carter Family even more. I remember checking out CDs from the local library of Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family. The library was a great way to discover this music because there’s something sort of studious about the endeavor of exploring this old music. I had a sense of educating myself on the roots of the popular music that led me back to these artists.”

Jack Wright, a documentarian and retired Ohio University film professor, crafted 1985’s The Sunny Side of Life, a film that sheds light on the legacy of the Carter Family. In order to create the film (which he did in association with Appalshop, an organization that has been facilitating the creation of media and art that explores Appalachia and rural America since 1969,) Wright got to know the Carter family intimately.

“Growing up, I didn’t know anything about the Carter family because their time had come and gone in terms of popularity on the radio,” said Wright, who grew up in Appalachia. “It wasn’t until I was in the army that I discovered the Carter Family. My roommate was from Fairfax, VA, and he introduced them to me.”

Throughout high school Wright had taken a liking to music, and by the time that he was in the military, he had already played rock ‘n’ roll, and had started to diversify his musical interests.

“In the ‘50s, when I was growing up, there was no sense of a cultural identity for Appalachian people. When you’re young, you’re looking for an identity, and when I was young, there was no such thing as being a ‘strong Appalachian person,’” said Wright. “In fact, we were discouraged from associating with the area we grew up in. My mother would always correct my language; she didn’t want me speaking in the manner that I picked up from other schoolkids. There was no such thing as embracing the culture. We were encouraged to get an education and leave the region as soon as we could.”

After serving in the Vietnam War, Wright returned to the states and bought a four-track recorder. Initially Wright was just interested in recording the rock band that he had, but before long he had started a record company, which was just about the time that Janette Carter started putting on weekly performances at the Carter Family Store in Hiltons, VA in 1979.

“I started recording some of the performers at what they would call the Fold, the Carter Family Store,” said Wright, who developed a friendship with Janette and her family. At the time, Wright was already working for Appalshop, and he found himself interested in trying to create a film about the Fold.

The film was aired on PBS upon its completion.

“Basically, Janette narrates the film because it is mostly her story, but that area, in Scott County, is just loaded with old-time music, and music really plays a huge part in people’s lives,” said Wright.

“In the ‘50s, when I was growing up, there was no sense of a cultural identity for Appalachian people. When you’re young, you’re looking for an identity, and when I was young, there was no such thing as being a ‘strong Appalachian person.’ In fact, we were discouraged from associating with the area we grew up in. My mother would always correct my language; she didn’t want me speaking in the manner that I picked up from other schoolkids. There was no such thing as embracing the culture. We were encouraged to get an education and leave the region as soon as we could.” – Jack Wright

“For (the Carter Family) music was a social activity, not a career path. Music provided entertainment for the household or community gatherings. These artists were the first popular music stars, so they were embarking on uncharted waters. I think there’s an authenticity to their work because it emerged organically, at least initially,” said Remnant. “You can hear the struggle in their voices through those old recordings, and they stand up today because the songs and performances are so good. It speaks to the power of the performance and musical ideas over the technology. Music is constantly at battle with its relationship to the technology used for production. An artist can lose the value of their work by being preoccupied with capturing an ideal production rather than a strong performance with strong musical ideas. Those early recordings were solely performance based, and artists today are still mining those recordings because they remind one of what ultimately matters musically.”