News

OU Executive’s Bonus Raises Questions About Transparency

By: David Forster

Posted on:

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB) — One thing the payment of a $100,000 bonus to an Ohio University senior executive a few months ago has made clear is that this can be done in private.

No public vote was taken, and no other public disclosure was required.

Had the university’s board of trustees signed off on the bonus, it would have required a public vote. But since the university’s interim president signed the contract, which in all other respects was a decision by the trustees, it remained private.

Because the bonus in this case originated with members of the board of trustees, it raises the question of just how far trustees can go in trying to award a bonus or other compensation without triggering a public vote.

In the private sector, corporations must disclose the compensation, including bonuses, they pay to senior executives so that shareholders can evaluate the company’s performance and practices.

For Richard Vedder, a nationally recognized expert on university finances, the answer to that question is yes.

“I think universities, particularly public universities, have an obligation to report very precisely and transparently the salaries of key employees,” he said.

Vedder is a distinguished professor of economics emeritus at Ohio University, where he has taught for more than 50 years. He said his research has found that universities nationwide have been hiring more high-level administrators and paying them more and more money, through raises in base pay, bonuses and other forms of compensation. He said that some of this spending happens with little or no public oversight.

“There has been a tendency in the last decade to disguise an increasing portion of the pay of key employees, and I think this has been done largely to reduce friction and embarrassment and controversy associated with large numbers,” he said.

The Ohio Department of Higher Education says on its website that university trustees “serve as stewards of hundreds of millions of dollars the state invests in its public system of higher education.”

But what about oversight of the trustees themselves? According to the department, “Trustees are scrutinized by the general public, the media, and the state to ensure that taxpayer dollars supporting the institutions are being managed in the most fiscally responsible manner.”

This scrutiny is challenging when it comes to actions not disclosed to the public. For example, university salaries are public records, but there is no routine disclosure of compensation, including bonuses, as is required in the private sector with publicly traded companies.

Instead, the public or the media must make a public records request for compensation information on one or more university employees. And new requests would have to be filed on a regular basis to find out if there’s been a change to an employee’s compensation, such as a raise or a bonus, since no notice is given to the public. These requests, then, amount to shots in the dark.

The $100,000 retention bonus paid in July to Deborah Shaffer, Ohio University’s senior vice president for finance and administration, shows just how easy it is for payment of a large sum of money to go unnoticed.

[Photo courtesy of Ohio University]

The university was transitioning to a new president and was facing both short-term and long-term economic challenges. In the midst of this, Wolfort didn’t want to lose the person guiding the university’s critical financial decisions and offered Shaffer a significant incentive to stay for at least another three years.

Wolfort took the retention bonus up with leadership of the board of trustees, presumably members of the board’s executive committee, who agreed that it was important to try to keep Shaffer on board.

The university’s interim president at the time did not share this view.

David Descutner was just days into his new position as Ohio University’s interim president when he was approached by two trustees at a board meeting. Descutner told WOUB News he does not recall which board meeting this was, but agreed that the timing suggests it was the meeting on Feb. 22, 2017.

The minutes from that meeting show that the board’s executive committee went into executive session and that one of the items that might have been under consideration in that session was employee compensation.

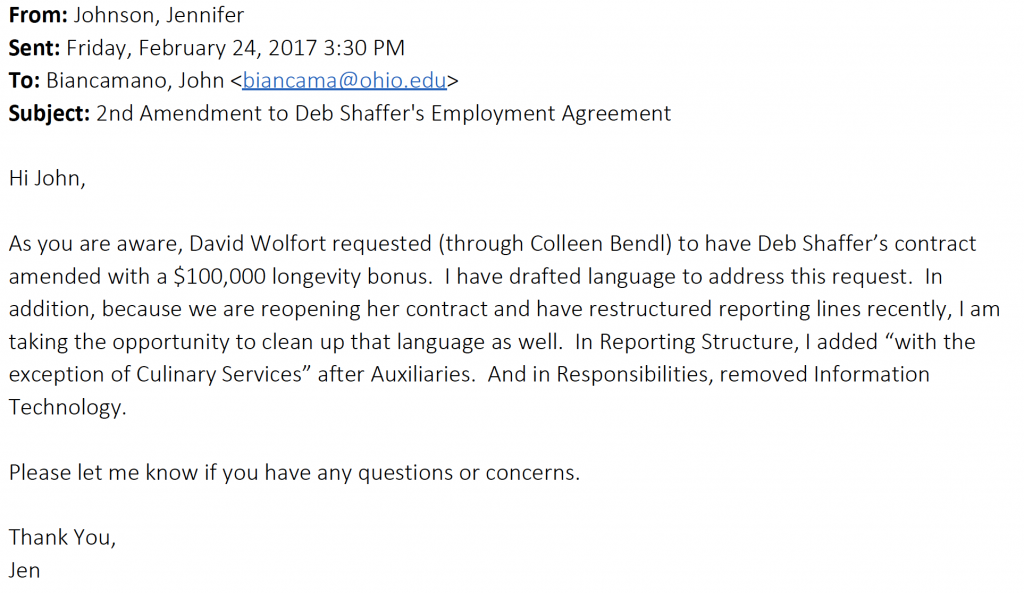

Two days after the meeting, a lawyer in the university’s legal affairs office sent an email to John Biancamano, the university’s general counsel at the time. In that email, the lawyer wrote: “As you are aware, David Wolfort requested (through Colleen Bendl) to have Deb Shaffer’s contract amended with a $100,000 longevity bonus. I have drafted language to address this request.” Bendl is the university’s chief human resource officer.

Biancamano then sent an email to Wolfort, in which he wrote: “Per your request to Colleen Bendl, I am sending you an amendment to Deb Shaffer’s contract.” Descutner was cc’d on this email.

More than two months later, on May 8, 2017, the contract formalizing Shaffer’s retention bonus was emailed to Descutner for his signature.

Descutner told WOUB News that he considered the contract a done deal and that his signature was a formality. “I believed it was my responsibility to sign it regardless of my personal views,” he said.

On May 10, 2017, two days after the contract had been sent to Descutner, his assistant emailed it back to the legal department with his signature.

The board of trustees is the ultimate decision-making authority for the university. But much of the decisions involving day-to-day operations are delegated to others. The university president has been granted the power to make decisions over compensation.

Photo courtesy of Ohio University

While decisions about compensation are typically handled by the president, the trustees do have the power to make these decisions on their own. In response to questions by WOUB News about the bylaws, the university said that “compensation decisions” would require a public vote by the board.

This raises a question: Is the decision to offer an employee a bonus and then direct the legal department to draft a contract formalizing this offer a “compensation decision” that requires a vote by the board? Or does the bonus offer not become a compensation decision until the contract is signed? In this case, the contract was signed by the university’s interim president, so if this was the compensation decision, then no vote was required.

The university’s position is that no vote was required. In an email to WOUB News, a university spokesperson wrote that “the board could have chosen to step in and take collective action on this compensation decision if, for example, the Interim President refused to sign the amendment. Since the Interim President approved the recommended compensation, there was no need for a vote by the board.”

In a letter to the Athens News published late September, Descutner said that it was not his decision to offer Shaffer a retention bonus. He said that he did not believe that her performance merited such a bonus.

Descutner’s letter came a little more than a week after the newspaper broke the story about the bonus, which it had confirmed through a public records act request for Shaffer’s employment contract.

Descutner said in his letter that the two trustees who approached him about the bonus made it clear that neither his input nor approval were being sought. Descutner said that he did not review the contract “before my electronic signature was affixed to it.” The implication is that someone else had placed his signature on the contract, but Descutner made it clear that this is not an unusual practice.

When asked for clarification, Descutner told WOUB News that he could not recall with certainty whether he signed the contract or whether someone applied his signature on his behalf. He said that in any case, he would have signed the contract because he believed it had been appropriately authorized by the trustees.

“I think universities, particularly public universities, have an obligation to report very precisely and transparently the salaries of key employees.” — Richard Vedder

Because the contract was signed by the interim president, there was no public action. And because there is no requirement that the university proactively disclose raises or bonuses offered to employees, this bonus and another $100,000 retention bonus offered to Shaffer two years later, might have remained a private matter had the Athens News not filed its public records request, perhaps in response to a tip.

Whether this matters depends on how much public scrutiny the university’s spending decisions should be subjected to. The state Board of Higher Education’s position, as stated on its website, is that the public has a significant role to play in scrutinizing how millions of taxpayer dollars are spent.

In an email to WOUB News, university spokeswoman Carly Leatherwood acknowledged that outside a formal public records request, there is no easy way to access compensation information. But this may change soon, she noted.

“Ohio University is committed to transparency,” she wrote. “We are working to develop ways to access executive compensation information outside of the public records process in the near future.”

Ohio University holds WOUB Public Media’s license to operate.