Scioto County waits for a new opioid settlement deal with Cardinal Health, McKesson and AmerisourceBergen

By: Caleb McCleskey

Posted on:

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB) – Two years ago, Ohio officials announced they had negotiated a multimillion dollar settlement with major drug distributors, money intended to help the state address the devastation brought by the opioid crisis.

“This is a historic day for Ohio,” Dave Yost, the state’s attorney general, said at the time. “We have $800 million coming to Ohio to fix this mess.”

But officials in Scioto County, which has suffered more from the mess Yost was referring to than perhaps any other county in Ohio, rejected the settlement, or at least their share of it, which they considered an insult.

The county, located in the heart of the state’s rural Appalachian region, is now pursuing its own case against the “Big Three” opioid distributors: Cardinal Health, McKesson and AmerisourceBergen.

Shane Tieman, Scioto County’s prosecutor, said the county’s share wasn’t near enough given what the county has dealt with from the opioid crisis.

“The thoughts of the commissioners were the amount of harm basically that we’ve received from this opioid pandemic, how much it has affected everyone, the overdose rates we’ve had in Scioto County, the rising crime and violent crime that we’ve seen – they didn’t feel out of principle that that was enough. They felt that it was blood money for our pain and suffering,” Tieman said.

Ohio has well over $1 billion in opioid settlement funds to distribute across the state resulting from lawsuits brought against multiple drug makers, distributors and pharmacies, including Johnson and Johnson, CVS and Walgreens. But southeast Ohio, one of the hardest hit regions in the state, will be receiving a relatively small portion of these funds.

The amounts some cities and counties in the region are receiving are so small that local officials don’t know what to do with the money and are just holding onto it for now.

Scioto County in particular became an epicenter of the opioid epidemic, Tieman said. “It hit us a lot earlier than it hit other areas partly because of the Appalachian culture we have. We’ve been dealing with this significantly longer than other places.”

“The extent of the damages in this county are astronomical and all you have to do is drive down the street and you see it to this day,” said Maggie Miller, a Scioto County assistant prosecutor in the civil division. “Scioto County is somewhat of a different beast compared to the rest of Ohio because it’s dreamland … that we are literally getting thousands of pills for every man, woman and child.”

Scioto was among the many cities and counties throughout the United States that filed lawsuits against the Big Three distributors. Those lawsuits were consolidated into essentially one big case before the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Ohio. Ohio ended up negotiating its own settlement in the case.

Because Scioto rejected the settlement, it’s now waiting for the judge in the Northern District to remand the case to Ohio’s Southern District so the county can move ahead on its own and either take the companies to trial or try to negotiate its own settlement.

The city of Portsmouth, the county seat in Scioto, decided to accept its share of the opioid funds, even with the county opting out of the Big Three settlement. Sean Dunne, the mayor of Portsmouth, said this was the toughest decision he ever made.

“The context was we would be advised by our city solicitor on legal matters and this was a legal settlement, and it was advised we should be a part of this settlement, to accept it,” Dunne said. “I understand where he’s coming from, however I think it’s insulting to get what we got.”

Portsmouth has received about $40,000 so far in opioid relief money, Dunne said. “I am still of the opinion that areas such as ours are continuing to be ignored to address the issue.”

The settlement funds are supposed to be used to support prevention, treatment and recovery programs and decrease the supply of illicit opioids.

Under the terms of the Big Three settlement, the funds are being distributed in three ways. Thirty percent of the money is going directly to local governments in annual disbursements over 18 years. The first two disbursements have already been made. The OneOhio Recovery Foundation, which was created as part of the settlement agreement, will distribute 55 percent of the funds through grants. The remaining 15 percent of the money is going to the state.

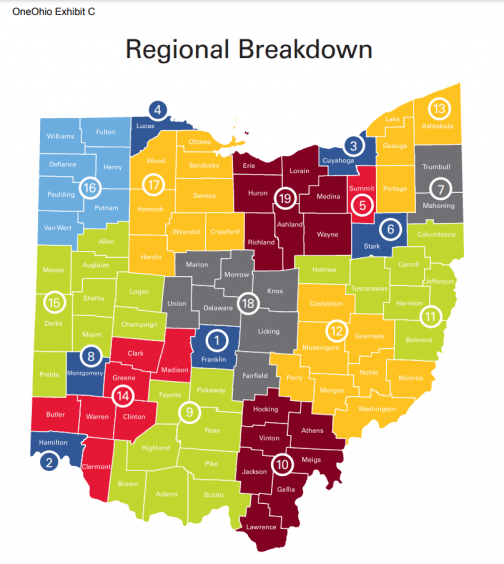

OneOhio has not distributed any money yet. It’s spent the past year getting organized. For the grants it will be awarding, the state’s counties have been grouped into 19 regions. Each region will be eligible for a fixed percentage of the funds.

For example, Region 10, which includes Athens, Hocking, Vinton, Meigs, Jackson, Gallia and Lawrence counties, is eligible for about 2.5 percent of the funds. That works out to a little less than four-tenths of a percent per county. Region 9, which includes Scioto County and seven others, is eligible for about 4.9 percent, or roughly six-tenths of a percent per county.

The reason those counties are getting much larger shares of the funds relative to the counties in southeast Ohio is simply because they are larger. The formula used to determine the share for each region considers three factors: the number of people suffering from opioid use disorder in a county, the number of opioid overdose deaths in a county, and the amount of opioids distributed in the county that produced a negative outcome.

These numbers are going to be larger the more populous the county is. But this isn’t the same as measuring the impact of the opioid crisis on a county relative to its size, which requires looking at these factors not just in terms of sheer numbers but on a per capita basis.

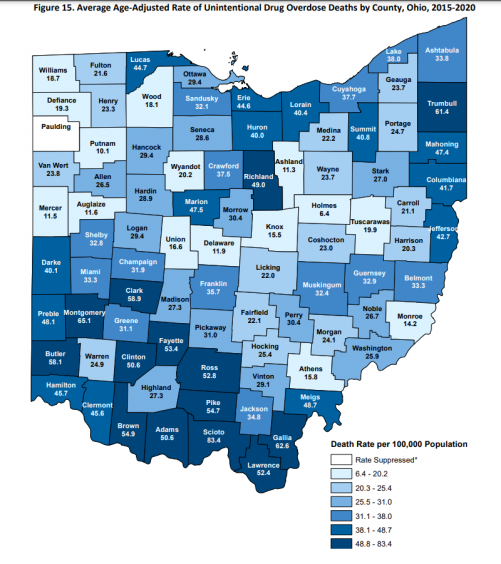

For example, from 2015 to 2020, the number of unintentional overdose deaths per 100,000 population in Franklin County was 35.7, according to state data. In Hamilton County it was 45.7.

The number for Scioto County was 83.4, by far the highest in the state.

OneOhio hopes to begin accepting grant applications in the fall and to start awarding the first round of grants next spring.

The grant funds can be used by organizations, boards, health departments and other groups that would create new programs to help with substance use prevention, treatment and recovery. Each region will have a process for reviewing applications and will then make recommendations to OneOhio on which applications to approve.

Given how small the regional shares are in southeast Ohio, some groups may be reluctant to apply for funds if it puts them in direct competition with other groups in the region and may be looking for a more regional approach.

Rebecca Robison-Miller, chair of Athens HOPE, said her organization will apply for the funds only when other organizations are on board with a program. “Unless our community and our members are saying we really need this project and the OneOhio funds can pay for it, then that’s the time we would consider applying for it,” she said.

Under language tucked into the state’s budget bill that was signed earlier this month, OneOhio is not a public organization and therefore not subject to the state’s public meetings and records laws. That language effectively overturned an Ohio Supreme Court decision in May that said the organization is a public body.

A spokesperson for OneOhio said that meetings of its grant committee, which will review grant applications and decide which ones to fund, will be open to the public, as are all of the organization’s meetings.

The 30 percent of the settlement funds being distributed directly to local governments is also based on the formula OneOhio is using, which was defined under the settlement agreement.

Under this formula, Athens County received $39,952 for its first-year payment and $41,987 for its second, the city of Athens received $6,057 for its first payment $6,365 for its second, and Portsmouth received $19,304 for its first payment and $20,287 for its second.

Columbus, meanwhile, received $348,798 for its first payment and $366,570 for its second.

The annual amounts coming to local governments in southeast Ohio are small enough that some officials said they’re saving the money up over a period of years until there’s enough to do something meaningful. Other officials suggested it may be best if local governments tried to pool their money and do something on a regional level.

Jessica Dicken, a Hocking County commissioner, said the county is saving its funds, but has a program in mind that it could spend the money on. “We need a program that can help felons get back into the workforce and not just find a job, but find a career,” she said. “So our goal would be to see that used in a program that helps with job interview skills and also though going into businesses and trying to convince them that these people still need a change.”

Some people working on the front lines of the opioid epidemic in southeast Ohio are unsure how much of an impact the funds can have given the amounts.

Robin Harris, executive director of the Gallia-Jackson-Meigs Alcohol, Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Board, said the funds won’t scratch the surface when it comes to the damage done to the region.

“When we talk about the impact of the opioid crisis in Gallia County, it’s so far reaching,” she said. “It has created a crisis within law enforcement, it’s created overcrowding in the jails, it has created a homelessness problem in the community.”

For Dunne, the Portsmouth mayor, the settlement money is yet another chapter in southeast Ohio’s long story of being overlooked.

“It’ll remind us that our area is valued less than other areas,” he said. “And then after that hopefully the funds will at least have some impact and that we were able to make the best use of an insultingly low amount of money.”