News

“Matewan” Revisited: Film Unearthed Region’s Buried Labor History

By: Jeff Young | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Thirty years ago the premiere of a small-budget, independent film had an out-sized effect on how many people in Appalachian coal country thought about their region and their past.

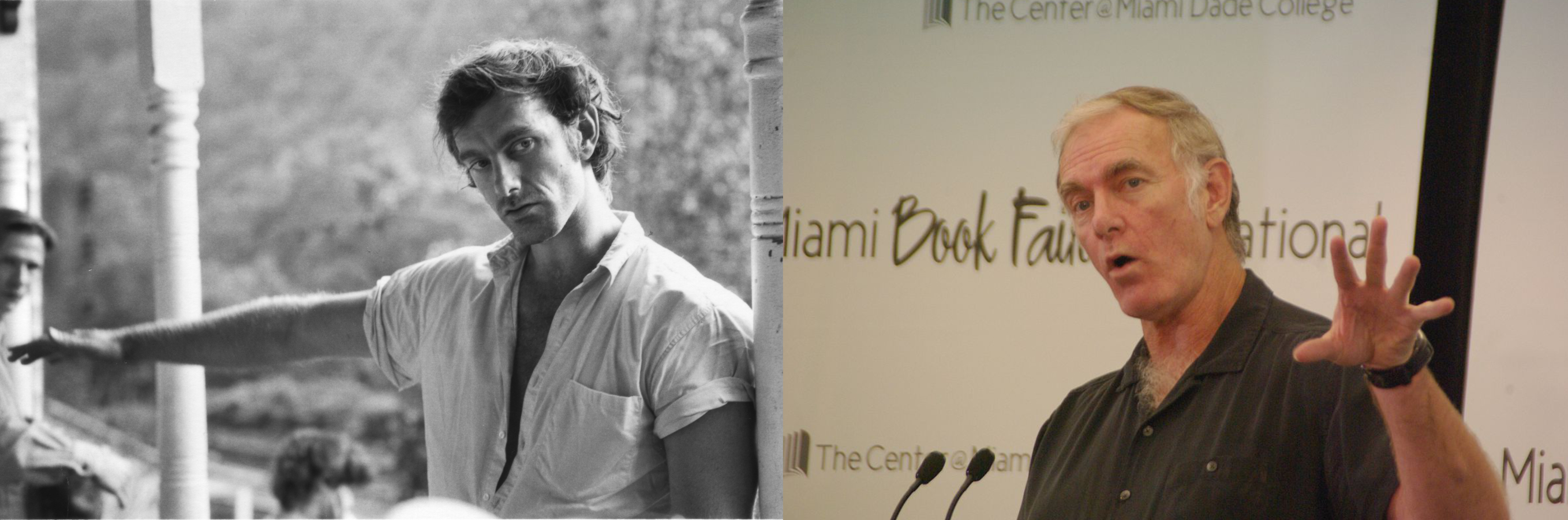

“Matewan,” directed by John Sayles, depicted a bloody chapter in the fight to organize coal miners in the 1920s, exploring themes of class struggle and pacifism in a style that evoked classic Western movies. The film earned an Academy Award nomination for its cinematography and helped establish some of its actors, including David Straithairn, Mary McDonnell and Chris Cooper.

But in the Ohio Valley region, “Matewan” is best remembered for telling a story that had long been forgotten, or, perhaps, willfully ignored. Now, a museum dedicated to what’s known as the Mine War is hosting a 30th anniversary screening of the film to recognize its role in bringing a long-buried history to light.

“It wasn’t taught”

Ask Terry Steele to introduce himself and he starts at the beginning.

“I was born in a little old town called Matewan, in the southern part of West Virginia, in 19-and- 52.”

He’s the fourth generation of Steeles to work coal in West Virginia. “Yeah, I’ve come from a long line of people mining coal.”

Steele estimates he spent 50,000 hours underground during 26 years as a miner.

“A union miner,” he corrected.

Union. It’s an important distinction for Steele. He takes great pride in his region’s role in forging the United Mine Workers of America. But he said that it’s often been a forgotten role.

“I still don’t think a lot of people know the history in the area,” he said. “It wasn’t taught in schools, and if it wasn’t taught in homes you’d have no idea of the roots of our region or how our union got started.”

It’s a common lament in the area. So much happened in the hills that produced coal and so few seem to know it.

“This one area of West Virginia history has been ignored and, in some cases, suppressed,” West Virginia Southern Community College history professor Chuck Keeney said. Keeney has documented the ways that early miners’ strikes and marches were censored from press accounts and then downplayed in history classes for decades afterward.

“They wanted to keep labor history out of the textbooks,” Keeney said. “My own family didn’t talk much about it.”

And that’s pretty striking considering Keeney’s lineage.

“I’m also the great-grandson of Frank Keeney, who was a central figure in the West Virginia mine wars,” Keeney said.

Even with that personal link to organized labor’s origin, it just wasn’t something the family focused on.

“No, it wasn’t,” Keeney chuckled. “First of all, he was charged with murder, charged with treason.”

The charges came in connection with a 1921 miners’ uprising known as the Battle of Blair Mountain, in which thousands of marching miners confronted well-armed coal company guards. Keeney’s great-grandfather was acquitted on the murder charges and treason charges were dropped. But the charges and the taint of a “socialist” ancestor made the family tree an awkward topic for conversation.

And so it went for years. Coalfield labor history was often shunned, censored, forgotten.

Then, in the mid ‘80s, a film director named John Sayles came to West Virginia to shoot a movie he’d been thinking about since a hitch-hiking trip two decades earlier.

“I think America’s labor history hasn’t been forgotten so much as buried, on purpose,” Sayles said.

A lot of Listening

“I used to do a lot of hitch-hiking in the ‘60s,” Sayles told me. “I was going through Kentucky and West Virginia during the contentious UMW election.”

That was when Joseph “Jock” Yablonski challenged UMW President Tony Boyle, and was later murdered along with his wife and daughter. Sayles said many people he talked with compared the violence to the bloody incidents from the 1920s.

“I got a lot of rides from coal miners who were kind of shaking their heads about it and they said, ‘boy it’s really bad, and I think this is going to be as bad as the Matewan massacre,’” Sayles recalled.

“I had never heard of this Matewan massacre, so it kind of led me to do some research.”

He learned that in May, 1920, the rising tension and violence between striking miners and coal operators in southern West Virginia came to a head in a shootout that left 10 people dead in Matewan.

Sayles was hooked.

“It’s an incident that stood for a lot of the labor movement at the time,” he said. “And the story had a movie-like quality of being like a Western. It ends in a shootout at high noon on Main Street.”

More than a decade would pass before Sayles could raise the money for the film he wanted to make. But once he started, he wrote, planned, and cast with a near-obsessive attention to authentic detail.

“One thing you have to do is a lot of listening,” Sayles said of his approach to movie-making. He read diaries, histories, newspapers, and talked to people in the area about the stories they’d heard from parents and grandparents.

“Some of it is rumor, some fact. They are great stories,” he said. “There’s a rhythm and feel of those stories you try to absorb into the narrative.”

In Awe

Sayles chose to shoot the film in a tiny West Virginia town, nearly a ghost town, called Thurmond, where train tracks line the only street deep in the gorge carved by the mighty New River.

“Just being in those hills every day was great. Nothing like ‘em,” he said. “But practically, shooting down in the holler, you get less light. If you are shooting days you have to budget time carefully.”

Sayles also cast many local and regional actors including a teenager from Louisville named Will Oldham.

“I was 16,” Oldham said while sitting on his porch in Louisville. Oldham played Danny Radnor, a boy preacher and union helper who (spoiler alert!) turns out to be the film’s narrator.

“I was in awe of pretty much everyone.”

Oldham is now a musician who performs under the stage name Bonnie “Prince” BIlly. As a teenager on the set in 1986 he remembered hearing local singer Hazel Dickens deliver a graveside song for a scene.

“That there were such powerful purveyors of song walking the earth,” Oldham said. “That was pretty massive, and eye opening.”

Union With a Capital “U”

Sayles had a knock-out cast. Cooper, a rising star with rugged charm, played the pacifist union organizer Joe Kenehan. Straithairn played the far-from-pacifist sheriff Sid Hatfield. And James Earl Jones was cast as a miner named “Few Clothes,” who was among the black workers brought in to break a strike but eventually side with the union.

In a powerful scene, Jones’ character arrives uninvited at a secret union meeting. He endures racial slurs in silence but angers when called a “scab.”

“One thing I wanted to do with ‘Matewan’ was to talk about union with a capital ‘U,’” Sayles said. “Not just trade unions, but the idea that to do something bigger people have to come together and get past ethnic prejudices, racial prejudices, class prejudices, and work together.”

When I asked Sayles what theme from the film he thinks is most relevant thirty years later, he returns to the racial divisions among workers.

“That’s still going on. All our stuff along the border, with the wall, is complicated by racism and economics,” he said. “And it is to the advantage of unscrupulous employers to keep people separate, to always have someone on the bottom who can’t get a job.”

Revival of Pride

Retired miner Terry Steele has another, earthier way of phrasing that same idea.

“People in power convince poor people to kick some other poor people in the ass,” he said.

Thirty years on, the film about his hometown brings up a bittersweet mix of emotions for Steele.

Mining jobs in general have sharply declined in the past three decades and union miners are even more scarce. Steele’s UMW local is now inactive — all aging retirees.

“I’m a spring chicken in that crowd,” he joked.

But people are now more aware of their history, he said, thanks in large part to Sayles’ film.

“It matters to me because it tells a story of the struggles that the miners went through, and what we had to do to have a union,” he said.

Steele volunteers at the West Virginia Mine Wars Museum in Matewan, which his wife, Wilma, and other volunteers helped to start a few years ago. Wilma Steele also credits the movie with helping people rediscover their past.

“Absolutely it did,” she said. “And I saw a revival of pride in their history, which had been missing.”

History professor Chuck Keeney, another founding board member of the museum, said many elements of that history seem all too familiar today.

“We could spend the next hour talking about similarities to the 1920s. A lot of frightening similarities: Anti-immigration, racial tensions,” he said. “People are forgetting commonalities and thinking more about their differences.”

Keeney said the period when the film came out also saw the release of some scholarly work and important historical fiction on the mine wars, notably Denise Giardina’s novel “Storming Heaven.” He views the “Matewan” premiere as a turning point.

“It was the first time people could go to the theater, in some type of communal fashion, and talk about the history,” he said. “And so it kind of allowed people to reconnect. It got people talking about it.”

One such conversation was with his father. Keeney remembered going to see the movie “Matewan” with his dad, who slowly opened up about the Keeney family history.

Today, he hopes the Mine Wars Museum will help keep the story of union miners from being buried again.