News

Prisoners And The Pandemic: A Year Into COVID, Crowded Jails Fuel Infections In Ohio Valley

By: Alana Watson | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

BOWLING GREEN, Ky. (OVR) — When the first coronavirus cases were reported last year, Warren County, Kentucky, Jailer Stephen Harmon knew there was going to be a COVID-19 outbreak in his jail. It was just a matter of when.

“We tried our best to keep it from happening,” he said. “However with this many people in a fairly small spot, we knew that that was going to happen at some point so we responded to it as best we could.”

Harmon said that only three inmates got seriously ill and two had to be hospitalized. Fortunately, the facility reported no deaths due to the outbreak and the jail has stayed COVID-free since.

“It’s been difficult because this is a congregate setting, and it is overcrowded and there is no ability to truly socially distance as being prescribed by all of the health officials,” Harmon explained.

Crowded jails are a common problem in the Ohio Valley, largely fueled by arrests related to the region’s addiction crisis. For example, the Warren County facility has 562 beds. At one point last year, 760 inmates were in the facility.

It’s been a year since the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a global pandemic, forcing all major institutions — including jails and prisons — to rapidly find ways to try to limit the spread of the virus. But some public health experts say those efforts have fallen short, and the rate of infection among incarcerated people around the Ohio Valley is far higher than that for the general public.

In Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia more than 15,000 state and federal inmates have tested positive for coronavirus and COVID-19 has claimed more than 200 lives among prisoners and staff in the three states. As outbreaks continue in some regional jails and prisons, attention now turns to the promise of vaccines, and questions about where incarcerated people will fall in the priority for receiving a shot.

COVID and Crowding

Throughout the region officials at correctional facilities mandated masks, limited social interaction, and made family visits virtual. They started testing transferred inmates and people with symptoms.

But despite the effort to reduce incarceration, some regional jailers found their inmate population increasing during the pandemic.

“There are more people in jail now than there was a year ago when the pandemic first hit. But still when someone tests positive for COVID they have to be isolated and that just takes up jail space.” Athens County, Ohio, Sheriff Rodney Smith said.

The largely rural county was hit hard by the opioid crisis and Smith said drug crime went up during the pandemic.

“If the numbers of people testing positive for COVID are down, we can put more people in the jail, but it just depends on how many people test positive,” he said. “We may have to reduce the amount of people in jail by virtue of ankle monitors or being released just to make room for these isolation cells.”

Smith said a lot is taken into consideration when trying to establish incarceration criteria.

“We put a lot of work into it and still do,” he said. “There’s always a problem with trying to find jail space.”

Positive Cases

Since the pandemic started, more than 15,000 people in prisons and jails around the Ohio Valley have tested positive for COVID-19, according to data from the COVID Prison Project, a database tracking COVID-19 in jails and prisons.

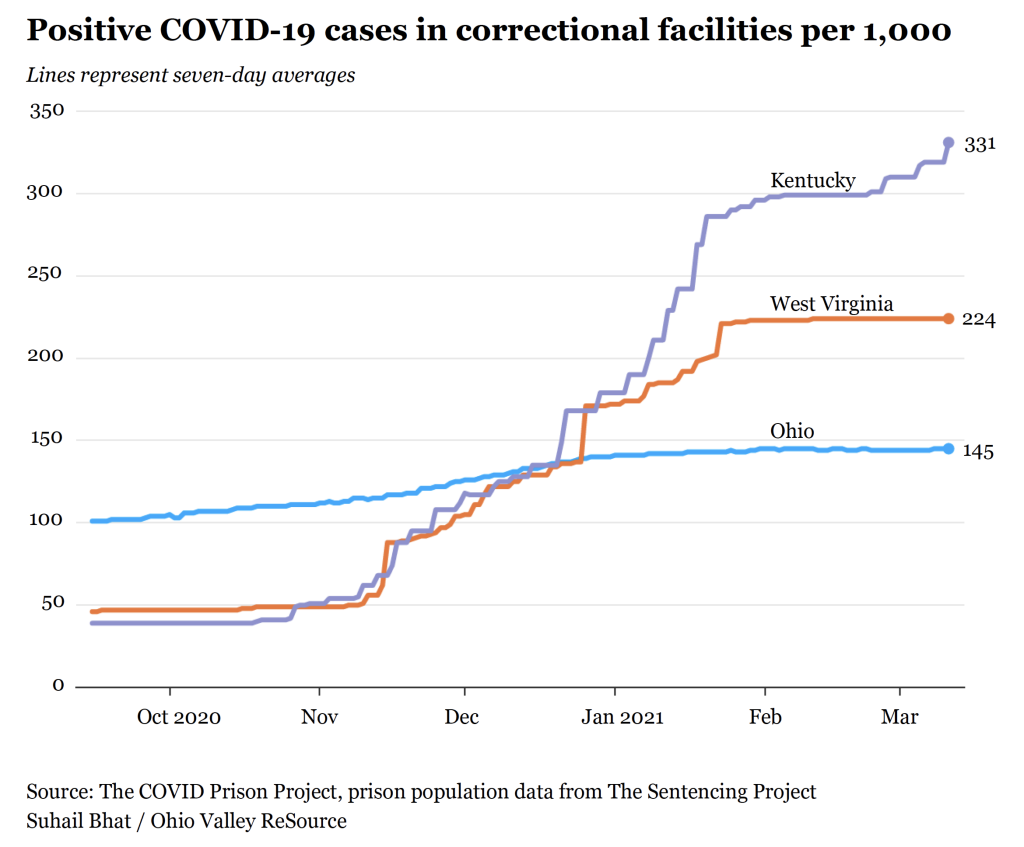

The group’s data show 7,631 inmates and 1,046 staff members in Kentucky have tested positive. The state’s infection rate among inmates was 32%. In Ohio, 7,275 inmates and 4,694 staff members have tested positive, and the infection rate among inmates is 15%. In West Virginia 1,525 inmates and 516 staff have tested positive and the state’s infection rate among inmates is 23%.

In all three states the rate of coronavirus infection among incarcerated people is far higher than the rates for the general public.

“Eleven million people in this country cycle through jails in any given year and so that same risk of bringing that exposure home is equal for staff and people who are incarcerated,” she said.

“I think some of these low hanging fruit things, like masks and testing, especially when it’s indicated when people are showing symptoms, there’s been change there and that change is important,” she said. “But I still think not nearly enough has been done in these big major ways to do things that we know work.”

Brinkley-Rubinstein believes there are two main ways to mitigate COVID in correctional facilities and to help reduce community spread: release people and vaccinate.

“To decarcerate, to have less people in crowded jails and prisons that are in close contact with each other who are spreading COVID very rapidly, and that is one thing that we haven’t seen changed much at all,” she said.

Brinkley-Rubinstein said that efforts to reduce incarceration have fallen short and now attention is turning to the promise of vaccines.

Vaccinations

According to the COVID Prison Project, the death toll among inmates so far has been close to 200 in the Ohio Valley. In West Virginia, nine inmates and two staff members died from the virus; 134 inmates and 10 staff members in Ohio have died; and in Kentucky 46 inmates and five staff members have died. In Kentucky and Ohio the death rate due to COVID-19 among prisoners is higher than for the general population in those states.

Outbreaks in prisons and jails have accounted for a large number of cases reported in some rural countries such as Lyon County, Kentucky, and Pleasants County, West Virginia.

Betsy Jividen is a commissioner for the Division of Corrections and Rehabilitation in West Virginia. She’s hoping states will soon begin prioritizing vaccinations for inmates. According to Jividen, state officials are diligently working to get vaccines distributed.

“Inmate numbers are in their metrics. And, you know if and when that time comes, we’ll be ready to do it,” she said.

Brinkley-Rubinstein said prioritizing inmate vaccinations can help get the virus under control in correctional facilities, and she said prisoners seem eager to get a shot.

“In places that have surveyed people who are incarcerated and asked if they’d be willing to take it, we see much higher rates of acceptance then we might imagine,” she said. “And I think that’s for a number of reasons.”

Those reasons include the desire to have family visits again, and to alleviate the increased confinement due to COVID safety precautions.

So far, Ohio Valley states have offered vaccines to correctional facility staff, but not most inmates. Medically vulnerable inmates in Ohio have been offered vaccinations. Officials in Kentucky and West Virginia have not yet released plans to vaccinate inmates.

When a decision is made, Kentucky jailer Stephen Harmon is hoping the Johnson & Johnson vaccine will be the one for them.

“It is a one-shot system,” he said. “Oftentimes, folks that are in custody, unless they are a state or federal inmate you may not have them in 21 days and a lot of times getting information to them once they’ve left is difficult.”

A recent surge in coronavirus cases in Kentucky’s Lyon County shows just how vulnerable incarcerated settings are. State officials said a spike in COVID cases there is associated with an outbreak in a prison. Lyon County is currently the only western Kentucky county where community spread is still at a critical level.

The Ohio Valley ReSource gets support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and our partner stations.