Culture

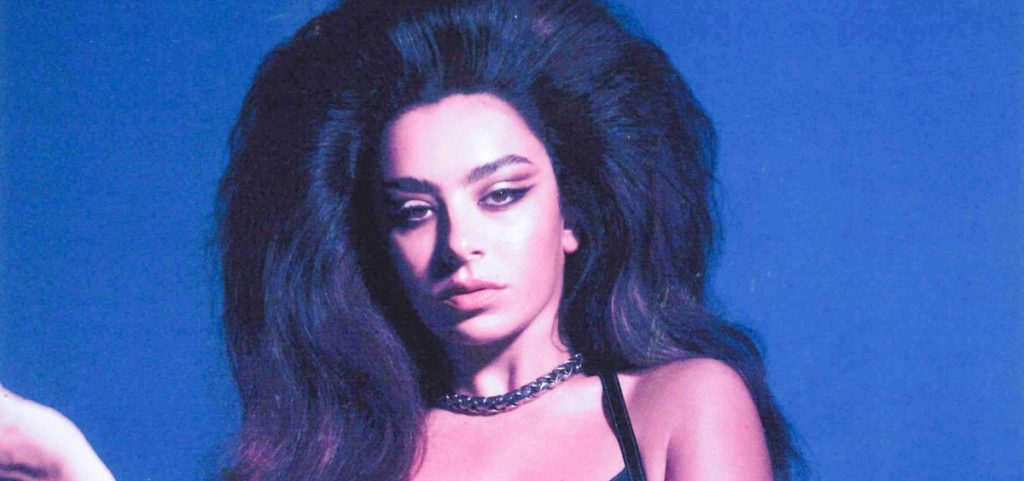

‘I love selling out’: Charli XCX on the volatile pop of ‘Crash’

By: Reanna Cruz | NPR

Posted on:

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NPR) — Throughout her career, Charli XCX has always straddled the fence between two realities: that of mega, stadium-filling stardom, and a relatively “if you know you know” career, fueled by a devoted cult following of fans dedicated to making her vision of a pop-propelled future a well-kept secret.

Now, she’s trying her hardest to bridge the gap between the two. Charli XCX’s latest album, Crash, out March 18, is a 34-minute primer of pop music at its most fundamental. Through 12 tracks, the English singer-songwriter bobs and weaves through almost four decades of chart-topping sounds, from the Wham!-esque gated reverb of the ’80s to the disco revival of the 2020s — setting herself up as a pop star who can stand alongside the greats: Janet, Madonna and Britney among them.

It’s a turn that may come as a surprise to fans. The past few years have found Charli XCX becoming a pioneer of the hyperpop sound — though she bristles at the term. She gained notoriety for her mixtapes that brought together fellow artists and producers experimenting in pop for whirlwinds of musical potential; even her last album, how i’m feeling now, was a project that distilled the Charli XCX sound down to its bare essentials, but still kept her raw, cutting-edge creativity at the center.

Crash is cutting-edge for her too, but in a different way: On this record, her last for Atlantic Records, she leans fully into a mainstream pop persona for the first time in almost a decade, creating an album built around the concept of, in her words, playing “the game.” What if she conformed to the traditional idea of being a “major label pop star”? What would that even look like? To Charli XCX, it’s becoming the most vampiric form of herself, adopting a persona that draws upon years of pop pretense and embraces something that some before her would never admit to doing: selling out.

The album indicates a radical turn in perspective for Charli XCX, who has shifted her sights from boundary-pushing sounds to commercial pop — for the moment, anyway. Maybe she’s scared — this is her last album on the major label she has been signed to since she was a teenager, after all. But on the other hand, maybe her mindset making Crash is indicative of a larger shift in Charli XCX’s career: one that finds her comfortable enough in her artistry to finally take control of her own narrative, and carve out a path to pop ubiquity that she’s long wanted to achieve.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Reanna Cruz, NPR Music: I want to talk about the overall imagery of the album. The rollout tended to skew very dark, with Instagram pictures of cars on fire, the whole “selling your soul” bit; I’ve heard some talk about the [1996 David] Cronenberg film Crash being a reference. What were your aesthetic inspirations coming into the album?

Charli XCX: Referencing Cronenberg is unavoidable when the album is called Crash. To be honest, I was into a lot of self referencing for this album, which was part of the reason why I called it Crash. I’ve had so much constant narrative around cars in my lyrics and videos. I think, without sounding too much like a narcissist, I was touching on a lot of my own reference points for this album and playing into the idea of what a stereotypical pop star is often deemed to be, and looking at the boxes women are often put in — the virgin, the whore or the vixen — and kind of exploring what those themes are within pop music, and the way that the music industry can sometimes perceive women and characterize them.

Generally speaking, in the eyes of the media, it’s sometimes impossible for them to see women as multiple versions of these characters. It’s often just like they can be one thing and not another thing. For this album, I was exploring the idea of what the most sexualized, heightened, vampiric version of myself could be. And I think that also plays into the “selling your soul” narrative [and] danger — it’s very volatile, the image of this album. I think some people are really turned off by it, which is quite interesting, and some people love it. It’s heightened sex, sexiness — that’s where I was at. And I think that does relate back to Cronenberg’s Crash because that book and that movie is about these people who want and feed off their favorite thing and will go to any length to feel this sexuality and connection.

You’ve called this album sort of a performance art piece in previous interviews. Is that performance art piece that sort of hypersexualized, video vixen type?

I want to say it can be interpreted that way if you want to interpret it that way. But I’ve always said as well that this album is a great pop album. In my eyes, I have not sacrificed any kind of sonic elements in order to make this performance art statement or whatever. The music is really good. And if you want to just put it on and listen to it as a great pop album with a variety of different styles of songwriting, more traditional versus more left, you can do that. But I would say, if you want to get theoretical about it — which I feel some of my fans like to do [laughs] — I would say the commentary is actually based more around my history within the music industry and the fact that I’ve been signed to a major label since I was 16 years old. Throughout that time, I’ve never really utilized the major label in the way that I am supposed to. I’ve kind of always gone off grid, made my own path.

There’s been quite a lot of tension between the way I’ve chosen to do things and the way a major label expects female pop artists to do things. And I think a lot of my previous work has really been born out of that tension — or some, at least. With this final album, the final album in my deal, I wanted to play into this idea of, “What if I played the game?” Hence the whole selling my soul thing. What if I took pitch songs? What if I worked with an A&R for the first time in 10 years? What if I started using interpolations in a few of the songs? That’s the world. To be honest, yeah, it could be deemed a performance art piece, but it’s also a personal test to see whether I can handle it and whether that makes me happy and how it makes me feel. I’d say that’s more the performative element of it. And with that comes all of the stereotypes of major label pop star[s], which I think are definitely changing now when you look at the frontier of female pop. I think more than ever there’s a lot of variety. But I also do think that the narrative of boxing in female artists is still very much present. It’s just dressed up a little bit differently.

Toying with this concept of selling out, how do you as a pop artist feel about selling out? Is that still a problem for artists? Do you think the culture has shifted?

Oh, I love selling out. Yeah, I don’t care, because the thing is I actually find it fun and interesting. Pop is supposed to be a fantasy, right? I feel that sometimes people are so caught up in this idea of being real and authentic, particularly now. I feel like now it’s almost a necessity for the validity of an artist for them to be considered real or genuine or down to earth. You know, “Well, she’s a real artist because she writes her own songs.” All this stuff which feels very sort of Bob Dylan to me, which I don’t really care about personally. And maybe it’s easy for me to say this because I do write my own songs and I write songs for other artists, and I’ve definitely had that narrative surrounding me: “Oh, she can write a song, she is authentic.” I hate saying that about myself, but I feel comfortable to toy with the idea of being the complete opposite because I know that I have the receipts.

Everybody seems to be on this quest for authenticity to prove that they are real, they are down to Earth, but I personally don’t care about that in my favorite pop artists. I don’t want to know what Britney was having for breakfast, I want to see Britney in full Britney mode, being a pop star. I don’t care if that comes with this Paris Hilton-esque air of fantasy, which I think sometimes can be deemed as selling out. Selling out creates pop culture. To get Warhol-y about it, that’s what that is — it’s mass market selling out. I think it’s pop-tastic and fun and disposable. We’re in this disposable culture now more than ever so I’m kind of here for it.

I read that your inspirations [for this album] included Janet Jackson, and that sort of Janet, Madonna, one name-r culture is very unattainable.

Great pop stars have a godlike, untouchable status to them. That’s what wields a lot of power and I enjoy that. I’ve never met Madonna, but I don’t want to meet Madonna and her be like, “Hey, do you want to go for brunch?” I want Madonna c**** as f*** and Madonna. You know?

I totally get it.

That was no shade to Madonna. She’s an icon.

No shade. But I get what you’re saying, and I really see that through a lot of the record. One particular thing you touched upon is the interpolations. What made you decide to use something like [September’s] “Cry For You” or [Robin S.’s] “Show Me Love“?

The interpolation thing came from this idea of what does a stereotypical quote-unquote major label album look like in 2022? I feel like right now because of TikTok and because of this need for familiarity and because of this mass competition to be streamed, that is interpolations. People use interpolations to get a leg up on this familiarity thing with an audience. And I was interested in doing it because I felt it was a part of me doing an album in this major label space. With the Robin S. thing, [“Used to Know Me”] was a song that I had written in the pandemic and it actually sounded originally really different. But then I kept just singing that bass line [from “Show Me Love”] over the song. I was like, “Wait, this fits. It works perfectly.” And so I told my A&R, who I’ve been working with for the duration of this album, that I want to do that. And he was like, “Oh my god, amazing.” You know, gagging for it. So I was like, “Great, let’s do it.” That song’s one of those timeless songs that is always in clubs, in playlists, constantly.

You’ve made really challenging pop music, like [the EP] Vroom Vroom and your more quote-unquote hyperpop stuff, however you feel about that term. And then your massive radio hits — “Boom Clap,” “Beg for You.” Musically, where are you more comfortable? In the experimental spaces, or more in traditional pop music?

I still don’t have the answer. I think the thing that I love about this album is I feel like I have hybrid-ed the two in the most successful way thus far. You know, gun to head, do I feel more alive playing “Vroom Vroom” or “Boom Clap“? Obviously “Vroom Vroom.” You don’t even need the gun.

What I began to feel was I needed to do something unexpected. I felt that if I had made another album that was wholeheartedly going down this road of, as you say, [a] hyperpop sound, I just feel like it wouldn’t have been very challenging. Not only for me, but also for my audience who I feel like do expect me to challenge them. And I think now that hyperpop has become hyperpop, a genre where people can bracket a lot of artists with familiar sounds in one group, it feels less exciting to me to play within that space. I need to find what’s next for me. What is the sound that can’t quite be categorized, you know?

I’ve loved pop music. I grew up listening to the Spice Girls and Britney Spears. I will always love pop music. Some of the big songs that I’ve written for other artists that are very classically pop like “Señorita” [performed by Shawn Mendes and Camila Cabello] or “Same Old Love” [performed by Selena Gomez], I love those songs because they’re really classic, amazing melodies. But then I love “Vroom Vroom” because I know that’s a song that nobody else could do.

In the future, what sort of musical path will you find yourself on? Will you return to hyperpop or keep this traditional pop sound?

Even with my hyperpop — sorry, I really struggle with that [term], I get it, it’s easier [to use] …

It’s easier. I don’t like the term either. I don’t know what else to call it.

Even with that world, the melodies are still very pop. I think I’ll always write pop music. In terms of where I go next, honestly, I don’t really know until I’m in the moment. It also depends on the business end stuff for me. My record deal is up — I don’t know where I’m going, what I’m doing. That really can affect a lot of things as well. But I think I need to go back into the studio for a while and explore with people who I’ve worked with for a long time, whether that be Ariel Rechtshaid or A.G. [Cook]. I need to just be able to be free for a while with them.

You mentioned the “Angels” and being this unattainable pop star. The Angels are sort of this cult fanbase that you’ve built. As a musician with a cult following, how does it feel when it comes to your sense of boundaries with your fans?

It’s hard because I am so aware [of] how much they have given me and helped me and supported me. They were there for me at a time when I really did quite a drastic pivot within my music from “Boom Clap” to “Vroom Vroom.” Those of them who got it really stuck by me. And that’s amazing, but at the same time, I’m Charli XCX. I make music for myself, not for anybody else.

And they know that. That’s why they are my fans: they like my drama, my b****iness, my stubbornness, my life, whatever. They do! That’s part of it. Sometimes there’s tension, but I feel the tension only brings us closer. Going from an album like how i’m feeling now, where they were so involved, to an album like Crash which was made in completely the opposite way, it’s interesting, the contrast between the two. And maybe there’s some sort of grappling with ownership, when we bonded so much on a very collaborative album to when I went off and totally made [one] completely on my own. I don’t quite know the answer, but I’m working on the boundaries thing, but I also love [my fans] and know that I wouldn’t be here without them. It’s a dual thing.

Do you think, overall in pop music, should fans have a say over the career of an artist? Or do you think those should be separate?

I think it’s absolutely naïve to expect fans or people to not have an opinion or to not share their opinion, because obviously that’s what social media is for. When it comes to fandom and [having a] fanbase, there is a community of people who are uniting around one person who makes art. The common denominator in the conversations between the fanbase, some of which might live in France, Brazil, Australia, wherever; amongst all these different languages and different cultures within the fanbase, the one common thing is the person that they’re stanning. And to have a voice in the fanbase is to connect, to communicate. Often, it can start with opinions about the artists or the decisions in the music, the career. Sometimes those are good things, sometimes those are bad things. Do I think artists need to listen? No, not at all. Have I, in the past, listened and felt like I was doing something wrong? Yes, because I’m human. But do I know that actually I need to do my own thing and my gut instinct has got me this far for the entirety of my life? Yes.

9(MDU1ODUxOTA3MDE2MDQwNjY2NjEyM2Q3ZA000))