News

As Secret Money Surges In Elections, The FEC Considers A Small Step For Transparency

By: Peter Overby | NPR

Posted on:

When it comes to transparency for political money — who gave, how much, how it was spent — there are three buckets: fully disclosed, partly disclosed and not disclosed at all.

Long-standing law requires candidate campaigns and party committees to report their finances regularly. But among outside groups — political action committees, superPACs and nonprofit groups — nearly half the money spent so far in the midterm elections was either never disclosed or only partially disclosed.

Here’s what’s going on.

A new trend since 2016

In that cycle, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics, 72 percent of spending by outside groups not affiliated with a candidate or political party committee was fully disclosed. So far this cycle, it’s dropped to 52 percent, a level last seen when (non-disclosing) conservative nonprofit groups were trying to make Barack Obama a one-term president.

The Federal Election Commission is working on one part of this

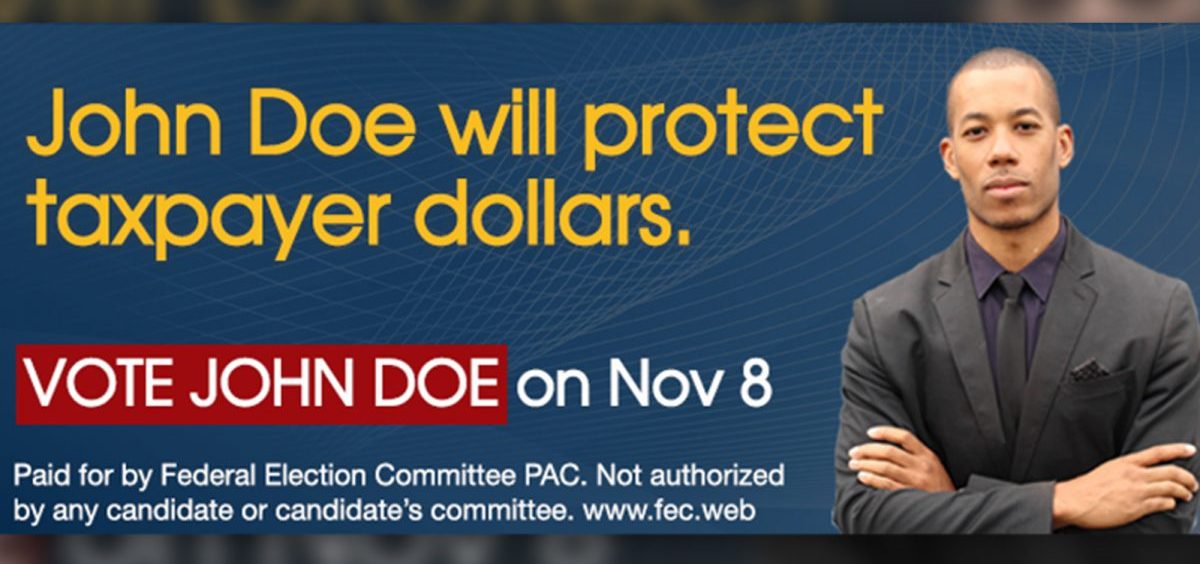

The commission, after months of urging by Democratic Vice Chair Ellen Weintraub, wants to develop a transparency rule for political groups that advertise online. The rule would mandate “paid for by” disclaimers, like the ones long required for political ads in broadcast and print media. But the rule would apply only to the relatively narrow category of “express advocacy” ads, which explicitly support or oppose a candidate.

The FEC held two days of hearings this week. The discussion leaned toward the technical: font sizes, pixel counts and disclaimer-to-message ratios. The commission last tried to tackle the disclaimer issue in 2006, before concluding the internet was evolving so fast, it didn’t make sense to set standards.

Commission Chair Caroline Hunter, a Republican, struck a more cautious note: “I know we all share the desire to try to come up with a rule in this case, and I know we’ll work hard together to try to do so.”

Russian interference in 2016 a driving force

Last month, USA Today analyzed some 3,500 Facebook ads from the Internet Research Agency, a Russian entity that was active in the efforts to sway the presidential contest. The newspaper found that more ads dealt with race issues than with the presidential candidates, and only about 100 ads fit the “express advocacy” category that the FEC would regulate.

A disclaimer skeptic, legal director Allen Dickerson of the conservative Institute for Free Speech, told the commission that if its proposed rule had existed in 2016, the effect would have been minimal. “It would have added a disclaimer to some set — some subset — of those 100 ads worth perhaps a few thousand dollars,” he said.

The Internet Research Agency, two other companies and 13 individuals were indicted last February in special counsel Robert Mueller’s probe of Russian interference in the election.

Supreme Court fight will drive a new wave of undisclosed spending

Nonprofit groups on the right and left are expected to pour millions of dollars into the confirmation battle for President Trump’s upcoming Supreme Court nominee. After Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement Wednesday, the nonprofit Judicial Crisis Network promptly posted a 30-second ad on its website to start building grassroots support for the as-yet-unnamed nominee. JCN could end up spending at least $10 million, its announced budget last year to confirm Trump’s first nominee, Justice Neil Gorsuch.

More broadly, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., said it’s become easier for big donors to avoid disclosure. “But that’s not a constitutional problem,” he said. “That’s a problem of political leverage and congressional spinelessness. And that can be corrected by pressure from the American people.”

He cited a recent poll, commissioned by groups led by former president George W. Bush and former vice president Joe Biden, that ranked “big money in politics” as one of two issues that most concern Americans about their democracy. The other was racism and discrimination.

Whitehouse is the lead Senate sponsor of the DISCLOSE Act, one of several reform bills that congressional Democrats are preparing to rein in the secret money and tighten other gaps in campaign finance law. They aim to have the legislation ready for action after the midterm elections, when they hope to win a majority in at least one chamber of Congress.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))