Culture

Recognizing the Photographic Legacy of an Influential Bobcat: Chuck Stewart

By: Emily Votaw

Posted on:

You may not know it, but you’re likely already familiar with the photographic work of Ohio University alumnus Chuck Stewart (BFA ’49).

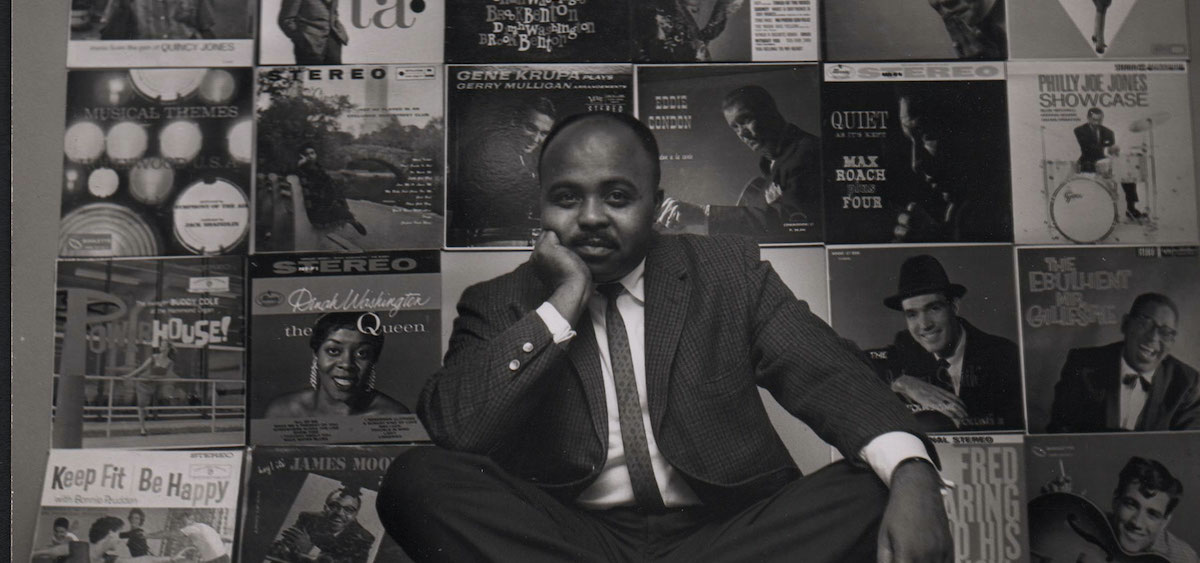

Over the course of his 70-year career, Stewart’s eye framed and photographed images iconic to the American shared subconscious, from a pensive John Coltrane during his 1964 A Love Supreme recording sessions to images of the U.S. Military’s atomic bomb tests of the early ‘50s. His images adorn over 2,000 album covers, and have been featured in documentaries about the likes of James Brown, John Coltrane, and Maya Angelou.

Stewart also professionally photographed Thelonious Monk, Led Zeppelin, Janis Joplin, The Beatles, Albert Einstein, Jackie Robinson, and Mike Tyson (just to name a few!) throughout his career.

Chuck worked harder, smarter, and created work more beautiful than that of his white peers all while working in a country that would only officially outlaw discrimination based on race years after Chuck graduated from Ohio University.

Chuck Stewart passed away at the age of 89 in 2017. And as it turns out, even some of Chuck’s closest family were unaware of his enormous professional feats. This is quickly changing thanks to one woman: Chuck’s daughter-in-law and the representative of his estate: Kim Stewart.

“Chuck had so much history,” said Kim, who was married to Chuck’s son for more than 15 years before she finally learned about her father-in-law’s impressive past. When Chuck was about 80 years old, he spent four weeks in a rehabilitation center following a coronary angioplasty, and over the course of those four weeks, Kim would visit him every day.

“I would sit there and talk to him, and then he starts talking about photographing Albert Einstein!” said Kim. “I was like — ‘who are you?'”

Chuck discovered his talents when he was only 13 years old. Armed with an Eastman Kodak brownie camera his mother had given him, Chuck’s first photos were of internationally renowned contralto Marian Anderson when the singer visited Chuck’s middle school in Tucson, AZ. Anderson was the first African American to perform at the Metropolitan Opera, and only a few years before Chuck would photograph her, she famously performed for a crowd of 75,000 from the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. after the Daughters of the Revolution didn’t allow her to perform for an integrated audience in a venue they owned.

“Everybody wanted one of Chuck’s photos of Marian Anderson, and he ended up making about two dollars on the photos, when his allowance was only 25 cents a week!” said Kim. “That’s when he made a decision that photography was for him, 13 years old in middle school.”

Chuck honed his skills throughout high school, and when he decided to pursue a Bachelor’s of Fine Arts in photography, he would find that the only collegiate level degree granting photography program in the country that would accept black students was Ohio University — nearly 2,000 miles from his hometown of Tucson, AZ.

“At Ohio University, Chuck did his thing. He furthered his interest in photography, managed the school’s dark room, and was in charge of two yearbooks,” said Kim.

Although Chuck’s formal photographic training at Ohio University would serve him well throughout his professional career, perhaps one of the most important portions of his time at Ohio University was his befriending of fellow aspiring photographer Herman Leonard. Leonard would go on to be recognized as one of the most important photographers of the New York City jazz scene throughout the ’40s and ’50s, and in 2009, Ohio University granted Leonard an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts.

Leonard and Chuck would develop a tight, lifelong friendship.

After graduating from Ohio University, Chuck would briefly serve in the military, taking the aforementioned photos of the atomic bomb tests conducted by the U.S. military in the ’50s. Once Chuck finished his military service, he took Leonard up on his offer to share Leonard’s New York City photography studio.

It was this deep bond with Leonard that allowed Chuck to gain access to racially segregated New York City clubs; Stewart playing the role of apprentice to Leonard. Once inside the clubs, it was Stewart’s unique abilities that landed him opportunities to photograph some of the most significant artists of his time, often being asked to do so personally by the artists in question because they liked Chuck’s photos so much.

“Chuck had access to the clubs, and then he had access to the artists. Matter of fact, it was at Birdland where he was on assignment to take pictures of Duke Ellington, and Count Basie was there and said, ‘you’re here every night and you never take pictures of me!'” said Kim. “So, from that point on, Chuck made sure he he took pictures of Count Basie as well.”

These personal connections were essential, as at the time, the media industry as a whole often refused to hire or work with black photographers. Even amidst this, the quality of Chuck’s work embedded him in the burgeoning world of jazz – an art form whose rise into the mainstream American cultural consciousness coincided with the popularization of the long playing album.

Many of Chuck’s most iconic works would adorn jazz albums and liner notes; his pictures of Art Blakey, Elvin Jones, Thelonious Monk, and many others providing devotees of the genre a rare glimpse into a world from which the music they loved sprang.

Although Chuck would form friendships with the likes of Quincy Jones and Max Roach (becoming Roach’s personal photographer for a time), once Chuck moved to Teaneck, NJ in 1965 with his wife and three children, few of his family members or close acquaintances had any clue as to the caliber of work Chuck had created.

“I think Chuck always looked as what he did as a job. He and his wife would double date with other couples, and the conversation would turn to music and so on and so forth. And the other couple would just happen to mention what they liked jazz. Then a couple days later, there would be an envelope in their mailbox or on their doorstep of photos Chuck had taken of the artists they had mentioned,” said Kim. “He just loved taking pictures of his subjects. He was caring about it, but it was a job. It was to pay the bills. He had a wife, three children, a mother-in-law, and a dog. He was trying to provide for his family. But you could tell he loved what he did. He loved the travel of it. He loved his subjects. When it came to jazz, he definitely loved the music.”

Starting in the final years of Chuck’s life, Kim set out on her mission to get Chuck the recognition and financial compensation he and his family deserved.

In 2014, Chuck and Kim donated 25 images to the Smithsonian to contribute to the museum’s celebration marking the 50th anniversary of the release of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme; the recording of which Chuck had photographed half a century earlier. Subsequently, Chuck and his family were invited to a ceremony at the Smithsonian thanking them for their contributions. The ceremony was intended to also thank Coltrane’s son, Ravi, who donated one of his father’s saxophones to the Smithsonian – but that morning Ravi was not feeling well, so the focus of the ceremony shifted entirely to Chuck.

“Even though John Coltrane’s name is big, Chuck’s name went out there simultaneously with John Coltrane’s, and news about this was in something like 24,000 different media outlets. And once AP picked it up, it just went all over the place, all over the world. There was a flash about this all over the globe!” said Kim. “So, I will say Chuck was celebrated.

Since his passing, Kim has worked to get her father-in-law’s work into the collections of various institutions. Currently, a portion of Chuck’s work is on display at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, OH in their “It’s All Been Said Before: Voices of Rage, Hope, and Empowerment” exhibition.

“God willing, I have another few more years to do this work, not that Chuck will be a household name by then. I’m laying the foundation because there’s a lot, there really is a lot. What he left us, it’s millions and millions of dollars worth of stuff,” said Kim. “I’ve already spent many years on this, but I don’t have 70 years to spend on somebody else’s life. I have a lot of passion and vision for this, and I think that’s why Chuck left all of this for me to do (…) because he knew I could do it.”