News

Drowning In Milk: Dairy Farmers Look For Lifelines In Flooded Market

By: Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

LaRue County, Kentucky, dairy farmer Gary Rock sits in his milking parlor, overlooking what is left of his 95 cow operation.

“Three hundred years of history is something that a lot of people in our country cannot even talk about,” Rock said.

That’s how long the farm has been in his family. While the land has turned out tobacco, soybeans and other crops over the years, since 1980 dairy has nourished the family in and out of tragedy.

“In 2013, we had an F2 tornado that totally destroyed all the facilities here except the one we are sitting in, which is the milk parlor itself,” Rock said. If that had been lost, he said, he would not have rebuilt.

“I told myself, I’m not going to force this to happen. If a brick wall occurs, I’m going to end it.”

Instead, things moved forward with help from his community.

“Before the tornado, we had a freestyle barn. It was low, it was not well-ventilated. After the tornado, we put in a pack barn which eliminated 90 percent of the health problems I had with cattle.”

Rock said the changes ended up helping his operation significantly. But within weeks of the farm’s return to production another tragedy hit. Rock lost his legs in a tractor accident. Still, the dairy provided, and this time with more than an income.

“It enabled me to find life again in a profession that I already knew,” he said. “So, that was a driving force for me.”

Now, the farm looks to weather its greatest storm yet: a disastrous drop in revenue.

“To give you an illustration, the same farm on the same number of cows is selling a $170,000 less of product in value,” Rock explained. “So, try to comprehend having to cut your pay scale in half and see what you’ve got to do to survive.”

This isn’t a Rock family problem, this is a dairy industry problem. Prices have plummeted in a market flooded with supply from foreign producers and larger operations squeezing out small farmers. The crisis has dairy farmers rethinking the U.S. market system and looking to other countries as models for a solution.

In the Ohio Valley the effects have come swiftly. In February, more than a hundred producers across Kentucky, Ohio and five other states learned that Dean Foods, a major buyer, would cancel contracts. Another processor, Prairie Farms, will close its fluid milk processing plant in west Kentucky in June.

“It looks to me that this will be the last month-and-a-half of milking that I’ll do,” Rock said. “This is the brick wall I never faced.”

Facing Bankruptcy

The National Family Farm Coalition says the average price of milk is around 30 percent below the cost of production. Things are so bad that dairy producers that do have contracts report that co-ops are attaching suicide prevention information with their checks.

Farm Aid Communication Director Jennifer Fahy said the tough times remind her of the 1980 farm crisis, when as many as 2,100 farms would close in a week.

“We are hearing from farmers who are being referred by organizations that are usually referrals for us,” she said. “Over the years since the farm crisis the network of support for farmers has been just chipped away.”

Fahy explained that they’ve seen net farm income take a 50 percent drop and dairy is getting hit the hardest.

“Sometimes the best-case scenario is helping a farmer to navigate declaring bankruptcy and getting out before it’s even worse, unfortunately,” Fahy said.

The U.S. open market system is pushing milk production to larger farms. In 1987 half of all dairy cows were on farms with 80 or fewer cows, similar in size to Gary Rock’s operation. By 2012, that midpoint herd size was 900 cows.

Blame Canada!

International trade issues are magnifying problems for the small farms left. International Dairy Foods Association President Michael Dykes blames Canada for violating trade laws.

Dykes claimed that some of Canada’s products are being “dumped” at unfair prices due to Canada’s system of price controls, known as “Class 7,” implemented last year.

Dykes said this all stems from an increased demand in butter. Instead of importing to meet their additional butter needs, Canada raised the milk quotas that Canadian farmers can produce.

“They increased it almost 6 percent, whereas the U.S. is increasing at about one-and-a-half percent per year,” he said.

As Canada upped its quota for domestically-produced milk to make more butter, it was left with an excess supply of other products, such as skim milk powders, for which there was lower demand.

“Now you have the Canadians coming in, they are selling skim milk powders on the ground in Mexico at three-cents-a-pound cheaper than we can from the U.S. to Mexico,” Dykes said.

Dykes said the Canadian policy lowers prices on milk ingredients like skim milk powders and encourages substitution of domestic Canadian dairy in place of products they might import from the U.S.

“So we are in a situation where we have more milk right now than we have demand and that also says trade becomes extremely important,” Dykes said.

He wants Canada to open its market to more U.S. dairy. He’d like to see NAFTA renegotiated or for the U.S. to rejoin the Trans Pacific Partnership. That agreement allowed a small percentage of U.S. imports into Canada before President Trump decided to end it.

In April, 68 members of Congress sent a letter to U.S. Trade Representative Ambassador Robert Lighthizer regarding NAFTA negotiations. The members of Congress urged an end to Canada’s pricing program and dairy tariffs, which impose a duty of nearly 300 percent.

Be Like Canada?

But the view from Canada is different. Dairy Farms of Ontario CEO Graham Lloyd said Canada’s pricing schemes are targeted at the domestic market.

“The fear or concerns that the U.S. seem to have with Class 7 is that we are going to be competitive in the world market,” Lloyd said. “But what needs to be understood is we actually don’t issue milk production for export purposes.”

Beyond just defending the Canadian system, Lloyd recommends that the U.S. should give it a try.

“From a Canadian perspective there is also a lot of sympathy for U.S. farmers,” he said. Lloyd said Canadian farmers once had the same struggles U.S. dairy farmers face now, before the country moved to its quota-based system.

“Farmers didn’t know where their markets were, they were having direct deals with processors,” he said. “Milk was getting dumped, there were no production controls and farmers were going bankrupt because they had no certainty of any market.”

Lloyd said that was all fixed by a supply management system based on three tiers: production control, pricing, and import control. Now, prices are constant and stable allowing processors greater predictability, albeit at lower margins.

“That allows for greater planning for them and that’s where you can maintain higher returns,” Lloyd said.

The idea has appeal among some farm advocates in the U.S. who argue that emulating the Canadians holds more promise that blaming them.

“Dismantling a system that is working in Canada so that they are more available to soak up our excess product … would not fix what is wrong here,” said Patty Lovera, policy director for the left-leaning advocacy group Food & Water Watch, which has worked to protect smaller farms.

Food & Water Watch warns that the small to midsize operations are being “squeezed out by the consolidation of industrial mega-dairies that now dominate milk production.”

Lovera cautioned against a “race to the bottom” result if the U.S. simply insists that Canada eliminate its own price and production controls.

“It would take other farmers who are doing well down to where farmers are here,” she said. “Which is what we get a lot of in our trade negotiations.”

In April, the same month that some lawmakers were urging a “get tough” approach to trade talks with Canada, a group of small farm advocates sent a letter of their own to Congressional leaders and Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue. In it, the National Family Farm Coalition, along with more than 50 family farm, labor and consumer organizations urged immediate action on the dairy crisis by adopting a system like Canada’s.

The groups said the best changes could come by implementing proposals suggested in the Federal Milk Marketing Improvement Act of 2011, introduced by Pennsylvania Democratic Senator Bob Casey.

Wisconsin organic dairy farmer Jim Goodman heads the National Family Farm Coalition. He said a supply management system has worked for Canada for more than 50 years and it will work in the U.S.

“Because the government doesn’t run it,” Goodman said. “They don’t have to be worried about providing subsidies for producers when prices get low because of all we’re supplied because that doesn’t happen.”

University of Wisconsin Director of Dairy Policy Analysis Mark Stephenson argues that there are lots of farmers who benefit from the current U.S. dairy system.

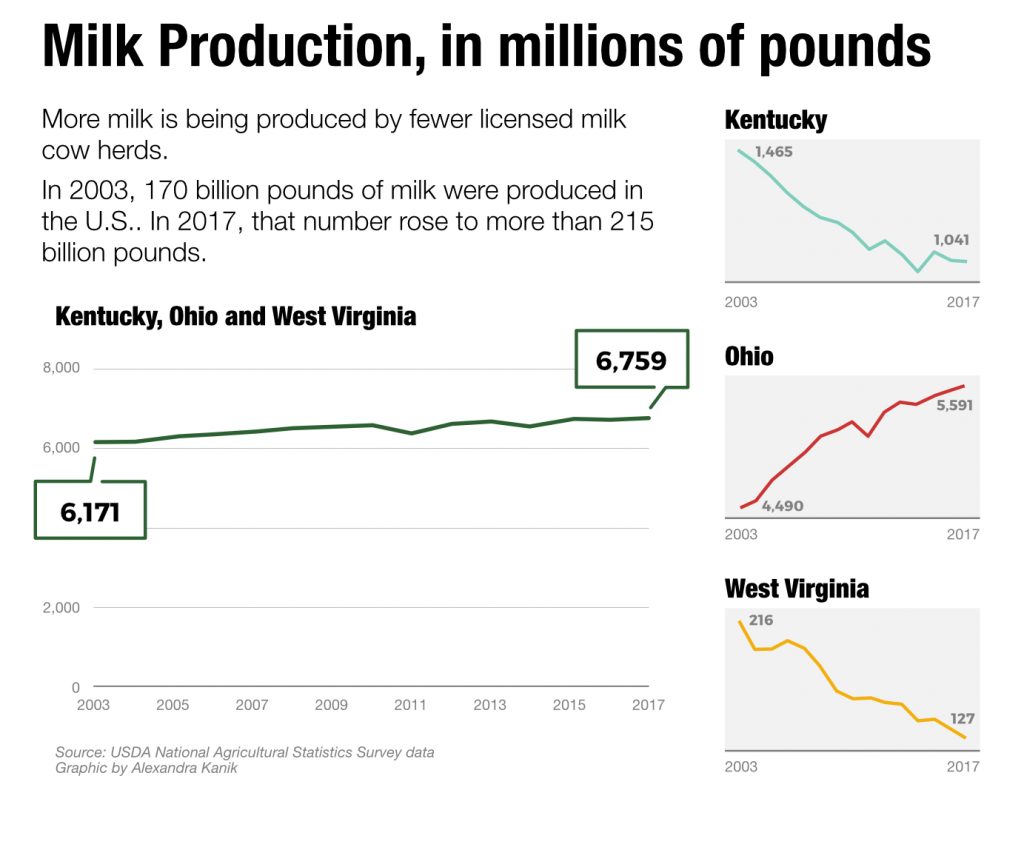

“We’ve had a number of people that, I think, would say the industry has done very well,” he said. “The evidence of that is that we’re producing more milk than ever before. We’re selling it at very reasonable prices to consumers both domestically and abroad.”

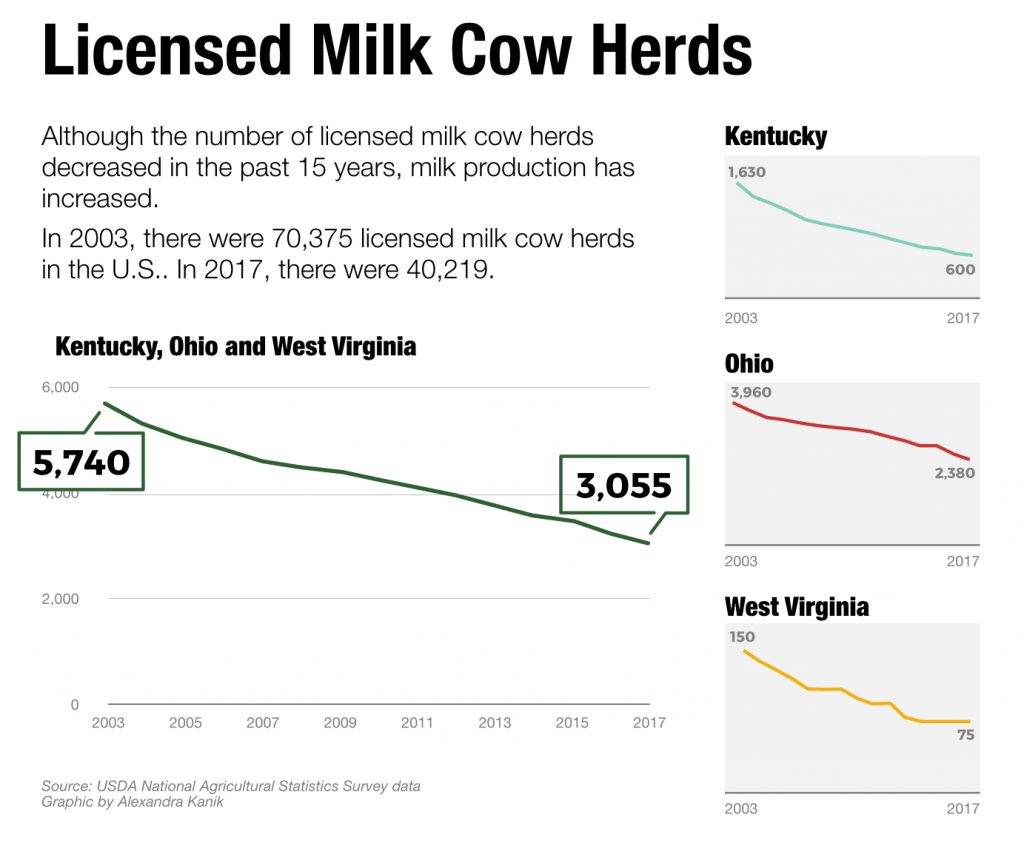

Those who tend to say the industry is doing well typically have much larger farms. At one time, Stephenson said, the U.S. had 6 million dairy farms. Today, there are fewer than 40,000.

“We’ve had a lot of discussion about how big should farms be, what right do they have to become a certain size,” Stephenson said.

“I’ve also heard a number of times that ‘bigger is better,’ and I don’t believe that at all,” he said. “What I think we see is that better is better. And if you are a better cow manager and a better people manager and a better financial manager, then you have better financial outcomes.”

According to the USDA cost is a driving force behind structural change. The largest farms earn substantially higher net returns and they have strong incentives to expand.

Slim Choices

National Family Farm Coalition advocates argue that Congress has a duty to protect family farms, and they point to law that states the “clear Congressional support for the continued existence of family farmers, including dairy operations.”

Back in LaRue County, Gary Rock said he likes Canada’s system but he doesn’t know if the rest of America would feel the same.

“You have to realize that our choices are very slim at this point,” he said, adding that the outcome would have effects far beyond farms like his. “What small dairymen are facing, it’s what we once knew as rural America,” Rock said, “trying to survive in an industry that is continually telling you, you have to become larger to survive.”