Communiqué

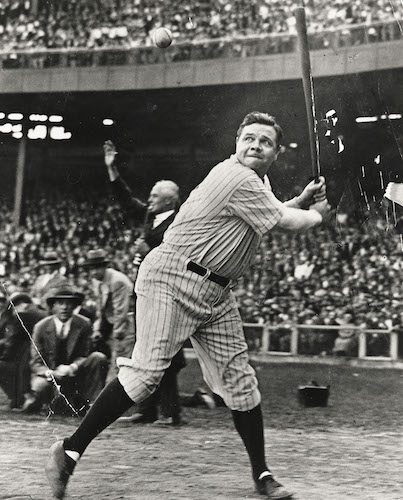

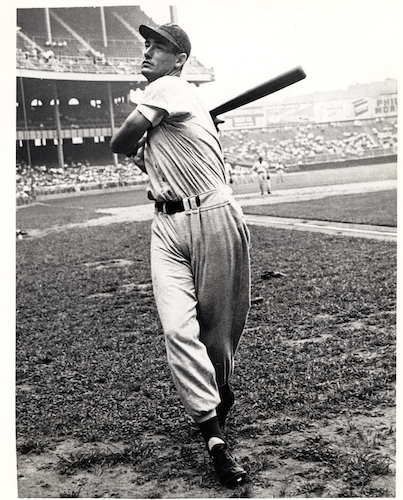

Batter Up! Ken Burns “Baseball” Returns to WOUB Thursdays, Starting March 16 at 9 pm

< < Back to batter-up-ken-burns-baseball-returns-to-woub-thursdays-starting-march-18-at-9-pmKen Burns Classic 1994 Series on the History of Baseball Returns

Thursdays Starting March 16 at 9:00 pm

Part One: March 16, 9 pm

“Our Game”

The first inning tells the story of baseball’s rise, in only one generatio n, from a gentleman’s hobby to a national sport played and watched by mill ions. Viewers meet the first baseball magnate, Albert Goodwill Spalding; e xplore the game’s first gambling scandal; see thefirst attempts by women to play the game in the 1860’s; witness the first attempt by ball players to unionize; and learn how the first black professionals were hounded out of the game in the “Jim Crow” 1880’s.

In 1909, a man named Charles Hercules Ebbets began secretly buying up adjacent parcels of land in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, including the site of a garbage dump called Pigtown because of the pigs that once ate their fill there and the stench that still filled the air. He hoped eventually to build a permanent home for the lackluster baseball team he had once worked for and now owned. The team was called the Trolley Dodgers, or just the Dodgers, after the way their devoted fans negotiated Brooklyn’s busy streets.

In 1912, construction began. By the time it was completed a year later, Pigtown had been transformed into Ebbets Field — baseball’s newest shrine, where some of the game’s greatest drama would take place. In the years to come, Dodger fans would see more bad times than good, but hardly care, listen to the southern cadences of a pioneer broadcaster, and witness first-hand baseball’s finest moment — when a black man wearing the number 42 trotted out to first base.

In 1955, after more than four decades of frustration, Brooklyn would finally win a world championship, only to know, two years later, the ultimate heartbreak, as their team moved to a new city, 3,000 miles away, leaving an empty shell in Flatbush that eventually became an apartment building, and an even emptier spot in the soul of every Brooklyn fan.

Several years ago, as documentary filmmakers engaged in trying to evoke America’s most defining moment, the Civil War, for the widest possible audience, we became aware of what a powerful metaphor the game of baseball also represented for all Americans on nearly every level. After more than four years of work we produced an eighteen-and-a-half-hour filmed history of the game for public television, and, as the arc of the life of Ebbets field, which opens our film, suggests, our interest in this game has gone well beyond a round-up of baseball highlights.

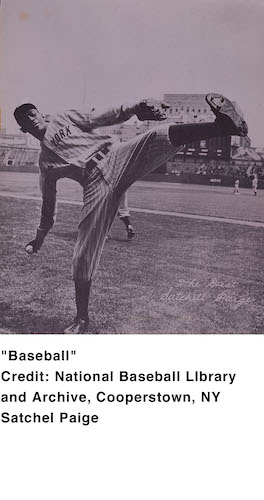

We divided our story into nine chronological chapters, or innings, and insisted as much as possible that the past speak for itself through contemporaneous photographs, drawings, paintings, lithographs, newsreels, and chorus of first-person voices read by distinguished actors and writers. We dissected the ballet of baseball with special cameras that ran at 500 frames a second (instead of 24); interviewed on-camera nearly ninety writers, historians, fans, players and managers: employed the services of twenty-one scholars and more than two dozen patient and talented film editors, delighted in getting to know one of the most remarkable men the game or this country has ever produced, Buck O’Neil; filmed for weeks with the gentle and generous people at the archives of the National Baseball Hall of Fame; and hovered for hours above ancient diamonds in Iowa, West Texas, South Carolina, and a particularly beautiful old park built in a marshy area of Boston called the Fens.

“Baseball,” the poet Donald Hall told us in a filmed interview, “because of its continuity over the space of America and the time of America, is a place where memory gathers.” It was our intention to pursue the game — and its memories and myths — across the expanse of American history. We quickly developed an abiding conviction that the game of baseball offered a unique prism through which one could see refracted much more than the history of games won and lost, teams rising and falling, rookies arriving and veterans saying farewell. The story of baseball is also the story of race in America, of immigration and assimilation; of the struggle between labor and management, of popular culture and advertising, of myth and the nature of heroes, villains, and buffoons; of the role of women and class and wealth in our society. The game is a repository of age-old American verities, of standards against which we continually measure ourselves, and yet at the same time a mirror of the present moment in our modern culture — including all of our most contemporary failings.

But we were hardly prepared for the complex emotions the game summoned up. The accumulated stories and biographies, life-lessons and tragedies, dramatic moments and classic confrontations that we encountered daily began to suggest even more compelling themes. As Jacques Barzun has written, “Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball.”

The historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., has remarked that we suffer today from “too much pluribus and not enough unum.” Few things survive in these cynical days to remind us of the Union from which so many of our personal and collective blessings flow, and it is hard not to wonder, in an age when the present moment consumes and overshadows all else — our bright past and our dim unknown future — what finally does endure? What encodes and stores the genetic material of our civilization — passing down to the next generation the best of us, what we hope will mutate into betterness for our children and our posterity? Baseball provides one answer. Nothing in our daily life offers more of the comfort of continuity, the generational connection of belonging to a vast and complicated American family, the powerful sense of home, the freedom from time’s constraints, and the great gift of accumulated memory than does our National Pastime.