News

Historian solves a mystery involving World War II soldier from Meigs County who was missing in action

By: David Forster

Posted on:

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB) — On May 25, 1944, Worley Jacks enlisted in the United States Army.

Ten months later, he was on a frigid battlefield in eastern France, part of a unit that would soon press into Germany and help in the liberation of the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau.

Worley was 22 years old, born and raised in the area around Rutland, a small village in Meigs County where his family had lived for generations.

His great-grandfather Levi Jacks had fought for the Union in the Civil War.

A year before Worley joined the Army, his younger brother Robert Ray Jacks had enlisted in the Navy.

“And Worley wouldn’t had to have gone, but Ray had always felt that he went in because Ray did and big brother (didn’t want to be) left behind,” said Larry Rupe, whose mother was one of Worley’s sisters. “My uncle Ray, he would tear up when he talked about it because he was responsible for Worley making the decision to go.”

It’s possible Worley believed the Army wouldn’t take him if it knew about his family.

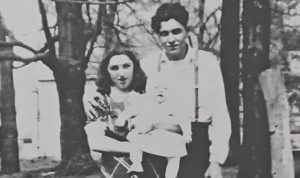

Worley had married Lillie Foley in April 1941. Their first son, Richard, was born a little over a year later. Their second son, Virgil, was four months old when Worley enlisted.

And by the time Worley was deployed to that battlefield in France, Lillie was pregnant with their third child, a girl.

She was born in July 1945, nearly two months to the day after the German surrender that marked the end of the war in Europe.

The girl was named after her father, who on March 7 was seriously injured in battle and never seen again.

“My mom actually told me that … he came to her in a dream and told her to name me Worletta,” said Worley’s daughter, Worletta Eckard.

Worletta and her brothers grew up knowing little about their father, including whether he was dead or alive. No one knew for sure. His body wasn’t found in the multiple sweeps of the battlefield after the war.

Marvel Lane, one of Worley’s several brothers and sisters, and the only one still alive, was 5 when he went off to war.

“The only thing I can remember, that my mom told me that my dad was crying a lot,” she said. “She could hear him praying outside. We had a grapevine and he would go up there and pray for my brother.”

Lillie Jacks remarried two years after the war. Worletta said her mom didn’t talk much about her father.

“For us it’s really hard to remember because mom was … still hurting even though she remarried,” Worletta said. “It’s still there, you know?”

Worletta recalls a time when she was 12 or 13 and babysitting at a family’s house. They had a record player and an album of military songs.

“I loved all the service songs,” she said. “And I was playing it that day when she come in and she started crying … so I couldn’t play them anymore. She was very, very upset about it.”

Lillie died in November 1999, never knowing for certain what happened to Worley.

But now, we know. Several weeks ago, a unit of the U.S. Defense Department announced that it had finally pieced together the whole story.

Eric Klinek is a historian with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. Part of his job is to figure out what happened to members of the military who are declared missing in action.

Each file typically contains information about where the remains were recovered, skeletal and dental charts, height and stature estimates and any material evidence found with the remains.

Klinek was looking at remains from the area around Reipertswiller in France, which is close to the German border. In January 1945, the German army launched a devastating offensive there and forced the Americans to withdraw.

In mid-February, soldiers with the U.S. Army’s 42nd Infantry Division began moving into the area to push the Germans back and advance into Germany. A major offensive was planned for mid-March, but leading up to that American soldiers went out on limited patrols. Worley was on one of those.

“It was March 7, 1945, at 3 o’clock in the morning when his patrol left their lines,” Klinek said. “They came upon German soldiers in a defensive position who immediately opened fire.”

Worley was struck by shrapnel and seriously wounded.

“They were unable to reach him due to the ferocity of the enemy fire … and that’s the last they saw of him,” Klinek said.

Several years later, remains were being removed from a German military cemetery next to where a field hospital had been located during the war. One set of remains was found wearing Worley’s dog tags.

The remains were turned over to American investigators. They concluded it was not Worley. The height estimate for the remains was 5 inches taller, and they couldn’t explain why his body would have turned up in a German cemetery near Ludwigswinkel, 14 miles from where he was last seen.

Plus, no other Americans were found in the cemetery.

The remains were marked X-8515. And for the next 70 years, Worley remained missing in action.

This matched the description of the X-8515 remains. And Klinek had an explanation for how Worley could end up so far from the battlefield. Soldiers from Worley’s patrol also reported seeing German medics on the scene as they retreated.

“We’ve seen other cases where medics have provided aid and saved American soldiers’ lives,” Klinek said, “so there was no reason to think that wouldn’t be the case here.”

Klinek requested another height estimate, which came in 5 inches shorter than the first one, and close to Worley’s height.

This was enough to get the remains disterred from a military cemetery in France and shipped to the United States. DNA analysis confirmed Klinek’s suspicion: The remains were Worley Jacks.

Worley’s remains will be turned over to his children, and a funeral service is planned for Saturday.

Klinek acknowledged that given the atrocities committed by the Nazis, and given the Germans knew they were losing the war by March 1945, it might come as a surprise that a seriously injured American soldier was transported miles to a field hospital, where medics amputated his leg in an effort to save his life.

“Just as often as you see and read about horrendous atrocities on a massive scale you see these small acts of humanity and kindness,” he said, “and I guess it kind of restores your faith in humanity a little bit.”